NICK WAPLINGTON

It’s funny to think back on the photographs that meant a lot to me when I was younger. Not just as a nostalgic reminiscence, but as a way to understand and remember what I saw and liked in them, compared to what I see today. I remember being five years old or so, and loving the photographs by Nick Waplington. Their plush, synthetic surfaces stood out to me. I think of families eating ice cream in rooms with carpeted floors and patent-leather sofas in different shades of pink. The drama and chaos and abundance of people and stuff—which I have now come to see as the images of struggling British working-class homes in the 90s—filled me at the time with an unsettled combination of envy and fascination.

Afterimage by Emma Aars:

Nick Waplington, image from the book Living Room, Aperture, 1991.

It’s funny to think back on the photographs that meant a lot to me when I was younger. Not just as a nostalgic reminiscence, but as a way to understand and remember what I saw and liked in them, compared to what I see today. I remember being five years old or so, and loving the photographs by Nick Waplington. Their plush, synthetic surfaces stood out to me. I think of families eating ice cream in rooms with carpeted floors and patent-leather sofas in different shades of pink. The drama and chaos and abundance of people and stuff—which I have now come to see as the images of struggling British working-class homes in the 90s—filled me at the time with an unsettled combination of envy and fascination. I didn’t notice the cigarette butts on the floor, the stains everywhere, how everything was covered in a shade of dirt, or see the fights as real fights. I saw the girly dresses, soft tracksuits and plastic toys I never got. Waplington’s photos captured everything I felt my own life lacked. I can still recall my obsession with the young girl in a tartan dress trying to cut the lawn with a vacuum cleaner. There was always so much happening, and it always seemed to be so much fun.

A girl in her early teens, leans against the floral wallpaper. An older girl sits on a sofa to her left, along with others who are beyond the frame, while to her right, two younger children attempt to strangle each other. A mother with a pair of infants on her lap and a troubled face speaks to someone in the room from deep down in her red velvet armchair. Our girl has red-brown hair and a sharp face, and her hands are in the pockets of her way too big pink sweatpants, pulled up at the ankles, showing her dirty white sneakers on the wine red carpeted floor. She watches her family from a distance, as if she were the photographer—not indifferent, but reclusive in a sense. She acknowledges, but she does not participate. She is a grounding element amongst the chaos in the image. There is a self-consciousness underneath it all. Some are looking at themselves being looked at.

This text is taken from the essay Eye as a Camera, Objektiv #28. Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

RAGNHILD AAMÅS

You send me an old image of yourself somewhere in the West, near where I grew up. A squinting, grinning child, facing the sun, feeding a lamb, one hand holding on to a metal string fence. There is text written over the image. An invitation. But my mind is distracted by another image, and we text about it. I'm leaning on the hope that in our knowledge of the fickle status of images, of their bending, we still have a capacity that can help us think, even when we're distracted.

Afterimage by Ragnhild Aamås:

You send me an old image of yourself somewhere in the West, near where I grew up. A squinting, grinning child, facing the sun, feeding a lamb, one hand holding on to a metal string fence. There is text written over the image. An invitation. But my mind is distracted by another image, and we text about it. I'm leaning on the hope that in our knowledge of the fickle status of images, of their bending, we still have a capacity that can help us think, even when we're distracted.

I thought I was beyond the effects of them, the images. We live in far too interesting times. But this one hits my inbox, in a newsletter from a newspaper I follow. I register it in my side-view while I'm working on a wooden figure.

It is not, I think, the aesthetics of the image, its sensuous reach, that strikes me, nor the indignation of the suffering, but rather a mimetic response that lands like a fist. A child sitting on her mother's lap, with a calm, almost angelic face. She looks the same age as my daughter EY. Like any other child, she is quite content to be on a parent's lap, regardless. The mother is hunched over, her face distorted by muscle and emotion, far from calm. Around her, women and children sit on the dusty floor, their wounds treated in various ways. In the background: a rubbish bin with a black bag, a plastic tube sticking out, empty packaging for bottled water, a five-litre container of some liquid in front of it, protected by cardboard. There is familiar street wear, dust-covered black backpacks on the floor, several darkened reflective surfaces of depowered screens. A bald man, propped up halfway between wall and floor, with bloody cotton swabs on his head, clutches a mobile phone, his face an empty field. As a group in a setting, they conform to what Susan Sontag quotes as Leonardo Da Vinci's instructions for showing the horror in a battle painting:

Make the defeated pale, with their eyebrows raised and knit, and the skin over their eyebrows furrowed with pain ... and the teeth apart as if crying out in lamentation ... Let the dead be partly or wholly covered with dust ... and let the blood be seen by its colour, flowing in a sinuous stream from the body to the dust (Regarding the Pain of Others, 2003).

I wonder if they have consented to have their pictures taken. I wonder in whose feeds the picture will appear, and with what caption.

Wait, there is something nestling in the stillness of the child's face: a quiet place, a silence, a projection beyond

Has motherhood, parenthood, the carrying of responsibility, rekindled in me a certain need to no longer ignore politics? Or let's put it this way: it seems to have attuned me to the fragility of things, to the integrity of the body, and to a certain stickiness of time (EY, who I'm calling as I type, has been intruding on me since she came home from kindergarten on the third day with an eye infection – and we have sterile saline water). There is a feeling of being turned upside down, but this is balanced by obligations of care, in the sense of Juliana Spahr, a micro-dose of contempt for the ethnostates and the ongoing governance of death.

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag points out that suffering is always at a distance; in a sense, we can never be close enough. In the confrontation with images, there remains a central potential for empathy. But it is not independent of narrative and the ability to place oneself in the privileged position of having distance from immediate suffering, from the unfolding hierarchy in which the damage is received and captured.

Who is not in the picture? What is not depicted? What subject is not as easily captured as suffering? Could I imagine that the eyes of the child, who is certainly not looking at the lens, are staring at something beyond, at something responsible, at the ideology of nation states? Not somewhere else, but here.

Image: Aamås’ screenshot from inbox of newsletter showing photo by Mohammad Abu Elsebah / DPA / NTB). Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series explores which visuals linger and take root in today's endless stream - much like a song that plays on repeat in your head. Whether it's an image glimpsed on a billboard, a portrait in a newspaper, a family photo from an album or an Instagram reel, we're interested in those fleeting moments that stay with you and refuse to let go.

SPARE RIB

The image that occupies my mind these days is a photograph of the editorial team behind the feminist magazine Spare Rib. We see them posing on the windowsill of their office in Soho, London. The photograph was taken in 1973 by a photographer whose name we no longer know. Like many other self-published and independent publications, Spare Rib was built on friendship, collaboration, and countless hours of unpaid labor.

Afterimage by Nina Mauno Schjønsby:

Certain Shadowy Parts

The image that occupies my mind these days is a photograph of the editorial team behind the feminist magazine Spare Rib. We see them posing on the windowsill of their office in Soho, London. The photograph was taken in 1973 by a photographer whose name we no longer know.

Like many other self-published and independent publications, Spare Rib was built on friendship, collaboration, and countless hours of unpaid labor. Written by women and focused on women's issues, the magazine addressed topics such as domestic violence, women’s mental and physical health, and the lack of equality in education and work. It was founded by two English women, Marsha Rowe and Rosie Boycott, in 1972. They were soon joined by others, among them Irish Roisin Boyd and Nigerian Linda Bellos.

One of the reasons why this image resonates with me, may be that it stands in for countless others that were never taken or published, images of other independent editorial teams emerging from marginalized or suppressed positions. Spare Rib, along with many feminist magazines both before and after, shows how people can create a space together – a micro-public – where they define what should be said and how. For me, this photograph represents the feminist community necessary to produce such a magazine. It also illustrates the solidarity, even in the midst of the disagreements that I know existed among them.

Today, Spare Rib has successors such as the London-based zine OOMK, which focuses on Muslim women, Belgium's Girls Like Us and Norway's Fett.

