DRAGANA VUJANOVIC & ANN-CHRISTIN BERTRAND

Hellen van Meene, Zonder titel, 2014

A conversation between Dragana Vujanovic, Chief Curator at Hasselblad Foundation, and Ann-Christin Bertrand, Curator at C/O Berlin Foundation.

Nina Strand Our current issue is inspired by the conference, Fast Forward – Women in Photography. First of all, do you have any thoughts on who you’d like to fast forward or rediscover?

Dragana Vujanovic The Norwegian photographers Berg & Høeg come to mind, whose private photographs from the end of the nineteenth century were discovered in the 1990s. The remarkable images show Marie Høeg exploring gender identities, with Bolette Berg behind the camera. The duo remains relatively unknown outside of Scandinavia. A few new prints are part of our collection and were recently included in the exhibition Framing Bodies. They drew a lot of attention from a wide audience. I’d also like to mention Erna Hasselblad, co-founder of the Hasselblad Foundation, a driving force in the Hasselblad company, but historically over-shadowed by her husband Victor. One of our ongoing projects is to highlight her position and draw more attention to her contributions.

Marie Høeg & Bolette Berg, Preus Museum

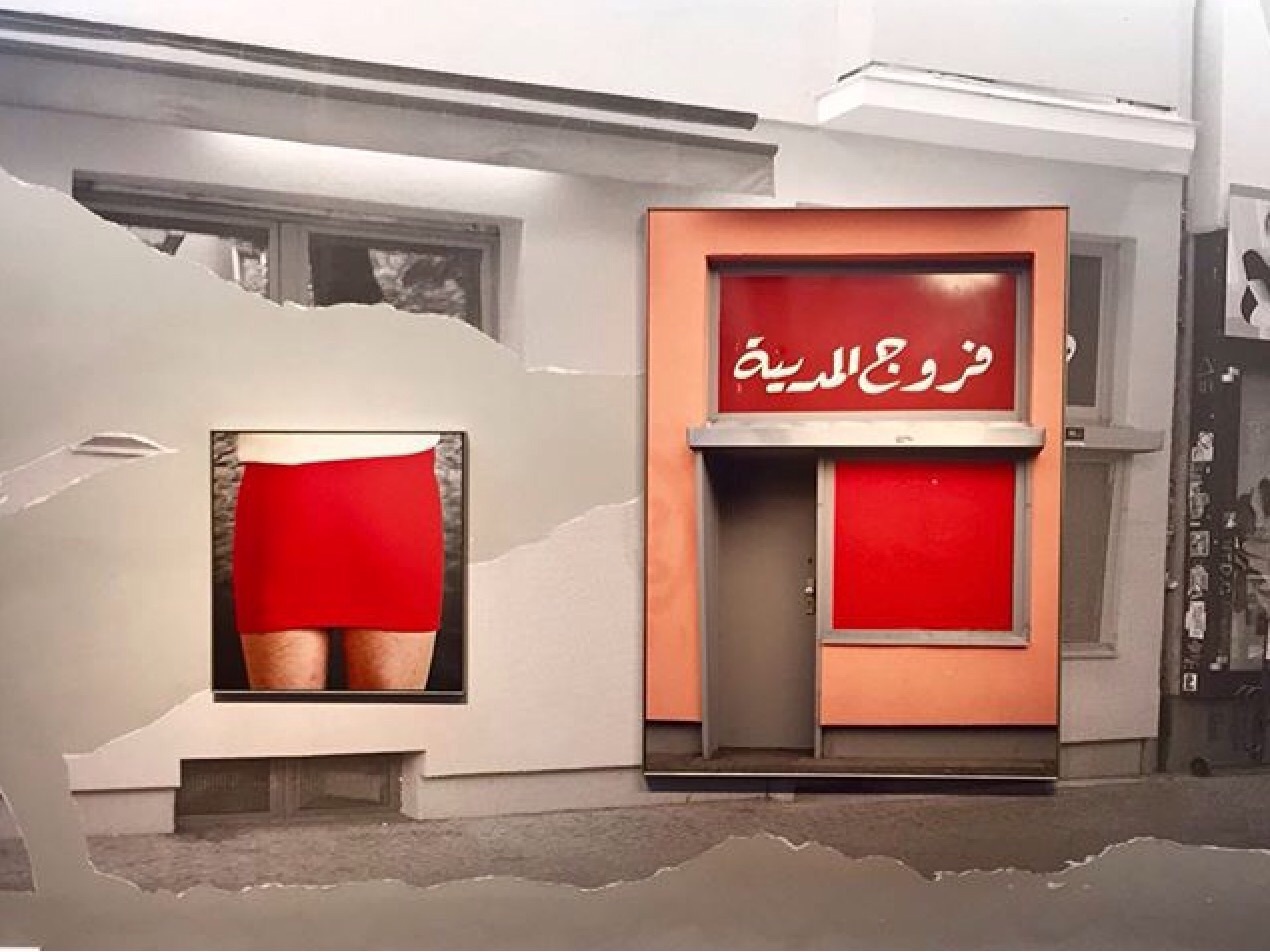

Ann-Christin Bertrand I’d like to fast forward in a more contemporary direction. I think it’s very interesting to see how digitalisation and the Internet have changed the way we contextualise photography. We’ve just presented the exhibition Marriage is a Lie/Fried Chicken by Victoria Binschtok at C/O Berlin. Since 2001, she’s been tracking the changes regarding our use, perception and distribution of photography in regard to the Internet in a very smart way. But if I look into the past, I’d fast forward the recently re-discovered photographer Lore Krüger, a former student of Florence Henri, whose work we presented at the beginning of this year. The exhibition A Suitcase Full of Pictures was a real discovery and had immense success, both in the media as well as for our audience.

Victoria Binschtok, Marriage is a lie / Fried Chicken, C/O Berlin

DV It’s important not only to bring forth photographers from the past, but also to think about representation in our work today. Being part of an institution, I feel a great responsibility to bear this in mind and evaluate our practice in terms of representation. One of the first things I did when I started working here five years ago was to look at the exhibition history and at the poor representation of women among Hasselblad award winners. Since 2010 we’ve organized fourteen solo shows with women, and eleven with men. In group shows we also strive to achieve a balance, if not 50/50, then at least 40/60.

