TORBJØRN RØDLAND & KRISTIAN SKYLSTAD

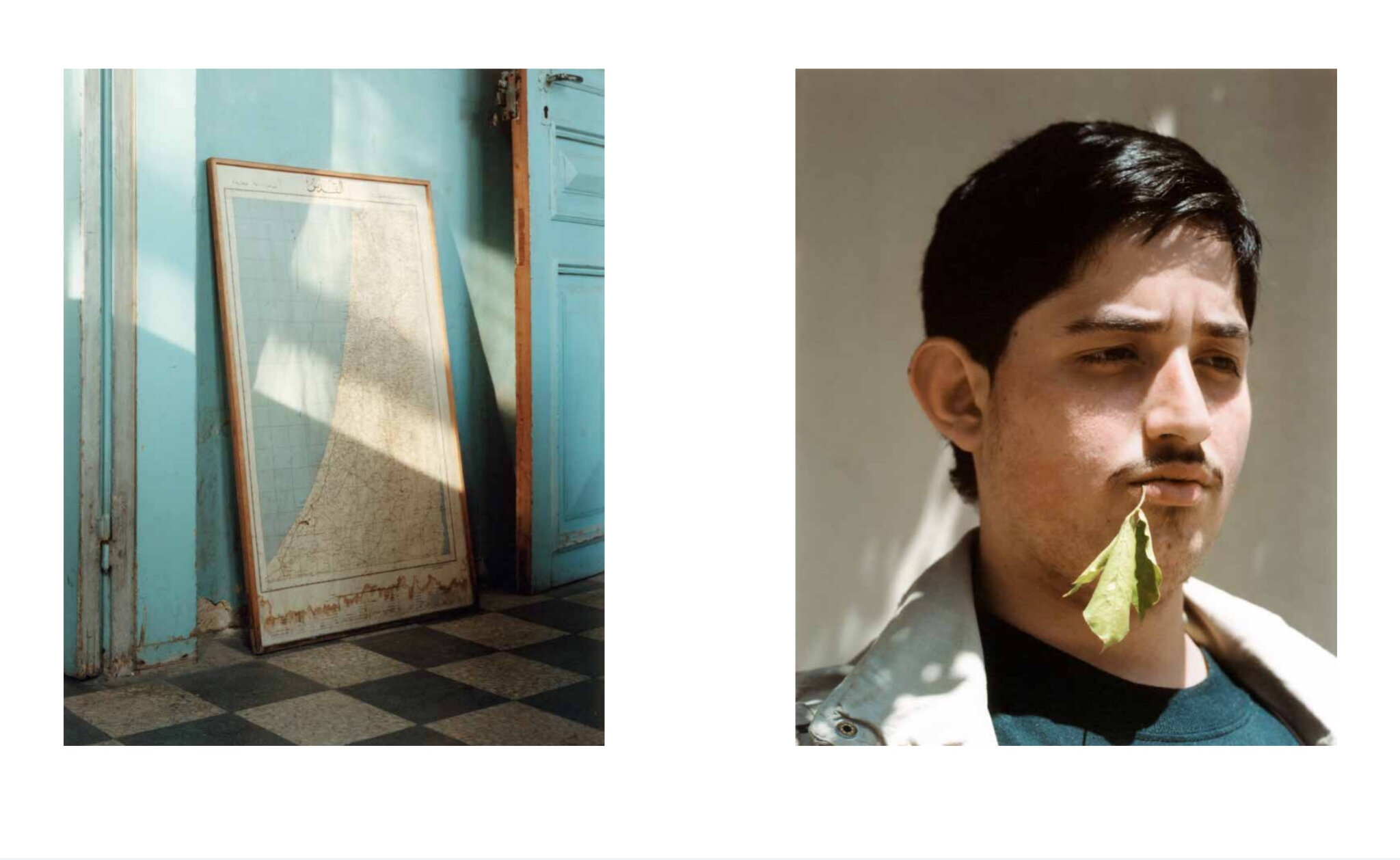

Torbjørn Rødland, Meganekko Moe, 2003-14, from Sasquatch Century at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter.

