TRAVIS DIEHL

David Kennedy Cutler and Sara Greenberger Rafferty, PAPER CUTS 2

Review by Travis Diehl

In the southeast corner of the book fair’s dense acreage—a booth-city large enough to have separate districts for collectables, glossy monthlies, photobooks, zines, porn—was Paper Cuts 2, a display by artists David Kennedy Cutler and Sara Greenberger Rafferty. Hung on the wall above boxes of faux kale and cast iPhones, on peeling wallpaper decorated with blue OS X folders, were six pads of tear-sheets, across which marched columns of PDF icons. Texts by Abate, Michelle; Abing, Hans; Acconci, Vito; and Ackerman, Chantal; preceded dozens by Adorno, Theodor and Benjamin, Walter, in a seamless flight of perfectly laid-out documents—a digital realization, seemingly, of the mechanized library envisioned by Fuller, Buckminster. (Indeed, each text is marked with a green Dropbox icon: successfully shared.) Scanned or otherwise exported from print, each file bore a tiny picture of its first page, top corner folded over as if turning, a strip of black comb binding along the left edge. Amid this proliferation of the art-critical canon, which in six posters barely gets into the Bs, the little texts propose a literally iconic relationship to “real” binders of the sort containing reports, fakebooks, classroom readers—semi-legal compilations for “educational use only.” This detailed PDF icon is Apple’s latest embellishment to the metaphor of the “desktop,” that indispensable surface of human/machine interaction. Even as it evaporates into the cloud, text clings to the suggestion of depth, weight, and substance.

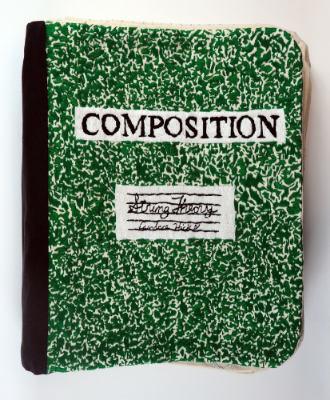

Candace Hicks, Super String Theory, 2014

With Rafferty’s prints as map, one could imagine floating over the fair, above the museum’s many partitions, afforded a perfectly perpendicular view of booths and wares locked to what from this height looks like an orthogonal grid. Yet the “feel” of books is surely one reason for their continued popularity. It’s tempting to see the enthusiastic throngs at the latest LA Art Book Fair, the city’s third, as evidence that print is here to stay. From the ground, the fair spilled over into a dizzying variety of tactile objects—books, posters, zines, stickers, sculptures, drawings, tote bags, even foods—many of which resisted any clean transmutation into binary data. A book of photographs of camouflage screens by Jason Vaughn, for example, came courtesy of TBW Books in a limited-edition wooden box, sealed with a uniquely marred piece of real plywood. Candice Hicks unveiled her Super String Theory, a cloth facsimile of a ruled notebook in which every letter and drawing has been embroidered in thread. A photo by Allen Ruppersberg, however, caddishly propped beside the entrance of the “classroom” (formerly the museum’s reading room, presently cleared of printed matter), perhaps summed up a weary undercurrent: depicting the artist supporting a wavering stack of thick tomes, its title is Too Many Books.

Providing a welcome break from glassy-eyed browsing, the classroom’s discursive program narrowed the fair’s expanded field into a series of presentations, with everyone from artist Lucas Blalock to Bidoun magazine pushing their latest projects. On hand on Saturday afternoon to share their current research with a packed room of sweaty fairgoers were two representatives from the trend-forecasting artist group K-HOLE (whose reports, incidentally, appear on their website as enlarged icons of PDFs fastened by black comb bindings). Best known for spawning the “normcore” meme in the fashion world, they took this unintended proliferation and distortion of their term as the starting point of their talk, which speculated on how their concept of “basic” fashion became, a couple of years later, the misguided “Dress Normal” ads for Gap clothing. One hypothesis was that streamlined, simplified ideas are better primed for transmission than rich ones. Too much context prompts people to parse and parse again, until context falls away. Perhaps, too, there were once fewer “outlets” in the media, restricted to reliable voices and thinkers, while today—witness the sprawl of the LAABF—there are as many pundits as there are people. The group terms the heat death that follows Consensus Collapse. Not that this is a bad thing—or a good one. K-HOLE, like any self-respecting (self-reflexive) think tank, frame their observations with ambivalence. And it does seem true that the current intellectual biome favors those small but sturdy ideas able to survive a harsh separation from context. K-HOLE noted, not without pleasure, that the Gap campaign was a failure—and indeed, how could an idea so hopelessly abstracted from its original complexity hope to register anything more than desperation? Normcore, which became, simply, “New Yorkers dressing like midwesterners,” started as a utopian strategy born of “the belief that we can still control our symbols,” and thus still transmit meaning, even amid the present overload. But how? With artists, maybe, as forecasters and guides.

LAABF teemed with folks who still value a complex context over legibility; the content of a carefully crafted book remains irreducible to viral form. The fair itself, though, as an abstract whole—not so much. Dozens of photos on Instagram tagged with #LAABF show a set of prints dominating another neighborhood of the fair: the letters CRYING AT THE ORGY, superimposed on roses. Ironic it is not—ambivalent, yes. It is an ambivalent age, after all, that joins print products in the Internet of Things.

On the way to the ramp leading up to the mezzanine was The Book Machine, an instant micropublishing effort: visitors could bring and output their very own books—from PDFs, of course. Elsewhere, a psychic laser printer by designer Becca Lofchie answered yes or no questions. How did it work? This digital oracle was powered by a twenty-sided die. Forget sales and attendance numbers: such a glib magic act was as good a predictor as any for the coming state of art books. Meanwhile, one thing is certain: for three and a half days, the LAABF codified with almost meme-like clarity exactly what you, young creative, should be doing with your weekend. K-HOLE darkly hinted as much when they screened parts of lifestyle ads by AT&T and Zara, in which weirdly well-off freelancers drift through bright white live-work spaces, passing over the crisply kerned tools of their trades. As if you required more proof that the products you now “need” in order “not to fail” in your unmoored and artsy profession go not on your bookshelves, but on your desktop.

Still from K-HOLE’s research presentation at the LAABF (image courtesy of K-HOLE)