CHARLOTTE COTTON & BJARNE BARE

Dalston Anatomy, 2013, Lorenzo Vitturi. Photo by Petter Berg.

During the last two decades, Charlotte Cotton has been at the forefront of developments in contemporary photography. Artist and gallery owner Bjarne Bare talks to her about institutional challenges and what the future might bring for the medium.

Bjarne Bare Through your various positions, writings and discourse, you’ve been a close witness to the changes in photography over the course of your career, which has taken place over an interesting couple of decades for the medium. Could we start by talking about institutions? You’ve been involved in both institutional spaces as-well-as commercial and independent initiatives, and online projects. I run a non-commercial space myself, and I believe that both commercial and non-commercial spaces have responsibilities in shaping local scenes and thus influencing artists in constructive dialogues. Although larger institutions might be stronger on academic discourse, commercial spaces can bring a visual dialogue by showing refreshing new talent. The role for smaller independent spaces could be to create a closer dialogue with artist and audience. I believe this balance is crucial for the local scene, as well as the international one. How do you see this “dance” working out between various spaces and thus the overall discourse? Does photography differ from contemporary art in general?

Charlotte Cotton I find it really difficult to characterise the changes that have taken place over the twenty years I’ve been working with photographic culture. The subject and the context of the photographic has changed, and I’ve found that about every three years I seem to be working with a new set of militating factors that shape the frame of my thinking. I do feel very lucky that my training was at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where I started working as an intern in 1992. It’s an institution that was founded as, and is still – just about – operating as a place of public service. It was a blessing to be in a position to think about photography as a broad terrain of uses and outcomes and also observe the rapid development of the idea of photography as contemporary art through the 1990s from a vantage point that still had the patina of Victorian ideas about public access to culture. I learnt about photography as a part of material culture and a demonstration of human endeavour, rather than as a subsection of the story of modern and contemporary art with the concomitant concept of art photography as a commodity within a neoliberal marketplace. Because I began my curatorial career in the early 1990s, I developed my relationship with photography partially in a historical mode – it was seen as an underdog section of artistic culture, shaped by its twentieth-century proponents, who formed a separatist history and identity in order to forge the medium’s cultural legitimacy. At the same time, I was learning how to be a curator alongside the first generation of art-school graduates who were confidently creating contemporary art photography, works that were intended to operate within the wider discourses of contemporary art. A general sense of the coexistences that are possible in the photographic realm has been an enduring interest of mine. Bjarne, I’d love to hear from you about your start in photography and how you think it shaped your approach.

BB It’s this rather schizophrenic aspect of photography that’s been keeping me up at night. Your voyage, starting at the V&A, seems ideal for mapping out the various views, uses and opinions regarding a medium that has become accepted to such an extent in society that people rarely seem to question its existence or hidden layers of meanings. My introduction to photography came about as a clichéd image, starting with a trip to Mekhong, where I met a rather flamboyant Russian photojournalist who smoked opium and shot photos with an ancient Nikon F1. I was nineteen at the time, and I began to romanticise the idea of the war photographer: the possible influence one might have within news media, saving the world through important imagery. Photography then brought me to Cairo to meet with professional war photographers, only to hear their stories about the invasion of Iraq and to realise that even the pure war photographers seemed to have become part of a game, where journalism is allowed into certain rooms in the party and the backstage is filled with others who control the guest list. It didn’t suit my romantic vision of the photographic image, and I lost faith in true journalism.

I then looked to art, since it seemed the only place left where a pure dialogue could be had within photography. Here, I also found freedom in terms of storytelling and truth, and a large potential for creation. Tacita Dean has said that ‘in order to deal with fact, it’s best to resort to fiction’. For me, this might be the core of my interest in contemporary art photography, and why I think the medium has evolved in the right direction over the past decade. It seems to have shifted away from the classic narrative of the photography exhibition where every image tells a story, and into a situation where the exhibition space functions more as a total installation and each work contributes to the larger narrative. Here, I believe that photography is finally moving towards contemporary art in its understanding of communication. After all, art boils down to communication. Do you share this idea of the changes within so called art-photography, and do you believe it’s moved further away from other types of photography in recent years?

CC The best photographic practices that I’ve seen haven’t so much moved away from other types of photography, but rather acknowledge the contemporary condition of image-making: namely, that it’s no longer useful to think of photographic practice as pivoting around fixed ideas of types of photographers and better to accept the very unfixed nature of how artistic practice navigates the contemporary media ecology. The photographic practices that resonate for me are clearly embedded within our image-making and disseminating culture. It’s important to acknowledge that embeddedness for what it is: a necessarily close position from which to pinpoint the important things that are happening within our pervasive visual systems. It’s not primarily a strategy for the adoption of the language and behaviour of photographs within mass media and social circulation for its own sake, but the best vantage point from which real and close attention to the incipient nature of image culture can be paid. These artists aren’t venturing out into the broad terrain of image culture to gather up material to take back to a fixed and detached space defined as art – or indeed photojournalism or commercial image-making. If they were, then I think we could call photography the art of the illustrator. The creative processes that I am drawn to rely on finding points of interest and properly reflecting on their meaning and causality. This position enables open-ended practices to unfold. Such practices are at the heart of human creativity and the enduring – pre-photographic – desire to make marks that delineate and are comprehended in our time.