ACB At C/O Berlin, however, we look at the quality of the work first, and only as a second step whether the work is done by a male or female artist. For us, quality is the most important argument.

DV The work always comes first, and in my opinion, quality isn’t compromised by taking equality into account. One doesn’t exclude the other.

ACB I fully agree. Maybe the best way to describe it is that we take into account ‘human kind’ in general, as well as the quality of his or her artistic work, instead of thinking in terms of gender proportions. When speaking about woman in photography, I think it’s very important to consider social history and the changing circumstances for women within society. Today, however, we have new ways of distributing our work: we can self-publish it or distribute it online. The aspect of sharing, exchanging with each other, working together has become increasingly important. These changing circumstances today make it easier for women. But this is more a social-political aspect than a purely artistic one.

NS A few years ago the Norwegian singer Susanne Sundfør protested while accepting an award for best female singer: ‘I’m a singer, period’, she said on stage. Does anyone really want to be a female photographer/curator?

DV It depends on the context. I think it’s important to be referenced as a female curator in a context where it has political and empowering value. After all, that’s why I’m part of this interview. There’s a difference between shedding light on (overlooked) experiences and portraying stereotypes. I don’t explicitly describe female photographers as women unless it’s a relevant factor. For instance, Ishiuchi Miyako is so far one of only seven women to receive the Hasselblad Award, out of 34 award winners. It was important for us as an institution to highlight this imbalance and also to stress Ishiuchi’s unique position within the male-dominated Japanese photography scene. Another example is Tuija Lindström, a Finnish-Swedish photographer whose work we exhibited a few years ago. During the 1990s she was the first female professor of photography in Sweden, also breaking a male-dominated field and introducing feminist perspectives and a more theoretical and critical approach to photography. These were relevant things to include in our information about her and her role within Swedish photography. In my opinion, not talking about gender when it is significant is maintaining gender-blindness, much like a disregard of racial structural discrimination is maintaining colour-blindness.