Editorial processes and the various stages of creative work are often invisible. Once a magazine has gone to press, its history closes in on itself. Perhaps this has always been the case. In my book Gi meg alt hva du kan (2024), I write about how, in the 1830s, Camilla Collett and her friend Emilie Diriks taught each other to write and explored the conditions of their lives through an intense correspondence. Their collaboration culminated in the handwritten magazine, which they called Forloren Skildpadde. In this way, two young women created their own intellectual space. This is Norway's first feminist magazine and an early forerunner of feminist publications such as Spare Rib.

I am fascinated by how, through intimate conversation and close collaboration, something bigger than oneself can emerge. Zines, magazines and small press publications still give a voice to marginalized perspectives and shed light on issues that might otherwise remain in the shadows – what Camilla Collett once called "certain shadowy parts.”

And there they sit, the editorial team of Spare Rib, the magazine that would survive until 1993, despite editorial disagreements and financial constraints. They occupy a place between a private sphere – their editorial office – and a public sphere – the street outside. For me, this image symbolizes how an intimate dialogue between friends or colleagues can be the beginning of something much larger: a multifaceted conversation that eventually turns outwards into the public sphere, branching out and reaching us even now.

TUNGA

‘How's your hair?’ my friend and I text each other during hectic times when we haven’t been in touch for a while. We exchange messages about different styles—flat or high—without needing further explanation. We both know what frizzy means. My last reply to her included a picture of a king at Versailles, his hair big and fluffy. I hope we keep asking each other this question until our hair is white and beyond. I think of my friend when I see a picture of the Tunga twins tangled in each other's hair. The image is inspired by a supposed Nordic myth about conjoined sisters who caused trouble in their village.

Performance of Xifópagas Capilares entre Nós at Fundição Progresso, Rio de Janeiro 1987. Courtesy Wilton Montenegro and Instituto Tunga

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

‘How's your hair?’ my friend and I text each other during hectic times when we haven’t been in touch for a while. We exchange messages about different styles—flat or high—without needing further explanation. We both know what frizzy means. My last reply to her included a picture of a king at Versailles, his hair big and fluffy. I hope we keep asking each other this question until our hair is white and beyond.

I think of my friend when I see a picture of the Tunga twins tangled in each other's hair. The image is inspired by a supposed Nordic myth about conjoined sisters who caused trouble in their village. The image is striking, impossible to miss - two young girls, in their teens, looking at each other, holding their long, shared hair in their hands. I can see their profiles, their noses. Why are they still together? They could let go.

I walk past a poster with a quote from Coco Chanel: ‘A woman who cuts her hair is about to change her life.’ I think of another friend who bleached his hair and claimed it would change everything. I wonder if it did.

Later, in a café, I search for more information about the twins and come across a description where the artist references a mythical text attributed to a Danish naturalist. As I scroll further, I learn that the conjoined twins were sacrificed upon reaching puberty, and that when a woman began to embroider with hair taken from them, it turned to metal and became gold.

On view in GROW IT, SHOW IT! A Look at Hair from Diane Arbus to TikTok at Museum Folkwang, Germany.

ELSE MARIE HAGEN

There are lots of images and impressions from this year's annual exhibition, but Else Marie Hagen's puppy is the one that stays with me after the visit. All the way up the stairs to the sky-lit halls of Kunstnernes Hus we are guided by Asmaa Barakat's work. With golden letters she asks: please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind...

Else Marie Hagen, Stilleben, 2023.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There are lots of images and impressions from this year's Autumn Exhibition, but Else Marie Hagen's puppy is the one that stays with me after the visit. All the way up the stairs to the sky-lit halls of Kunstnernes Hus we are guided by Asmaa Barakat's work. With golden letters she asks: please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind... لطيفا كن... please be kind... The work was made after the artist repeatedly met a woman on a bus who 'looked deep into my eyes for a few seconds and down into my shoes.’

There is also Serina Erfjord's embroidered work from Dr Mahmoud Abu Nujaila's photograph of the last message on the notice board at Al Awda Hospital in Gaza: 'Whoever stays until the end will tell the story. We did what we could. Remember us.’ Or the phone call between Israa Mahameed and her mother, between Norway and Palestine, in A Random 13 Minutes, both keeping the conversation going amidst the terrible sounds from outside the mother's house.

These three works leave this writer in a certain state in the encounter with Hagen's still life. A photograph of the currently deaf and blind puppy trying to orient itself on the desk by the window where someone left it. Around it, a random clutter, which Hagen writes: ‘can be associated with a young person who might have something in common with the puppy.’

For what do we do, what can we do, the people inside in Gaza could see us as blind and deaf as this animal. They have every right to feel abandoned, nothing has changed in these past eleven months. The annual autumn exhibition aims to be a challenge by showing contemporary art, writing that: ‘Anything that shakes our sense of security seems provocative. Contemporary art is often such an unexpected encounter.’

When I look at this work, I'm reminded of a colleague's answer to his daughter's question about what he did in his studio all day. He said that sometimes he looked at a photograph he'd been making for a long time. When she asked him why, he said that for him the picture could work as a question mark, something for others to figure out, like this animal trying to understand the world. And then, if it really works in a provocative way, it can become something more, something bigger, something that can help change things. Like Hagen's. Possibly.

ROMANE BLADOU

I've been thinking about which picture to choose this weekend and it's hard. There are so many, some that are actual images that you've seen, and then some that you wonder if they're just a memory or something that someone told you about. I've narrowed it down to one that's really stuck in my head over the last few years. It's a photograph I saw in a book when I was in Newfoundland, it was a book about the history of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, a black and white photograph of a house floating in the bay.

Moving a house in Trinity Bay. Ca 1968. From the Collection: Resettlement Photographs, Maritime History Archive.

Afterimage by Romane Bladou:

I've been thinking about which picture to choose this weekend and it's hard. There are so many, some that are actual images that you've seen, and then some that you wonder if they're just a memory or something that someone told you about.

I've narrowed it down to one that's really stuck in my head over the last few years. It's a photograph I saw in a book when I was in Newfoundland, it was a book about the history of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, a black and white photograph of a house floating in the bay. It's being pulled by some small boats towards the hills in the background. And it was taken at a time when there was a policy of relocation, of resettlement within the province. People who lived in very remote places, in isolated parts of the Canadian coast, were asked, forced in a way, to leave their homes and peninsulas in order to move to places where there were jobs, hospitals and services. And they did this by floating their houses across the bay. The image stuck in my head. I had no idea you could do that. And it also felt so poetic. It was just this house floating to somewhere else. And I kept thinking that they would be living in the same home they had lived in all their lives, walking on the same floors, but with a completely different view outside the window every day. Even the light in the house would be different. Maybe they could see from the window where they used to live. I don't know.

In a way, I think what resonated with me is also this relationship to home, especially as an artist, we're always travelling. Maybe this image acts as a metaphor – it is about this desire to be anchored and grounded somewhere, but at the same time this constant pull to go to other places. So it's always in my head, I guess. In a different context, I wish I had a floating house.

ADAM BROOMBERG & RAFAEL GONZALEZ

What do we do with the silent ones? The ones who still say ‘It's complicated.’ What do they think when they're on social media? Have they muted the reels? Can't they see what's happening?