What I also respond to in your previous reply is the sense that it’s important to you that photography is a discursive space – that it’s a discussion between practitioners and viewers, an acceptance that within a ubiquitous image culture, photographic capture is something that’s shared between photographers and their audience.

BB I agree that open-ended practices are the ideal, but they require open-minded practitioners and audiences across disciplines within the medium. I believe this occurs most often in the field of independent publishing, where practitioners have developed a playful approach to the finished work, while it seems to me that the exhibition format still obtains a certain seriousness. This could simply be because the publishing scene is mainly driven by a new generation of practitioners. Within photography, I feel there’s a strong conservative mass, possibly driven by the market, photography fairs or certain medium-specific museums. In photobook-making and self-publishing there’s an open approach to aesthetics, source and output, where sharing is the ideal. Simultaneously, I do have the constant feeling that although photography has evolved technically, as well as becoming increasingly available, the intellectual level hasn’t followed suit. We’re still in a situation where a direct message translates better to the audience than a more complex photograph containing several layers of dialogue. Again, I believe this multi-layered dialogue is found more often within art, and thus is more appealing to me, though I might be the conservative one here. Is this a view you share, and if so, how do you grapple with this when curating a large show for an institution such as The Photographers Gallery, V&A or LACMA, which have such varied audiences?

CC Publishing has been a flourishing area for photographic creativity for a number of reasons. Firstly, the stakes aren’t so high. What I mean by that is that as digital printing has reanimated the small print-run area of photobook publishing, the gap has opened up for photographic projects to embody the book as its primary form, unmodified by the conventions of trade-book publishing. The production costs are potentially less than those of an exhibition and a book is capable of directly reaching an international audience. It’s easy to list the small number of bookstores in cities in Europe and the Americas that will take copies of new books from artists. You can promote and sell directly online and thus reach the niche, and very knowledgeable, audience of fellow practitioners for whom this current creative energy means something. This process doesn’t involve intersecting and negotiating with large and traditional structures like major publishing houses or, indeed, museums and galleries. But I think the book form is also a good ideogram for contemporary photographic practices with their meaning bound up in a dynamic process of production and distribution as inseparable parts of the process of making contemporary art.

When I think about how my own curatorial practices have intersected with this diversification of creativity and the way that we see and talk about it, it’s rarely been in the form of an exhibition in the institutions at which I have worked. Where I have felt this synergy with actual creative practices is when I’ve been curating contemporary fashion photography exhibitions. The nature of fashion photography has pushed me to think about how you narrate the cultural meaning of the collective efforts (rather than single authorship) of image-makers, and how you narrate very temporary stories intended for the lifetime of magazines, not the ‘in perpetuity’ of museums. When I was working at LACMA, I think it was the non-exhibition elements of the programme that carried that discursive spirit, and in particular the website and live discussions that curator and artist Alex Klein, designer David Reinfurt and I created as part of Words Without Pictures. I’m interested in how museums can create iterative frameworks and host the urgent discussions that practitioners want to have. In the past two years, I’ve mainly been teaching in art schools, writing and participating in exhibition projects with other curators. For me, it feels very much like a time to participate in new things and talk out the possibilities rather than try to set things in institutional stone, as it were.