Kristian Skylstad Is your production affected by your biography?

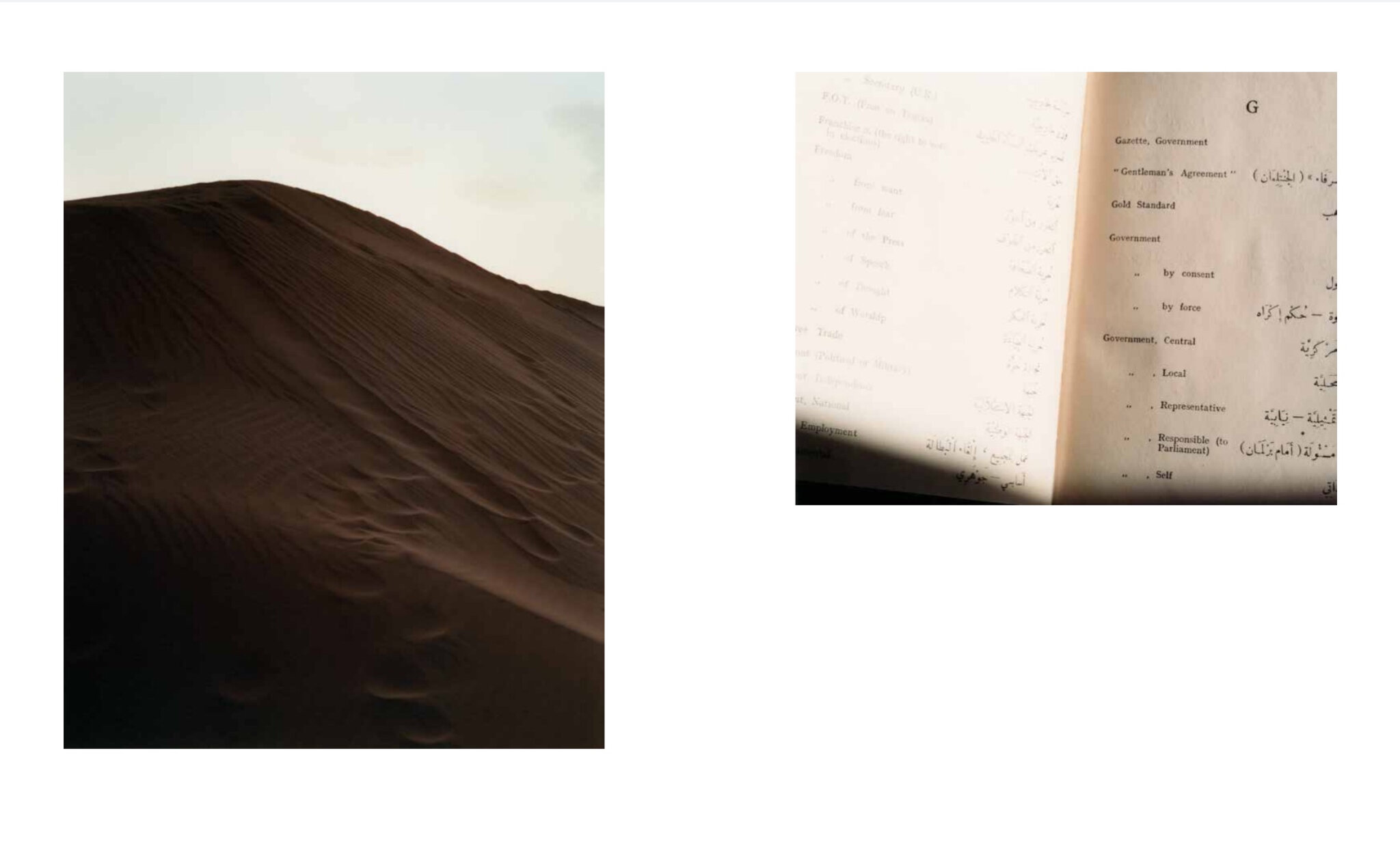

Torbjørn Rødland I believe art will always be affected by biography, not just for me but for everyone. Most artists tend to focus on other aspects, though. A photographer finds and places the camera in front of something, or something in front of the camera – a person, a site, an object. Sometimes I photograph objects I’ve travelled with for a while – it might be a leather strap from Tokyo or some stockings from Beijing. Even when certain elements aren’t from the place where the photograph is made, the local always bleeds into the picture somehow. If you compare my work to a photographic project based on the standards of reportage, the bleeding I’m dealing with is limited. My job is to externalise internal images, which are both personal and cultural. I’m actually keen on finding ways to deal with personal factors in art, especially since this was largely avoided by the previous generation of artists.

KS Unlike that of my generation, where the personal is inflated.

TR At the time when I defined my project, no one was talking positively about biography. If you know Jeff Wall’s story, you’ll find that the background for some of his pictures is almost soap opera-like, but he’s not comfortable sharing that, probably for good reason. The biographical reading has a tendency to overshadow other motivations. Most people still expect art to be a processing of personal experience, even though for a long time now postmodern artists have aspired to a role as social critics of a culture not centred around a specific individual. I accept that my pictures operate on different levels that are both interesting and irritating, depending on where you stand. These different levels are integrated or in balance.

KS The photographic, art and poetry – in contradiction to other forms of culture that point at something specific – tend to look for an eternal understanding, but that also means an eternal misunderstanding. Gauguin once said that the art was inside his head and nowhere else. Is your work a manifestation of your fantasies? You work with ideas, but your work isn’t conceptual.

TR An idea in itself has no value. The image is both result and starting point – it starts with an image that I don’t know how to deal with or to explain, and in the process of creating my version, I try to figure out why exactly it’s worth paying attention to. Creating the individual image is one thing, but how it fits into a format and inside a bigger group of pictures is essential. This process ends with an exhibition or a book, or both.