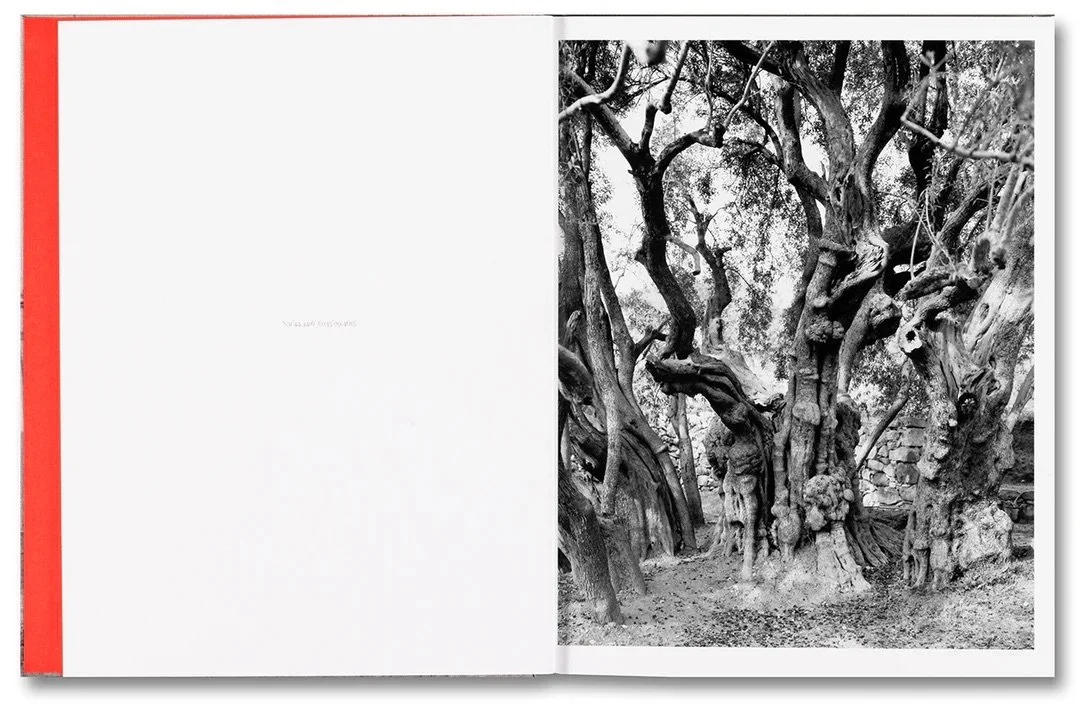

They could get this book. Maybe these colourless, seemingly neutral images of trees would help them to see the true horror. It would be hard to find more violent and beautiful images. From Irus Braverman's text I learn that: ‘Of the 211 reported incidents of trees being cut down, set ablaze, stolen or otherwise vandalised in the West Bank between 2005 and 2013, only four resulted in police indictments.’ This has been allowed to happen. Just like the daily bombings.

Afterimage(book) by Nina Strand:

We share posts in solidarity. We sign campaigns. We go to marches because doing nothing is not an option while this goes on. Today, I see a young couple who look as if they’ve just stepped out of a Woodstock film: long hair, loose clothes, seemingly free spirits. They stand close together. While a politician speaks into the makeshift microphone—no one can hear her—I continue to watch them. His moustache is like Salvador Dalí’s, his shirt is tie-dyed, he’s one hundred percent in character. I've seen him before, at another demonstration, but with a different girl. Is this how he dates, by proposing to meet at a demonstration? In any case, it’s for a good cause. I'm so fascinated that when the rally is over, I follow them into a café and find a table nearby.

In my bag I have the book Anchor in the Landscape by Adam Broomberg and Rafael Gonzalez: black and white photographs of trees in the Occupied Territories of Palestine. Each page has a photograph on the right and the geographical location on the left. A sentence about the book haunts me. Since 1967, 800,000 Palestinian olive trees have been destroyed by Israeli authorities and settlers. Eight hundred thousand trees... I read about olive trees. They grow slowly.

I overhear the moustache say that he used to cry when everyone shouted 'Let the children live' at the demonstrations for Palestine. Now he's worried about not shedding a tear. Has he become numb? The number of dead and missing Palestinians is unimaginable. I hear them talking about a friend who does nothing, no posts shared, no signatures. What do we do with the silent ones? The ones who still say ‘It's complicated.’ What do they think when they're on social media? Have they muted the reels? Can't they see what's happening?

They could get this book. Maybe these colourless, seemingly neutral images of trees would help them to see the true horror. It would be hard to find more violent and beautiful images. From Irus Braverman's text I learn that: ‘Of the 211 reported incidents of trees being cut down, set ablaze, stolen or otherwise vandalised in the West Bank between 2005 and 2013, only four resulted in police indictments.’ This has been allowed to happen. Just like the daily bombings.

When the woman tells her date that she struggles with sharing images of dead people, I almost join them at the table in agreement. I still worry about what it does to us to see them. I understand what a colleague said to me, that the Palestinian people want us to share, want us to see and understand. I share everything except pictures of lifeless bodies. When I wrote a post asking those with children to think about what they post, she told me off: ‘Who am I to decide?’, she wrote. I’m still not sure if she’s right. But I wonder more about those who do not share. I believe in doing something.

I actually got the date for today's demonstration wrong. I went to the square yesterday. It was just me and a Palestinian flag that someone had left behind. I spent some time there. Alone. Saying ‘Free, free Palestine’ several times. When I pass it on my way home, the flag is still there.

YOKO ONO

There is a guy trying on the piece, his girlfriend is filming it. He laughs a lot, a little too loudly, as he tries to work out how best to wear it. It's just a bag, my friend whispers. I look over at a film at the other wall just as a small piece of the artist's black clothing is cut off at the breast, revealing a white silk slip. Why cut there and not more politely where the others have cut small pieces?

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

Yoko Ono, installation view of Bag Piece, 1964, in “YOKO ONO: MUSIC OF THE MIND” at Tate Modern, London, 2024. Photo © Tate (Reece Straw). Courtesy of Tate Modern.

There is a guy trying on the piece, his girlfriend is filming it. He laughs a lot, a little too loudly, as he tries to work out how best to wear it. It's just a bag, my friend whispers. I look over at a film at the other wall just as a small piece of the artist's black clothing is cut off at the breast, revealing a white silk slip. Why cut there and not more politely where the others have cut small pieces?

There is a small statement next to the bag piece where the artist explains that you can see the world from it and talks about how when you are in a bag you become just a spirit or a soul, everything about race, age and gender falls away. The man in the bag sits very still, he might wonder where his girlfriend went, I see her looking more closely at the instructions on how to make a painting for the wind at the wall opposite.

After a while, the man emerges from the bag and shakes it a little before folding it neatly and handing it back to the museum assistant. That last gesture was like a more genuine performance my friend says.

We discuss trying it on, and I look back at the film, just as the same person cutting a hole in the bust is busy cutting off the bra. The film ends where the artist covering her breasts with her hands. It is shot in black and white, I wonder if she is blushing. It will still be me in the bag. There is no possibility of an escape. I suggest we move on.

JOAN JONAS

She has been called the Pippi Longstocking of the art world, my colleague informs me as we enter Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning at MoMA. In the first room there is an image from Jones Beach Piece (1970), a person standing on a ladder going up to nowhere, wearing a white hockey mask and holding a large mirror to reflect the sun back to the spectators. I thought about this gesture, involving the audience, throughout the show. In many of the rooms, Jonas’ playfulness shines through and the performances evoke a sense of community. Several of the videos involve students with whom Jonas has worked, and I wish that I could have been one of them.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

JOAN JONAS. Jones Beach Piece mirror on ladder, 1970, printed 2019. Photographed by Richard Landry. (The image found at Gladstone Gallery.)

She has been called the Pippi Longstocking of the art world, my colleague informs me as we enter Joan Jonas: Good Night Good Morning at MoMA. In the first room there is an image from Jones Beach Piece (1970), a person standing on a ladder going up to nowhere, wearing a white hockey mask and holding a large mirror to reflect the sun back to the spectators. I thought about this gesture, involving the audience, throughout the show. In many of the rooms, Jonas’ playfulness shines through and the performances evoke a sense of community. Several of the videos involve students with whom Jonas has worked, and I wish that I could have been one of them.

Being like Pippi Longstocking is no bad thing: her motto was, 'I've never tried this before, so I think I should be able to do it,' and this applies to so much of Jonas's pioneering work in video and performance. Later, in the museum shop, we see Jonas with her cane and dog in tow, here to give a talk. ‘What a fantastic show!’ I say to her in passing; she thanks me and moves on quickly, but that’s enough for me: just to see the woman who, according to the text on the museum's website, ‘began her career in New York's vibrant downtown art scene of the 1960s and 70s.’