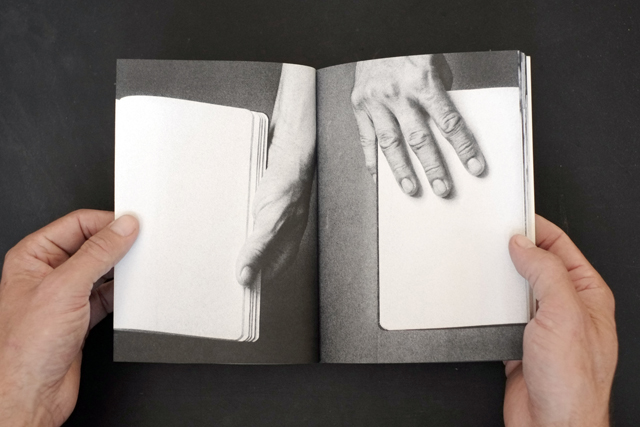

Emil Salto, One hand, and then the other, 2014, Cornerkiosk Press

BB Lowering the stakes and creating effective distribution channels has certainly helped numerous young practitioners to go global while maintaining a relevant local scene. On the other hand, nothing is better than experiencing a large-scale, well-produced exhibition that can ultimately function as a vehicle for inspiration and dreams. Referring back to the open-ended dialogue you mentioned earlier, do you believe it’s possible for larger institutions to achieve more direct dialogue? Since institutions have a responsibility for a broad audience who might be used to the standard formula, I imagine it must be hard to break that core. Do you have any ideas about this, and about the type of practitioners that these institutions should involve to create a more open dialogue? Is it only possible through non-exhibition elements, or have you witnessed successful exhibitions that managed to bridge this gap? Words Without Pictures certainly seemed a step in the right direction, involving the audience directly, as well as the web. Do you feel this happens more easily now that you’re outside the institutional system, and possibly working on shorter-term projects?

CC I agree that what makes this such a game-changing time for photographic ideas is that it’s practitioner-led rather than being defined as a movement within institutions and academia. I imagine it will always be hard for innovative practices to lead the narrative of institutional writing and exhibitions, rather than being subsumed as the ‘illustrations’ for overarching curatorial ideas. Some institutions and some curators find ways to frame their exhibitions that are at least fronted by the idea of ‘practice-led’, with strong intellectual arguments that sensitively survey contemporary artistic practices on their own terms and in rapid, flexible programmes that bring a lot of new ideas into the context of galleries and museums. Some of the more successful institutional and curatorial strategies are ones that consciously attempt to embody the momentum of now – rapidly changing, providing more than one version of the story of contemporary practice, thinking of their desired audiences as going on a journey with the institution and curator. I suppose it’s about creating structures that provide possibilities rather than the definite, concretised idea of contemporary practice. This is one of the reasons why the biennial and triennial format is so successful now – you can make an explicit and definite statement but within a context where there’s another – different but equally strong – statement on the horizon.

Another analogy that you raised earlier is the difference between the rapidity of photobook publishing (and the expanding of the idea of a book into the territory that was traditionally that of the magazine), and the conventional trade book that was the sum total, set-in-stone conveyance of ideas. For me, curating and publishing should mirror contemporary practices in being iterative and inputting into the discourses and dynamics that are at play right now, rather than being about the ring-fencing or historicising of some sections of contemporary artists’ work that can be plausibly made to fit into the linear story of contemporary art as it’s been told so far.

BB Is the practitioner-led aspect part of bringing down traditional hierarchies within the arts? In other non-art aspects of photography, this seems to be the case, but possibly not in favour of photography, since it seems that practitioners are now handling more than one task in the process, often due to budgets. In journalism this seems to be the case, and also in fashion and advertising.

CC I don’t think we’re seeing the dismantling of the traditional hierarchies of arts organisations. That may of course just be a generational consequence: the fact that there simply aren’t enough people at the top of management structures who have a genuine interest in bringing about change that’s responsive to the momentum of creative practices right now or the seismic shift in our collective visual consciousness in the twenty-first century. The business plan of the culture industry places its trust in monographic exhibitions and artists with track records in the market. I don’t think the culture industries are in any way in a different situation at this stage of neoliberalism from their cousins in the creative industries. If you look at feature-filmmaking, the two areas of confidence are the large action-movie blockbusters and the crowd-sourced, ground-swelling independent movies with all their innovation and timeliness. Culture is also polarised in this way, with major museum exhibitions at one end of the scale and artist and independent curator-led initiatives at the other.

BB I think one of the reasons for the popularity of the biennale (and at times the less interesting but equally popular art fair), is that there are fewer set systems. The players change with every edition, always bringing in new hierarchies of curators, artists and thus audiences – keeping the discourse fresh and relevant. This occurs especially in the biennale format, which usually manages to blend all media into a whole. The photography biennales I feel are less relevant, possibly due to a smaller field of players. Although I run a photography space myself, and this conversation is due to be published in a photography journal, I feel we should work towards making these spaces redundant, aiming for a more open dialogue between media. Why do you think there are so many medium-specific galleries, journals, biennales and fairs for photography, while the other arts blend naturally?

CC Photo biennales and festivals have a mixed heritage. They weren’t born out of this era of global contemporary art biennials and art fairs, but had more photographer-led starting points, often in the 1970s, and were forums for practitioners and a small band of supporters to get together to see and talk over what was new. Some, but not all, current photo festivals still carry that heritage, as if photography were a separatist medium. Personally I don’t think that’s true, or at least the narratives and discourses of these festivals aren’t pluralistic or responsive enough to what’s actually happening in photographic practices. Festivals can run the risk of being the meeting point for historical cliques or those who feel disenfranchised from the growth of photography as contemporary art, which is quite ironic given that in the formation of the idea of photography as a cultural subject in the postwar period, its members had to come from somewhere else because the field didn’t exist. If photography festivals continue to be relevant, it will be because they create structures that are actively diverse and make genuine enquiries into the shifting terms of the photographic, both within the context of contemporary art and also within our media ecology at large. I think festivals are better when they align with practitioners and not the market-driven systems of major institutions.