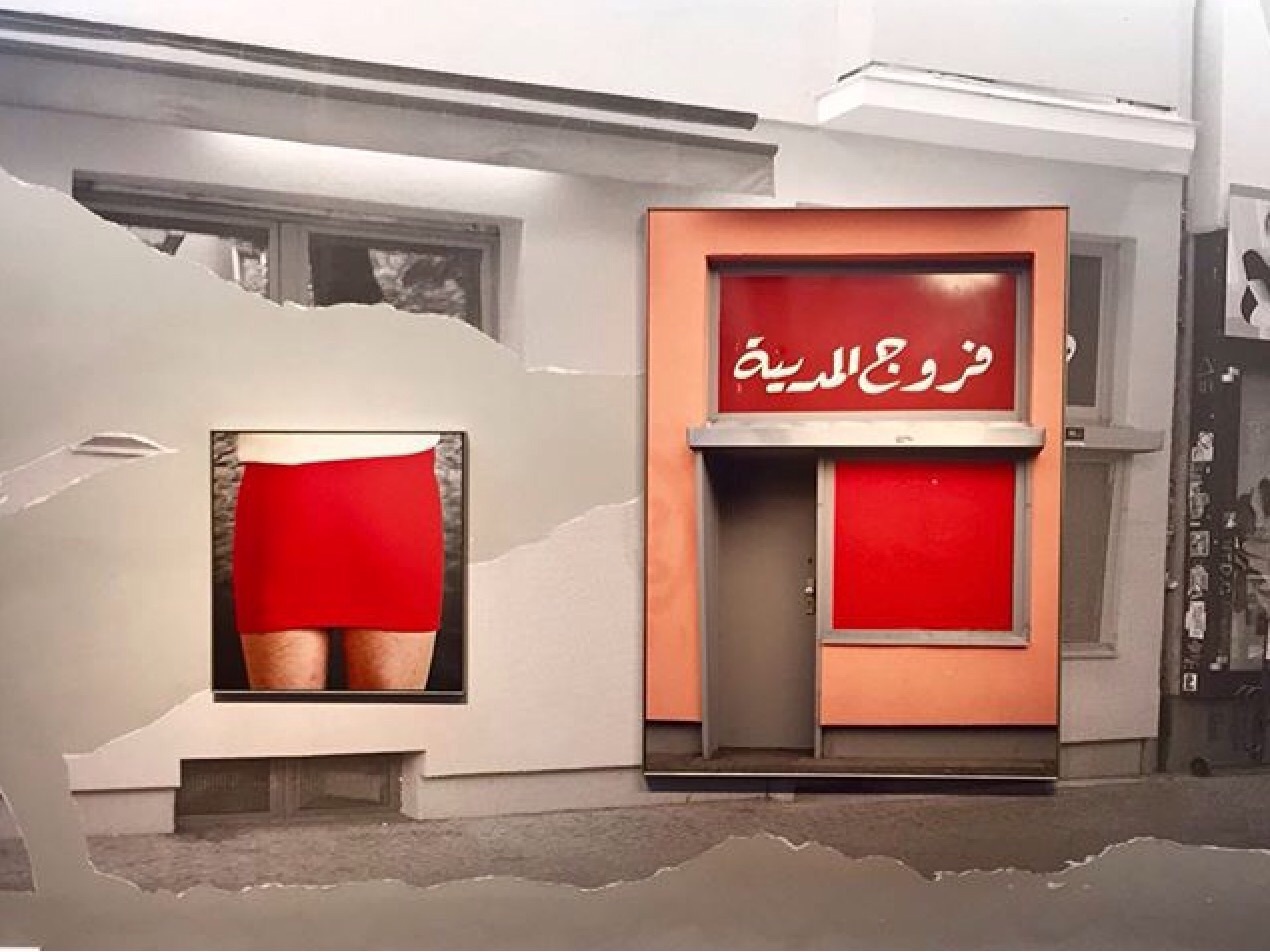

Torbjørn Rødland, Summer Scene, 2014, Courtesy of STANDARD (OSLO)

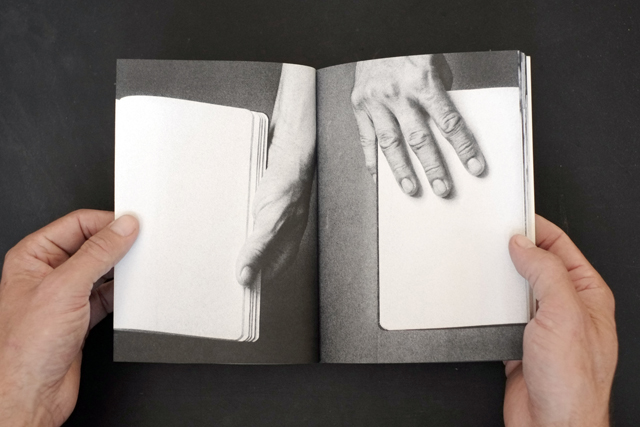

KS Which format has most importance? Do you compare their value? The book is eternal but the exhibition is fleeting.

TR When I was a student, the book was my main interest. Then I got pictures published in different contexts, and it always left me discontented. Mistakes were made, photographs were cropped and mislabelled – they didn’t look good most of the time. This made me gradually appreciate the exhibition, because there I was able to control the result. A dialogue in a room is very different from a book. They’re both interesting, but different. I started exhibiting internationally twenty years ago, ten years before I put my first real book together. I learned about how to exhibit photographs. The book format came in later and redefined the production. The images in I Want To Live Innocent from 2008 were created with a publication in mind. The book was the main framework and first context. Later, I would make exhibitions from more pointed selections. This was also the method for Vanilla Partner from 2012.

The book allows a broad production with many genres and image types coexisting. An exhibition holds a different tension, because you can see many more images at the same time. Some pictures that function in a book don’t work on a wall. You can compare it to playing live for many years as a musician, and then releasing an album. The benefit of the album is that it can be discovered and experienced whenever and wherever, while a concert has a very limited duration and extent.

KS Is your process intuitive or carefully planned?