I thought a lot about solidarity, generosity and a sense of community after seeing the show, and wonder where to find this today. Another colleague told me that he had visited Louise Bourgeois in New York, in her home, for one of her Sunday salons where she invited young artists. I thought of this, and of Jonas, when I later visited the exhibition Forks and Spoons at Galerie Buchholz, curated by Moyra Davey, where she weaves her stories and thoughts about each artist into the film that opens the show before we see the photographs. I wondered if I could find some of the old art scene spirit by visiting Francesca Woodman’s apartment in Tribeca. I learned from the film that Betsy, her old flatmate, still lives there, now with her 21-year-old daughter, in what she has jokingly called Grey Gardens. And another photograph, New York, New York, from 1977, by Alix Cléo Roubaud has some of Jonas’ playfulness: a big white canvas with a picture at the top of a small group of people in the park.

I'm thinking about what the strict customs officer asked me when I landed: ‘Are you here on business?’ and I said ‘Yes,’ but then his forehead wrinkled and I was worried mentioning anything about work might lead to not being accepted, so I blurted out: ‘Well, I'm an artist, here for the Art Book Fair. I'm not sure if a visit made by an artist with no money would qualify as a business trip?’ He didn’t find it funny and I should know better than to make a joke. But I could tell him now that this trip has made me very rich indeed.

LUCAS BLALOCK

2. I am ‘here’ because I read Moby-Dick in 2007 and then—as a middling young, near 30, white North Carolinian, at odds with my body, psychically askew, still working in a restaurant, and trying to get out of a situation I felt I was never really meant to be in—I almost immediately moved back to New York from the US South.

I am ‘here’ because I loved that book, which surprised me. And I warmed up to the coincidence that photography had been invented not long before Moby-Dick was written.

2. I am ‘here’ because I read Moby-Dick in 2007 and then—as a middling young, near 30, white North Carolinian, at odds with my body, psychically askew, still working in a restaurant, and trying to get out of a situation I felt I was never really meant to be in—I almost immediately moved back to New York from the US South.

I am ‘here’ because I loved that book, which surprised me. And I warmed up to the coincidence that photography had been invented not long before Moby-Dick was written. It kind of stopped me flat, and made me think about this time of immense shift and how the ascendency of photography had changed the world. It recontextualized what I was doing with a camera and tied it more deeply in to other structures—my experience as an American, and as my parents’ kid—and I thought maybe I’d been thinking about this photography thing all wrong, giving it short shrift, not taking as seriously as I might its contribution to our fundamental condition.

I am ‘here’ because it became undeniably evident to me that photography has been a central player in the world since then. Vilhelm Flusser writes in Towards a Philosophy of Photography that there are only two real turning points in human history— the invention of linear language, the basic building block of historical understanding, in the second century and the invention of the technical image, which mystifies historical thinking, in 1839. Photography has become a, if not the, lingua franca of the world I live in. The invention of photography and The Whale marked similar transitions into the modern. Ishmael’s world and ours became very different by the time they were done.

From Why must the mounted messenger be mounted? by Lucas Blalock. Order it here.

CLIFFORD PRINCE KING

This. Lying on a mattress, kissing. The poster on the wall trying to hold on. The uncertain installation, the importance of inclusion. There is so much in it. The statement of having the person portrayed on the wall. How this couple may or may not have discussed politics before they just had to lie down to get closer. At the top of the poster, a drawing. The face of a person looking down on them. The grapes in the corner, envious like me.

Clifford Prince King, Poster Boys, 2000.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

This. Lying on a mattress, kissing. The poster on the wall trying to hold on. The uncertain installation, the importance of inclusion. There is so much in it. The statement of having the person portrayed on the wall. How this couple may or may not have discussed politics before they just had to lie down to get closer. At the top of the poster, a drawing. The face of a person looking down on them. The grapes in the corner, envious like me.

My friend sent it. It's from a show she's working on with another curator. They use the line: ‘Don't we touch each other just to prove we are still here?’ in the title. It is from a poem by Ocean Vuong.

The photographer has said in an interview that he gets inspiration from people-watching, stating: ‘It’s almost like seeing something precious happening, and as a photographer, you want to capture it, but usually, it passes by too quickly, so I try to recreate those kinds of moments but make them Black and queer.’

I remember a student I did a portfolio review with, she'd made a book on what love was and said it was because she didn't know. She was 23 and had never been in love. The book was full of pictures of couples cut out of advertisements. She couldn't find any real people in love. I know this by King is staged, but it is still truer than an ad. She should see this image.

From the upcoming exhibition at Princeton University Art Museum: ‘Don’t we touch each other just to prove we are still here?’ Photography and Touch.’ Curated by Susannah Baker-Smith and Susan Bright.

WALKER EVANS

While the documentary image is haunted by the decisive moment, the studium calls for a more refined and contemplating dialogue. An unfinished message that seeks context in order to be read. Walker Evans seems to hold a special photographic gaze. Jean-Paul Sartre describes a person entering a bar and gazing through the locale, but as soon as the eye catches another eye, the gaze disappears, the magic is broken.

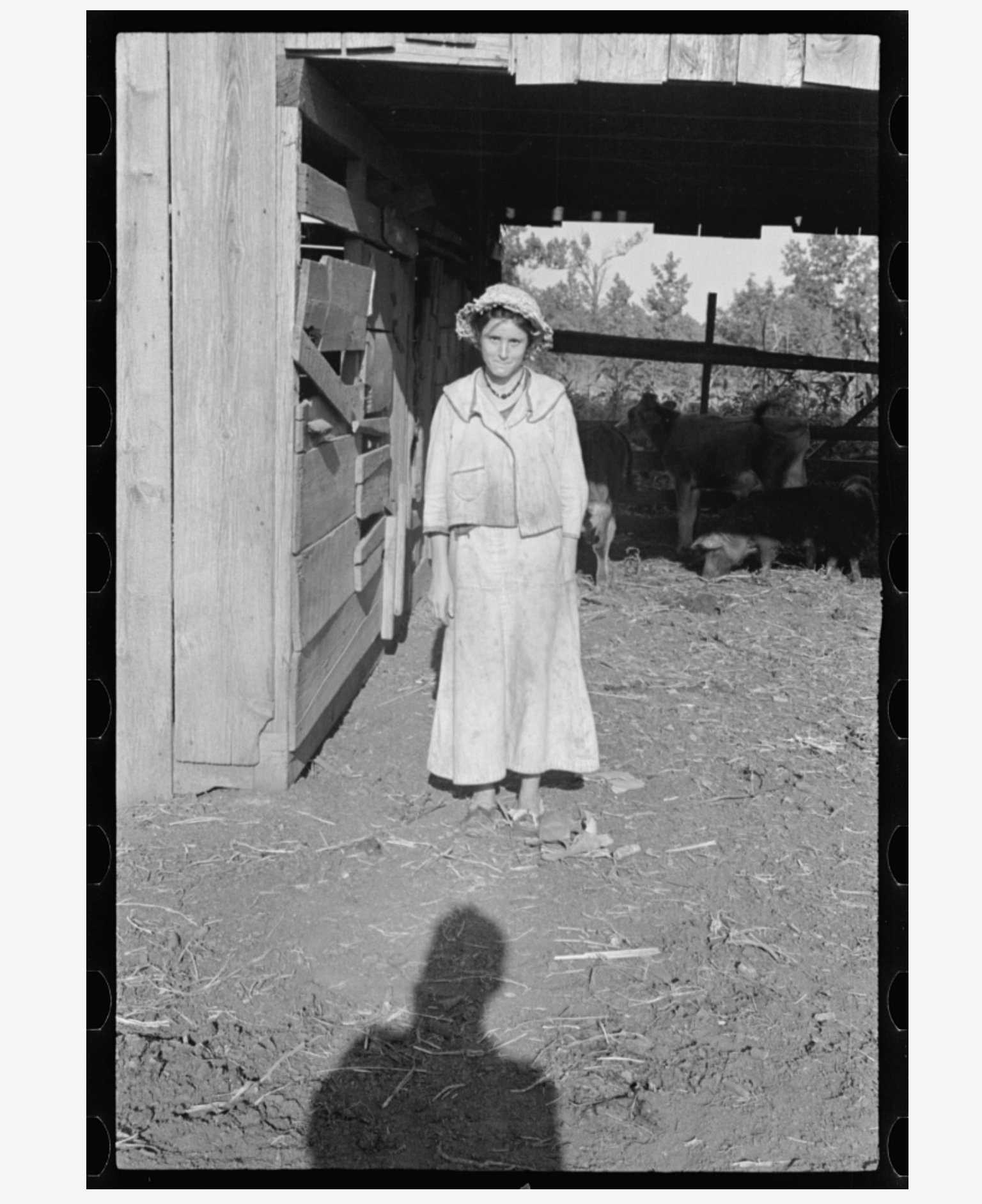

Afterimage by Bjarne Bare:

While the documentary image is haunted by the decisive moment, the studium calls for a more refined and contemplating dialogue. An unfinished message that seeks context in order to be read. Walker Evans seems to hold a special photographic gaze. Jean-Paul Sartre describes a person entering a bar and gazing through the locale, but as soon as the eye catches another eye, the gaze disappears, the magic is broken. ‘I no longer see the eye that looks at me and, if I see the eye, the gaze disappears.’ In such, I find Evans photographic work function as a pensive gaze more than a straight photographic document. Or as Lacan puts it: ‘In our relation to things, in so far as this relation is constituted by the way of vision, and ordered in the figures of representation, something slips, passes, is transmitted, from stage to stage, and is always to some degree eluded in it — that is what we call the gaze.’

When documenting Floyd Burroughs’ family and home for Let us Now Praise Famous Men in 1936, Evans’ isolated focus on the objects caught my eye. A chair flanked by a white sheet and a broom. An empty bed. A pair of workers shoes. Utensils. Along with the portraits he made, the closeups of details describe the life and situation more than the actual faces. As if, in the portraits, the gaze is broken. Along with the use of his gaze, Evans also distances himself from the traditional mode of documentary practice. There is little or no action in his photographs, yet we do experience the situation, through the focus on details. The images are silent, and their immanent communication is key. They are studies. In this, a photographic language develops, one which is more formal, perhaps, but also stays away from the usual photographic realism, where motion, portraiture and action is the modus operandi. When focusing on objects, such as the boots in the negative space, the empty bed, or the chair flanked by the broom and sheet, Evans lets the image breathe, look at you, rather than having the person in the image speaking. It is as if Evans trusts the image, the photography and its silence.

Walker Evans, Dora Mae Tengle, sharecropper's daughter, Hale County, Alabama, 1936.

While writing this, I remembered seeing an image of Evans included in an exhibition at Standard (Oslo) in 2013. The exhibition included mainly contemporary work, and I was puzzled by the inclusion of the Evans piece. I am now, perhaps, understanding this better, as if it was an ode to Evans’ mind and eye. It is hard for me to define the postmodern project in photography, although it carries importance. I find the time we are in, photographically, somewhere in between modernity and postmodernity – and thus work created today should be informed by both. If a documentary approach still can be relevant, or at least exist, the straight photographic document is no longer enough – as if its naiveté is broken. Narration is no longer key. The images look back at us, and we are better informed in reading them now than ever before. In looking at Evans’ work dating nearly 80 years back, I have found relevant use and understanding of the photographic image. In Dora Mae Tengle, sharecropper's daughter, Evans’ Friedlander-esque approach reveals something to me. Not only does he include himself in the image (there is a similar approach among his images of flood victims), but he also destructs the gaze, creating a similar effect as to the more recent Gazing Balls by Jeff Koons. The neutrality of the image is broken, the image looks back, and the photographer is present. This – what seems to be a simple snapshot – holds so many layers of photographic understanding. Along the other work by Evans’ it makes him a highly relevant photographer in the quest of understanding the potential for the straight image in a contemporary discourse.

TONY HANCOCK

This is a film still from the Tony Hancock movie The Rebel. A film about the accidents that lead to success in an art career and of ambition winning out to talent before once again giving way. It is a film about the ‘value’ of art, about patronage, about marketing art and about art’s frustrations as a vocation and career.

Afterimage by Clare Strand & Gordon McDonald:

This is a film still from the Tony Hancock movie The Rebel. A film about the accidents that lead to success in an art career and of ambition winning out to talent before once again giving way. It is a film about the ‘value’ of art, about patronage, about marketing art and about art’s frustrations as a vocation and career.

This comedy, for those who are not familiar with it, charts the journey of a bored junior businessman from London who daydreams of the bohemian lifestyle of the Parisian art scene of the late 1950s and early 60s. He chisels at concrete blocks in his small boarding house room to create his giant vision of Aphrodite at the Waterhole, and paints naïve canvases of birds in flight or a disembodied foot – all whilst wearing his artist’s uniform of a smock and beret. Eventually, he loses patience with the life he is born to and flees to Paris, where he accidentally gains success with his flatmate’s paintings and becomes the toast of the city. His ego becomes bloated and enjoys everything that this fame brings – including the credibility he craves, money and the adorations of the rich and influential. He is, despite this, a man in an alien world and ill-prepared for the part he must play. He is eventually found out as a sham – not one of the people who is born to this world of privilege and culture, but an intruder.

It was in 1992 on our first day at art school, in a college-wide screening of this film that we first met and talked. Strand handed a Softmint sweet to MacDonald and MacDonald broke a tooth on it. The message of the film and the trauma of Strand’s kind gesture left a big mark on us, and the discussion about what is art and what is not has been our constant preoccupation as MacDonaldStrand ever since. Our understanding of our position as intruders in a world we were neither born in to has also been constantly informed by this film.

TAYSIR BATNIJI

There is a face, I can see the eyes. The green and fragmented screenshot is divided into five. At the top I see a light switch. Then there is a green stripe covering the top of the face. Then I see the eyes looking back at me, before another green stripe. The bottom of the photograph shows the shoulders of the person the photographer is talking to. It looks like a woman in a halter top; it could be summer. Taysir Batniji’s book Disruptions shows screenshots of video calls with his loved ones in Gaza, taken between 2015 and 2017.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There is a face, I can see the eyes. The green and fragmented screenshot is divided into five. At the top I see a light switch. Then there is a green stripe covering the top of the face. Then I see the eyes looking back at me, before another green stripe. The bottom of the photograph shows the shoulders of the person the photographer is talking to. It looks like a woman in a halter top; it could be summer. Taysir Batniji’s book Disruptions shows screenshots of video calls with his loved ones in Gaza, taken between 2015 and 2017.

The light switch has such a prominent role in this picture. We never really see or notice it in real life. We just touch it, absentmindedly. I wonder if it is still there, if the house where this person lived is still there. In other pictures in the book there are streets, houses, more people, more life. There is probably nothing left. The word 'noise' is used in the press release about the images. It is true: they are noisy. Even more so – in some ways – than the images of Gaza shared daily on social media. We do what we can. We share. We watch it live. We cry with the parents holding the impossibly small white body bags.

At dinner last night a friend said that nothing can be saved at this point. We watched the reel of the doctor risking her life, running across a road to help a man who's been hit by a car. Another of a mother and child in the street. The mother is still. Hit by a sniper. The child is alive, and so there is a rescue. The child is carried to a doctor who runs with him to a hospital. We all know that the child isn’t safe, not even there, since the hospital might be hit next. There are no rules anymore. The Israeli politicians just carry on. I think of my friend from Tel Aviv who posts about the Israeli hostages. I think about them too, but this was never about what happened that October day.

The blurriness of Batniji’s images from Gaza came to mind when I saw the work of Mame-Diarra Niang at the Cape Town Art Fair this weekend. A work from the series Morphologie du songe (Morphology of Dreams) was on display at the Stevenson’s stand. Something Niang said in an interview about the series echoes the distorted screenshots: ‘This series feels like the abstract idea I have of myself, the acceptance that forgetting is also a starting point and a fleeting, necessary memory.’ I struggle with the idea of how to go on after seeing what is happening in Palestine, but I find comfort in reading these words in a country once torn by violence that now seems to be on the right side of history.