BB I’m interested in how photography has evolved within the exhibition space. The photograph’s ability to show a more complex multilayered message comes forth as photographic exhibitions blend works that don’t seem to fit together at first glance, but create a message as a whole. I see this development more often in galleries and institutions focusing on more than one medium, as if this approach comes from contemporary art rather than the photography world. In addition, I see more and more exhibitions including spatial elements in dialogue with the framed photographic works, thus pointing at the photograph as an object in dialogue with the spatial matter in the room. In this sense, how do you see the future of photography in exhibitions and museum collections? I recall you once stated it was at risk of becoming the watercolour of museum collections.

CC What I meant by the danger of photography becoming a historical form of creativity akin to the watercolour is the risk that photographic practices will stay fixed to their conventions and not re-calibrate so that they still have real relationships with the defaults of today’s image environment. I don’t think that there is this separate intellectual space called art; photographic artists are embedded within the dynamic of the wider visual culture. What you’re alluding to is that often the most timely exhibitions of contemporary practice have made a complete break from the editorial, linear mode of photographic sequencing that morphed from the magazine page to the gallery wall in the late twentieth century. Or indeed, the vogue in the late twentieth century for stand-alone, painting-like tableaux photographs that you were expected to study in isolation. I think you’re talking about installations that may bring photographic qualities into the space of art that come from another area, but done in such a way as to bring each photographic element into a constellation of photographic standpoints whose meaning comes from these contingent relations.

I’m aware that I’m describing the rhizome model of cultural production. The rhizome is a useful model for thinking about the way in which we create dynamic maps of seemingly disparate forms of ideas, their meaning held in the constantly changing connections we make between them. It’s a useful way of thinking about not only the structures of some of the most interesting photographic gallery installations but also the shared way in which we create meaning with the viewer. Just as some of the best artists who work with photographic ideas are constantly questioning and shifting their practices in response to our image world, I’d like to imagine that institutions feel a parallel responsibility not to solidify their working practices. It’s hard to envision such open-ended practices if you view the museum’s responsibilities as exclusively to collect and exhibit objects that are the final resolution of artistic ideas. But if we viewed museums as spaces that also host new ideas that come from outside their collecting purview, sites for open discussion, centres for publishing and disseminating ideas about contemporary human endeavour, and you made this the substantive archive of record, then I think we’d have more belief in what institutions can provide at this mercurial point in photographic culture.

BB If the rhizome model can be used to inform contemporary photographic production, and if I understand the theory right, it does indeed point towards an open-ended dialogue, where several aspects of production inform each other simultaneously, thus creating new perspectives. This is an aspect that I often miss within photographic discourse. Stub by Linn Pedersen (2010) is a good illustration of the rhizome theory. It’s a theory that can point to the core of the ideal practice, not only in terms of exhibitions, but already manifested in book-making and other forms of photography as you mention. You said once that when you started curating, the scene was still dominated by shows focusing on the history of photography, as if the medium were still new to the public. With the young generation growing up with media such as Instagram, making them capable of reading small images swiftly, perhaps we’ll see a strong photographic understanding in the coming generations. As photography spreads so fast, however, the Benjaminian ‘aura’ that photography has struggled to build up over the past century might fade. People are now talking about post-photography; do you feel that the digital photograph distances itself from the genuine analogue photograph by losing its indexicality through the computer process? If so, do you feel that photography is suffering or strengthened in the postinternet/digital generation?

CC Actually, I don’t share that concern that something will be lost, although I do sympathise with such reservations. I don’t think that the actuality of our media environment should stop anyone continuing along the path of a practice that was set in the last century, but what it means to do so has shifted profoundly due to the context of contemporary practice. I definitely share with you a great optimism that artists working with photographic ideas are entirely capable of keeping up with the behaviours and nuanced visual capacities of their viewers. Today’s artists are better considered as shaping their practices as entry points that are legible within the epoch of the maker-consumer, interpreting what’s already the contemporary viewing experience for the dynamic of their work. Contemporary practice doesn’t take specific forms per se – it includes artists working with traditional materials (such as photographic prints, knowingly deployed for their auratic materiality) just as much as artists directly using the vernacular language of online culture, encapsulating the actual and symbolic pervasive impact it has had on the ways we make, consume and read visual culture. We could talk about ‘post-photography’ in the sense of photography as a medium and a discrete discipline of art being a defined entity, but I think the photographic is alive and well; a fitting adjective rather than a solidified noun.

Dalston Anatomy, 2013, Lorenzo Vitturi. Photo by Petter Berg.