TR What can potentially happen in front of and inside a camera is miraculous. I go for the photographic negative, which can’t be planned in detail. If I don’t succeed in creating a picture on my first attempt, making a new one is almost impossible. This has happened very rarely and only with pure still-life or object photographs. I believe I share this process with everyone who works intuitively: you have an inner picture of what can potentially be and this conception is essential for you to push the material or the situation beyond what’s ordinary and towards something indispensable. To get there you have to be open to what might potentially happen. I realise that the image I actually make is much more valuable than the one I planned to make. The final photograph has more precision, more individuality. Much of the joy in my working process comes from discovering qualities and symbols and consistencies in a completed body of work. I aspire for this to happen. I relinquish control, and then I react to whatever occurs. I’m not alone in this method. I do believe that both painters and writers work like this.

Torbjørn Rødland, ACV09, 2009, Courtesy of STANDARD (OSLO)

KS In your gallery shows you’ve often chosen a more eccentric and absurd selection of images than the work you’ve shown in institutions, even though it still has the same connotations. I’m specifically interested in the Andy Capp Variations, which in my eyes is an aesthetic exception. Where were you going with that series?

TR In retrospect I think the Andy Capp Variations, maybe more than anything else I’ve done, demonstrates the need to work through and go beyond postmodern appropriations by integrating qualities from classical art photography. The flat and mediated cartoon character is appropriated from a bar mirror photographed and combined with intimate everyday objects observed with an interest in personal association and light, surface, texture. I see an almost desperate need to reconcile different levels in one picture. As a viewer, you can choose to focus on the poetry of the familiar or you can miss these qualities because you’re provoked by the stupid Andy character, but the elements are there and in balance with each other. It’s pretty much the same balance as in my early photographs of myself as a long-haired art student with a plastic bag in the forest.

KS In your multiple exposures you’re exploring something more pictorial.

TR The multiple exposures show many parallels with what I tried to achieve with the use of a mirror in the Andy Capp Variations, but here it’s the result of two separate exposures on one photographic negative. I don’t know if it’s more or less pictorial. You could also see the double exposures as more in line with modernist photography and its critique of pictorialism. To me, they complicate the pictorial space in ways that are different from the single-view photographs that dominate my catalogue. Multiple exposures became another way of creating a fantastical pictorial space with basic photographic methods. I could have controlled it much better in Photoshop, but this is about losing control. I’m interested in the complexity of a picture. Here the layers are readable through the basic physics of analogue photography.

KS There are many markers in your early work referring to specifically Norwegian themes: heavy metal in the forest or nudists. As a Norwegian artist I find this liberating.

TR Yes, especially when I made portraits of Erik Bye, Maria Bonnevie and Titten Tei. The Black Metal musicians are all pretty much my age. It was important to me to look at how my project overlapped with and differed from theirs. Later, my focus expanded to include elements from American and Japanese image culture. On a trip to Japan in 2002 I discovered that the marginalised cuteness that came out of my 1990s production was mainstream in Japan. This discovery sent me back to Tokyo to talk to people and try to understand what the hell I was doing. The advanced Japanese image culture is very different from the Western one, partly because it developed outside of humanism. My belief is that many of the changes in mass culture in the United States and Europe after the internet have followed Japanese pop-culture: the acceptance of extreme cuteness and explicit eroticism are two examples. Japan has also developed a more advanced discourse around passion and strong feelings for fictional characters, for boys and girls, that you only get to know through visual media.

KS These kinds of cultures are more or less taboo in Scandinavia.

TR In Scandinavia we have strong ideas about how things should be. These basically Christian morals were continued and further developed in Western humanism. In Japanese pictorial culture, human nature is understood quite differently.

Torbjørn Rødland, Dancer, 2009-2012, from Sasquatch Century at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter

KS Photography has never been as powerful and popular as now. How does this affect you?