From the dedication on the first page of Batniji's book, we learn that he lost his mother in 2017. Since the beginning of the Israeli bombardment in 2023, he has lost 52 further members of his family. Tell me, what do we do now? We continue protesting, watching, sharing these disrupted images that haunt us. As Taous R. Dahmani writes in her essay at the end of the book: ‘Photography’s (absurd) quest to “tell the truth” might actually lie in fables, not realism. The abstract value of the glitch establishes a new type of document: evidence of the instability that rules over the Palestinian people, and of the survival of images, despite it all.’

Taysir Batniji, Disruptions, 2024. With the essay On What Subsists and What Persists, in French, Arabic and English, by Taous R. Dahmani. Designed & Published by Loose Joints. All profits go to NGO Medical Aid Palestine.

BERENICE ABBOT

This photograph by Berenice Abbott from her astonishing project Changing New York (1935–39) has been my desktop background for the past five years, as it reflects my interests in the urban landscape, biography, affect, paratexts, composition, and technique. As with other photographs I love, I secretly wish I’d made it, despite the temporal impossibility.

Berenice Abbott, Fifth Avenue, nos. 4,6,8, New York, 1936, printed 1982, Gelatin silver print. Gift of A&M Penn Photography Foundation by Arthur Stephen Penn and Paul Katz, 2007. The Clark Art Institute, 2007.

Afterimage by Arturo Soto:

This photograph by Berenice Abbott from her astonishing project Changing New York (1935–39) has been my desktop background for the past five years, as it reflects my interests in the urban landscape, biography, affect, paratexts, composition, and technique. As with other photographs I love, I secretly wish I’d made it, despite the temporal impossibility. I admire the picture’s power of suggestion: the stark tonal contrast between the occupied brownstone and its (boarded-up?) neighbours seems to be a commentary on social division and economic marginalization, or perhaps more symbolically, a parable for societal good and evil in and the proximity of these two poles. However, the caption that appears in the 1939 publication of the series complicates such a straightforward interpretation of the photograph: “Built in the mid-eighties for three Rhinelander daughters, the houses at the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and Eighth Street present a rising curve of elegance. Henry J. Hardenbergh, architect of the old Waldorf-Astoria, the Hotel Albert and the Third Avenue Car Barns, designed all three. No. 8 was once the home of the art collection which formed a part of the original Metropolitan Museum of Art.”

The history of the buildings does not reflect the social division that a cursory look might suggest. A related close-up, for instance, shows the grandeur of the marble masonry entrance of No. 8 obscured in this wide shot. We can only speculate on the meaning of the other details not mentioned in the caption: the truck’s company name, the broad and slender water hydrants standing next to a dwarf bus stop sign like the lineup of a comedy troupe, or the spatial connection between the tram tracks, the sewers, and the two cars that bookend this NOHO corner. The original caption by Elizabeth McCausland – recouped by Sarah M. Miller in her recent book Documentary in Dispute – stresses the element of economic privilege even further, stating that the corner brownstone was “the first marble house built in the city,” but also asserts that the moral values represented in the picture are more ambiguous than the bright contrast suggests.

This image has been printed in slightly different ways, as it used to be more common in the past. The Museum of the City of New York, which houses part of the project’s archive, has nine prints of Fifth Avenue Houses, Nos. 4, 6, 8. One of these is a contact print made from the 8x10 inch negative with a distinct sepia tone and less contrast than the enlargements. As such, the potential for the buildings to serve as an analogy for prosperity and hardship gets diminished, a reminder that technique can also define meaning. It’s easy to get lost comparing the different versions of this image in American collections and the variety of their particularities. Some bear a Federal Art Project stamp on the verso; others feature Abbott’s signature and the recto; some are vintage prints, while others were printed as late as the 1980s in a much larger size (20x24 in) by the artist’s estate, etc. From what I can appreciate online, the print at The Clark (pictured here) seems to be the most tonally balanced, although the version in the book is even darker.

I’m interested in how Abbot’s project is unsentimental but not neutral. She tried to convey a resentment for the loss of vernacular architecture and the ways of life that depended on those buildings. Her reputation and biography have become inseparable from the content of those pictures and the history of those sites (for instance, the building on Greenwich Village where Abbott and McCausland lived while making Changing New York is listed in the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project). As the historian Bonnie Yochelson reminds us, “it was her story as much as her photographs that captured the public’s imagination and made her an art-world celebrity.” This amalgamation of art and life has persisted over time, as publications and exhibitions consistently reference the anecdotal dimension of the work, which is now perceived to reflect the artist’s desires with great authenticity. For me, Abbott’s ingenious use of natural light in Fifth Avenue Houses, Nos. 4, 6, 8, and the abundance of details the scene offers articulates her sensitive perception of the urban landscape, resulting in a complex picture in which the elements you see, what they suggest, and what the artist intended them to communicate go in different yet strangely complementary directions. “Pictures”, wrote Abbott, “are wasted unless the motive power which impelled you to action is strong and stirring.” I’m grateful for her intricate motives, which produced a picture so full of life.

SOPHIE CALLE

I am thinking of the video work Voir la mer by Sophie Calle which I saw yesterday at the Musée national Picasso-Paris. Six videos of Istanbul residents seeing the sea for the first time in their lives. They are filmed from behind, looking at the sea. Then they turn around. One of them is very self-conscious in the beginning, looking into the camera.

During the ceasefire in Gaza, the Palestinians were told it was forbidden to go to the sea.

Sophie Calle, Voir la mer, 2011.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

I am thinking of the video work Voir la mer by Sophie Calle which I saw yesterday at the Musée national Picasso-Paris. Six videos of Istanbul residents seeing the sea for the first time in their lives. They are filmed from behind, looking at the sea. Then they turn around. One of them is very self-conscious in the beginning, looking into the camera.

During the ceasefire in Gaza, the Palestinians were told it was forbidden to go to the sea. Among all the atrocities, I still think about that. I can't see the reels of shaking children, I talked about it with a friend here in Paris who told me it was the same for her, but that she knew what was happening without seeing, that she had all the images of the war in her heart without having observed anything. I decided to lean on this faith and instead share other testimonies from the crisis. Like Chris Hedges’ speech about how we are failing the children of Gaza. He cries as he speaks.

I think about the way the Turkish people look into the camera. It reminds me of Kim Hiorthøy's exhibition Jeg er nesten alltid redd (I'm almost always afraid) at Fotogalleriet in 2003. Hiorthøy asked his friends to stand in front of a Super-8 camera for the duration of the roll of film. For three minutes you can look at these people and see all their thoughts, fears and self-consciousness seeping out of them. I think about the fear that we all carry within us.

I am going to a dinner tonight and there has been an email exchange about what to bring. A Frenchman replied that he would bring all his feelings. Me too.

SEIICHI FURUYA

One of the books in my suitcase after my stint at the Polycopies book fair during Paris Photo was Our Pocketkamera 1985 by Seiichi Furuya. After clearing out his attic, Furuya found films from a Kodak Pocket Instamatic camera he had given to his wife Christine in 1978. She continued to take photographs until she took her own life in 1985. This book contains mainly pictures taken by Christine, Furuya and their son Komyo, together with texts written by Furuya.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

One of the books in my suitcase after my stint at the Polycopies book fair during Paris Photo was Our Pocketkamera 1985 by Seiichi Furuya. After clearing out his attic, Furuya found films from a Kodak Pocket Instamatic camera he had given to his wife Christine in 1978. She continued to take photographs until she took her own life in 1985. This book contains mainly pictures taken by Christine, Furuya and their son Komyo, together with texts written by Furuya.

The blurry image of the sliced pineapple on the cover and the portrait of Christine holding the pineapple and looking lovingly at her son, has been on my mind these days as I watch the horrific images of parents holding their murdered children in Palestine. Christine's struggle with mental illness is no secret throughout the book. There is also a striking juxtaposition of image and text that I’m still thinking about, she is standing on a balcony waving to the photographer, and we see many new flower pots on the balcony ledge. This is a still from a Super 8 that Furuya found in 2018. As he writes: ‘She started her life in East Berlin by inviting spring to her home, full of hope for a new beginning.’