Ishiuchi Miyako, ひろしま Hiroshima #9, 2007, © Ishiuchi Miyako

ACB I absolutely agree with Dragana. Nevertheless, let me point out an aspect that came up at the Tate symposium in 2014: one woman sitting in the audience said she didn’t want to be brought into the context of ‘women in photography’, since she was afraid belonging to a ‘minority’ would make her work less valuable. I understand her worries. Also, why does it have to be only women in a symposium about women in photography? Why not open up the discussion to male participants? We should continue to talk about it, in smaller groups, everywhere and with everybody, not only once a year and not only with women.

DV Of course, we should highlight the work first and foremost, but being aware of the structural discrimination facing certain groups, and trying to reflect the field of photography in a more balanced way is crucial. Not considering gender and race is simply not an option today, especially not from an institutional point of view. In my experience, this awareness doesn’t somehow lead to diminished value – quite the opposite. It’s a problem that art institutions are predominantly male, white and straight.

NS I’ve just read Siri Hustvedt’s The Blazing World, in which her main character, artist Harriet Burden, let’s three different male artists exhibit her art to see if the work will read differently. I loved the book, and wondered if it rings true for other people?

ACB Siri Hustvedt is one of my favorite authors and I read the book this summer. I really liked it for its intelligence. It raises very important questions about how we look at art, how we perceive it. And it criticises the powerful influence of the art market or art world on our perception of an artwork. It also questions very important gender aspects – the fact that there are still more male than female players in the field, and at the same time is a brilliant observation of our art-market strategies and functionalities. It’s a very smart contribution to gender and art discussions and I just hope that it will ring true for far more people.

NS While working on this issue it’s become clear to me how many institutions are led by men. I’m curious to hear your thoughts on this.

ACB This is another important question regarding the gender discussion. Indeed, when it comes to leadership positions within the art world, it’s striking that – apart from a few female curators and directors - women are rarely in the higher positions, at least not in Germany. And in the photography world, this situation might even be a bit better than in the other media, as photography is a quite open and democratic medium. Here, there’s surely still a lot to do. What would you say about Scandinavia? Is it different there?

DV Not really. The art world is dominated by women in all positions except leadership, which is the case in many professional fields. And with few women and, more importantly, with few feminists in leading positions, change happens slowly. We try to keep this in mind when we put together the Hasselblad award committees. Small decision-making groups like these need to consist of people who are aware of the issues of representation.

Helen van Meene, Zonder titel, 2015,

ACB That’s right. As an institution, we also try to have a balance between international female and male experts when it comes to our committees, e.g. regarding our Talents programme. In this context, there’s another aspect that seems interesting to me, which Brett Rogers once mentioned and which we’ve also observed for several years: that in the younger generation, there are even more female than male artists, but when it comes to the mid-career generation, there are fewer women. There’s a Rineke Dijkstra, or a Hellen van Meene, for example, – but they’re exceptions. For their generation, it wasn’t at all usual to become established, and when you did it was over a longer period of time. This I think is a question of generation and is changing nowadays. The conference at Tate Modern shows that we have a stronger awareness of this, and many aspects have changed in society and in the artistic field itself, which makes it easier for women to continue working even if they have children.

DV The question is whether or not the younger photographers are still as active in their late thirties and forties. Many of the issues regarding family and work are still not resolved for women, in most professional fields, not only photography. I’ve just remembered another project – fitting for this conversation – that should be fast-forwarded: Ann Christine Eek’s series from the 1970s titled Working – not slaving to death, about women’s double labour. It’s interesting that this thirty-year old project is very much a contemporary topic.

ACB I think we should see things positively. There are more and more women who are continuing to work even when they have a family. The female artists we’ve presented recently, or are going to present soon, like Niina Vatanen, Viktoria Binchtok or Viviane Sassen, all have children, and they’re still working. I think it’s also, besides social structures, a question of personality.

NS I hope this conference will be an eye-opener that will help us actually reach the desired balance.

DV The conference is highly relevant. It’s important not to relax and think that we’re there already, because we still have a long way to go.

Ann Christine Eek, Annikki, hospital ordely, on her way home with the children. (Nacka, February 1974)