TR The idea of a reality dominated by pictures I know intimately from postmodern theories of the offline era, but there seems to be less shame in clichés now. It’s no longer problematic to explore experiences emulating banal photographs or movies. Quite the opposite. I always wanted my work to be more than self-conscious variations on worn-out cultural forms. The first photographs I did made me attempt other ones, which led to a couple of movies, which again led to quite different pictures, followed by a few books that led to some multiple exposures. I never had to stop and redefine this ongoing process because of Flickr, Instagram or Facebook. Changes in my work run alongside the development of these new social platforms. Dialogues do occur, since I reach for purely photographic qualities and a human appeal. I observe and I participate in the increased sharing of photographic material, but my project started rolling before the internet was fast enough for photography.

KS You staged some photographs before the internet that have qualities that are now a kind of norm on social media.

TR Something similar happened to major chunks of the photographic art I got to know in my twenties; it’s to do with teen image production. Memes are pure expressions of postmodern pluralism; the truth is not out there, memes say. Various contexts and surfaces reflect and distort each other, to everyone’s amusement. To me, this was a starting point. I tried to move on by no longer rejecting an inner life of emotions and contemplation, and by seeking contact with the juiciness of the real. On the internet you’ll find a lot of naïve photographs, a lot of cynical photographs, a lot of humorous visuals, but you’re not overwhelmed by this type of integrating project aspiring to be more inclusive than pluralism.

KS Do you deal with photography and art in the same way?

TR I see no reason for a division between the two. I process other forms of expression in the same way as photography. I have little sympathy for magazines and internet sites with separate sections for art and photography. If a sculptor hires a professional photographer to make a picture for him then it’s art, but if an artist manages the whole process herself, it’s photography. That’s what’s happening, and the medium of photography tends to gravitate towards contexts where luxury goods are promoted, especially in magazines. I call it a problem but the closeness to popular visual communication is also what makes art-as-photography so exciting and often so difficult to judge. Reading a photograph is now a very complex thing. This annoys a substantial number of people. Projects that stay within the overfamiliar zone of conceptual art are safe. Pure appropriation – to move a magazine page into the gallery space in order to study its form, its ethics and aesthetics – is a protected exercise. But this “critique” doesn’t challenge anyone anymore. Everyone is familiar with basic postmodern strategies. We understand an artist using photography. It’s more complicated to come to terms with the complexity in a photographer’s approach to a breathing world of beauty, life and consumption.

It’s sad that the art world didn’t learn more about photography in the short period when it dominated the scene. I see now how unable people are to evaluate the quality of a photograph. You could say that I advocate a rich photographic image that very often needs the context of art to stand out in a landscape of simplifying commercial structures. We just don’t seem to have a language for the kind of image that transcends these biased devices.

KS Do you have a language for it?

TR Well, we’re trying to create a language, to explain what happened and how we got here – not by rejecting conceptual art but by transcending it. If we want to redefine pictorialism, it can’t be pre-conceptual; it has to be trans-conceptual. We need more ambivalent categories, or categories that contain ambivalence.

KS You believe that it’s valid to channel these ideas through photography?

TR This isn’t something that I channel through photography. This is something photography channels through me.

KS I’ve never heard that one before. It reminds me of something Roberto Bolaño could or should have said about poetry.

TR I’m not sitting here with fancy ideas that I seek to spread using photography. I try to understand what I’m actually doing with this medium and why I return to certain kinds of pictures. I try to understand why and how they’re meaningful.

KS What’s the next step?

TR Oh, I just continue photographing. It’s a way to accept the passing of time – to realise I’ve made something I’m satisfied with. Often, when I see something that could become a picture I realise that a photograph I’ve already made is stronger than the one I could do there. Then I don’t have to pick up a big camera. In other words, I can imagine the project coming to an end. Maybe at some point there will be nothing left for me to do.

KS Have you ever considered quitting?

TR No.

KS You depend on it?

TR I’ve never thought of it like that. But I have nothing stronger or more meaningful, which may be a bit sad. Observer types often become photographers because they’re not so good at participating. Photography has fascinatingly enough become an entrance point for participation. If your photographic practice is oriented towards reportage you’ll end up searching and waiting for stuff to happen in front of the camera, but my approach is more active. I initiate a world that’s meaningful to me, as a picture but also as a place to live.

Torbjørn Rødland, The Measure, 2010

This text was first published in Objektiv #10.