Imagine how it must have felt for Furuya to find these films after such a long time. And even more, how it must have felt for their son. Seeing parts of his childhood through her eyes. I think about this when I make this year's album for my daughter, it takes three full working days, and yet there are pictures missing. I haven't figured out how to resurrect my iPhone 5, and I didn't get a chance to back up the last pictures before the phone died. I wonder what pictures are there, pictures of situations I have forgotten, not important to anyone but my daughter and me. In the picture with his mother, Komyo looks at the camera with a half-smile. His mother's arm around the chair he is sitting in, the pineapple ready to be devoured. It may seem like an unimportant, everyday picture, but pictures like these are desperately needed at this time.

LILI REYNAUD-DEWAR

What is it, a naked woman painted in silver print, dancing in the empty halls of Palais de Tokyo? The world is sinking and everyone says that nothing matters except what's happening in Gaza, and I couldn't agree more. And yet I go to exhibitions because art tends to make a difference, art might matter, at least I hope so. I haven't read anything about in beforehand, and am met with a lot of hotel beds and screens above them with men talking, and videos of the artist dancing in the same hall that we're in.

One Image by Nina Strand:

What is it, a naked woman painted in silver print, dancing in the empty halls of Palais de Tokyo? The world is sinking and everyone says that nothing matters except what's happening in Gaza, and I couldn't agree more. And yet I go to exhibitions because art tends to make a difference, art might matter, at least I hope so.

I haven't read anything about in beforehand, and am met with a lot of hotel beds and screens above them with men talking, and videos of the artist dancing in the same hall that we're in. The exhibition is crowded, generations have come to see it. I sit on a bench and watch with a family of three generations. We all smile at each other and at the dancing artist. The grandfather moves a little on the bench so that his leg obscures the projection. He doesn’t notice and none of us mentions it. Somehow it fits that part of the screen has gone dark.

In SALUT, JE M'APPELLE LILI ET NOUS SOMMES PLUSIEURS, Lili Reynaud-Dewar dances, teaches, writes, speaks with friends. The wall text has a dent in it, someone stuck it to the wall and left it there. With the bump. Maybe it didn't matter in the grand scheme of world events. It works as a sign of these terrible times. I read in the text that Reynaud-Dewar wants to examine the function of the artist, and that this second part of the exhibition reads like a diary in which she wants to give an account of what happened inside and outside the Palais de Tokyo (in hotel rooms in Paris, in her emotional and professional relationships, in national and international current affairs).

I go a little further in, sit down on a bed and watch one of the men talking about what it is like to live as a gay man in Paris. I try to listen only to what he says, not read the English subtitles, and I think he stresses that he knows very well that he doesn't live in a utopia, nobody does he says. The elderly lady sitting next to the me says bravo and applauds spontaneously. I raise my hands too. We do not live in a utopia.

PETER WESSEL ZAPFFE

In an envelope from the Asker photo service - dated 18 November (the year is unknown) - found in his study, there were a few strips of positive film that Peter Wessel Zapffe, or his wife Berit, had delivered to re-order some prints. The first photo on the film was taken from the second floor of the house in Asker, depicting the sun setting over Nordre Follo.

Afterimage by Marius Eriksen:

In an envelope from the Asker photo service - dated 18 November (the year is unknown) - found in his study, there were a few strips of positive film that Peter Wessel Zapffe, or his wife Berit, had delivered to re-order some prints. The first photo on the film was taken from the second floor of the house in Asker, depicting the sun setting over Nordre Follo. The next two photos are of the garden. In addition, Zapffe has photographed a class photo from when he graduated from high school in 1918, as well as a newspaper clipping from the time he climbed up into Tromsø Cathedral and proclaimed that he couldn't get any higher with the help of the church. The next time he uses his camera, it's winter. He points the camera at an overgrown, snow-covered garden.

There is a photographic-aesthetic approach to the issues that preoccupied Zapffe. And it is here that the centre of gravity of this book is to be found. His photographic archive is of almost staggering proportions, both qualitatively and aesthetically. I was struck by how Zapffe's pessimistic view of life seemed to crack precisely because of his photographic enthusiasm for magnificent landscapes, towering peaks, family, friends, animals and plants. It is ironic that Zapffe felt that nature's intrinsic value was independent of our participation, when he himself was so present in his subjects. After all, wouldn't the qualities of beautiful and magnificent nature disappear without our presence? Such anthropocentric thinking was far from Zapffe's mind. Perhaps he was not entirely consistent, but the principle was there: The magnificent and the beautiful will not disappear even if man disappears. An uninhabited planet was no accident, he argued.

This is from the book Et Stormkast Vækker Os av Dvalen (A gust of wind wakes us from our slumber) by artist Marius Eriksen. In the book, Eriksen engages in a photographic dialogue with the Norwegian philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe (1899-1990).

LINN PEDERSEN

IT IS A QUIET and early summer morning here in the kitchen. Mari and the boys are still asleep, the girls watching the classic animated version of The Jungle Book in the living room. The sun has been up for a while already, a warm breeze coming through the open window, with the sound of birds. I drink my coffee by the table, watching the city landscape.

Afterimage by David Allan Aasen:

NOTES TAKEN WHILE LOOKING AT LINN PEDERSEN’S Cul-de-sac

Linn Pedersen, Cul-de- sac, 2018 80 x 100cm, giclée print.

IT IS A QUIET and early summer morning here in the kitchen. Mari and the boys are still asleep, the girls watching the classic animated version of The Jungle Book in the living room. The sun has been up for a while already, a warm breeze coming through the open window, with the sound of birds. I drink my coffee by the table, watching the city landscape. Our view spans from Holmenkollen on the left-hand side to the city center and Nordstrand on the right, and I can just catch a glimpse of the fjord above the neighboring rooftop. Not long ago, most of this area was fields and forests. And I think about the fact that we live on top of an old volcano, along the Oslo rift, created some 200–300 million years ago. I imagine the landscape in front of me as pure nature, without the apartment buildings, houses, power lines, cars, and people. Not as the past, but as a future. Only the breeze, the sound of birds, insects, the clouds passing silently by. And then: a rattling in the bushes. A deer stepping out into a clearing, standing still as a statue, with upright neck, its ears rotating, scanning the area for predators.

*

I HAVE BEEN asked to write about an image that is on my mind, and I wonder whether I should go for a photograph by Sally Mann. Or perhaps one of Leonora Carrington’s paintings? There are several to choose from, images that appear from time to time that mean something to me in some way or other. Taking a sip from my cup, I realize I am staring at the work by Linn Pedersen, hanging on the wall beside me. And it strikes me: what about the kind of images that are always in our sight, constantly present, surrounding us in our own home? How do we see them? How do we relate to the few images we have chosen to put up on the wall? Do they become more noticeable? Or do they somehow disappear?

*

LOOKING AT Pedersen’s artwork, the opening line of Tor Ulven’s book of prose Stone and Mirror comes to mind: ‘The monument is a monument to its own oblivion.’

*

IN MAY 2018 Mari and I went to see Linn Pedersen’s exhibition Captain’s Cabin at MELK gallery in Oslo. I had been there a couple of days earlier and seen a work that caught my interest. Leaving the gallery, we agreed to purchase this photographic work, titled Cul-de-sac. We had recently moved into a new apartment, which still had an empty wall in the living room. We thought the photograph would fit that space perfectly. And it did. We kept the work there until the summer of 22. When building an extra wall to make separate rooms for the boys, we had to move it into the kitchen section.

*

WHEN A WORK OF ART is up on the wall, it seems there is no way back. There is a limited amount of money for purchasing art. There is a limited amount of space for placing the art. And there are limits to how often one can replace the art; it is not practical. One might move a table a little to the left or place the chair on the other side of the room, but better leave the art in peace; after all there is a hole in the concrete wall, or a nail in the plaster wall. And besides, the art does not wear out. We sometimes talk about replacing the stained and partly damaged sofa in our living room, but we always conclude that we should wait a couple more years, until the kids are done spilling milk, pizza, and chocolate on it. But how often do we talk about replacing the artwork.

*

DO WE TALK about the artwork at all?

*

GUESTS SOMETIMES COMMENT, saying they are nice pictures. But for us it seems as if the art has become part of the interior, like furniture. I suppose we reflect upon the images in our own way, consciously or not, not feeling the need to share our thoughts on them. It would be like commenting on the shape of a chair.

*

THE ARTWORK, taken out of its original context, is now a natural part the room, integral to the apartment. It seems one tries to make sure the image does not stand out too much. I am not sure that anyone expects the work to mean something to the people inhabiting the room, other than being nice to look at.

*

WE NOW SEE Cul-de-sac during every meal, when drawing with the kids and when reading scripts at night. We see it when we hang out our washing – the laundry rack always placed underneath. In pictures of the children in our family albums, the artwork is often captured in the background. In short, this work by Linn Pedersen has not only become part of the apartment, but it has also become a central part of our life – including, I guess, the subconsciousness of the entire family. I do not know how the children experience the art in our home, but in some way or other they will carry it with them, I am sure, just as I sometimes dream of the pictures that my parents had on the wall when I was a child.

*

THE ROOMS, the furniture, the books, the pictures, the art. A home, a shelter, a place to sleep and eat, to catch one’s breath. A gallery, a permanent exhibition, a place to think, to dream, to view the world from.

*

I LOVE THE COLORS of Cul-de-sac. And I like the shapes and forms, the bends spiraling downwards, bringing the whole image, basically calm and quiet, into motion, as if painted with large brush strokes from top to bottom. A photo taken in daylight, I guess, but presented in a kind of ghostly, dreamlike state: the inverted colors making the vegetation white, almost like frost, a background of ice holding the entire structure in place. From one point of view, it looks like a very specific sculpture. From another point of view, it is almost abstract.

*

I COULD SIMPLY SAY the image is nice to look at. That it is striking and beautiful. And leave it at that. But wait a minute. Take a closer look. The image deepens, the meaning expands.

*

HOW DID I experience the work when seeing it for the first time? Surely not with an analytic gaze. I was caught up in the mood of the exhibition, and then this image stood out.

*

A SCULPTURE, a ruin, an ominous warning.

*

IT SEEMS like a coincidence picking an artwork, regarding all the images one comes across during one’s lifetime. We see an image. We like it. The timing is right. We have some extra savings. We bring the work home. It becomes the image we see every day. It becomes decorative art. An image from which the message, meaning or mood slowly merges with the rest of the interior. The image lingers in the background, until – like now – it sort of reappears. And reminds me of something.

*

THIS IMAGE reminds me of something. Or perhaps it is more of a feeling, not a memory at all. It might even be quite the opposite: it might have to do with the future. Not a feeling, but a premonition.

*

‘WE ARE JUST a moment in time,’ laments Vincent Cavanagh of Anathema. ‘A blink of an eye. A dream for the blind.’

*

ALL THESE SONGS and all these voices, always present, ready to burst out. A song is not a memory. It is a presence. Voices always singing, though often muted, until some association turns up the volume.

*

‘TIME IS NEVER TIME at all,’ sings Billy Corgan of The Smashing Pumpkins. ‘You can never ever leave, without leaving a piece of youth.’

*

ONE LIKES the image; one brings it home.

*

TOR ULVEN´S STONE AND MIRROR is organized partially as a kind of exhibition, the texts having subtitles like 'still-life,' 'installation,' 'landscape,' 'sculpture,' 'ready-made' and 'archeologic field.' The works in Captain’s Cabin could be divided into similar categories. In a sense we are invited to a museum. We are given the opportunity to see our own age as something of the past.

*

MARIT EIKEMO’S book of essays, Contemporary Ruins, also comes to mind: the feeling of walking through the remains of constructions and buildings recently built, some of them not even finished, but already on the verge of being forgotten, bits and pieces our own communities, stories and knowledge slipping unnoticed into history.

*

I REMEMBER something now. Some of my own photographs from the 90s. One of a car wreck, another of an abandoned house, a third of a boat in a field, covered by grass. Looking at Cul-de-sac now, these amateurish images suddenly become meaningful. I see something in them I did not think about before.

*

THE MOOD of Captain’s Cabin, the combination of methods – black and white images, images inverted to negative, filters, underexposures – brought me into a state of wonder. The way houses, cars and boats were presented, created an otherworldly atmosphere, a feeling that Earth had been abandoned a long time ago. I was turned into a sleepwalker among the objects, buildings, and playgrounds, I found myself staring at strange landscapes and signs of a civilization past, nothing left but these machines and constructions, partially taken over by nature. A vision of our time depicted from a future position. I felt the distance to here and now.

*

I WAS TAKEN somewhere beyond the catastrophe. I sensed a great silence. And almost felt I had to whisper, as we moved from image to image.

*

ULVEN: 'Your own voice // on tape / it is / the reflection / that reveals / that you too / belong to // the Stone Age.'

*

I LIKE THE FACT that we get to look at art while hanging up the laundry or eating tomato soup.

*

THE THEMES and feelings that arose in the larger context of Captain’s Cabin, what I would summarize as a dark and poetic depiction of an abandoned world, are central to the work Cul-de-sac itself.

*

GROWING UP in the 80s in the rural landscape of Leirfjord, Nordland, my friends and I discovered small landfills and other remains of the past. Behind a cluster of trees, a heap of wrecked cars kept our attention for days. We played in them, broke the windows, brought parts home. We ripped off the springs from an old sofa and tied them to our shoes, and thus inventing super jump boots. We set up an orchestra, mainly consisting of percussion, beating the rusty barrels with sticks. On a fishing trip to a lake up in the mountains, I followed an overgrown path, and came upon an old house, abandoned probably a couple of generations earlier, now threatening to collapse. The sense of history and times past fascinated me, took hold, and I would later, as a student, return to take pictures of the old house and the cars. I probably did not have a clear purpose at the time, bringing my camera for a walk in the places I had been as a child. But when I look at the pictures I chose to take, I realize that there are only various ruins and other remnants of human life in the midst of nature.

*

ALL THESE THINGS are gone now: the cars, the landfills, the house, probably removed for safety- and environmental reasons. The only traces left are the photos on my hard drive. The hard drive itself will of course end up in a dumpster somewhere, the monuments of the past themselves forgotten.

*

THE HARD DISK as a brain, filled with images, potential memories.

*

WHEN MY 2022 hard drive crashed last year, some of my favorite shots were trapped inside it, among thousands of other images. At the time I couldn’t afford to recover the files, so I just stored it my wardrobe drawer instead. It is still in there, safely wrapped in plastic, and in a sense, it is a relief. All those pictures, all those memories, all those details. Do I really need them?

*

HOW MUCH are we supposed to remember?

*

TAKING PICTURES almost every day, my own project has revolved around keeping track of time, documenting the daily events in our children’s life. To keep up, I force myself to organize and edit photos each night. I spend as much time with my camera and my images as I do without them. And while the intention has been to understand time better and somehow getting closer to the children growing up, I have instead experienced the quite opposite: a mild confusion or a misconception about the events, how they happened, where and when. The harder I try to grasp time the faster it slips through my fingers. And when printing images or receiving my albums in the mail, I often think, with a naïve disappointment: is this all there was to it? Is this all that happened?

*

WOULD I HAVE understood more just participating, being present? Or by writing a diary instead of taking photos?

*

STILL, I KEEP taking pictures. An obsession. A fear of missing out.

*

I SOMETIMES imagine the girls only see my face as a camera, and that they dream at night of this black camera lens chasing them around.

*

THERE ARE TIMES when I think of photography as destructive and as an unnatural way of looking at the world and remembering it by.

*

I GUESS I TAKE the pictures for myself. It has become a habit, or an addiction. And sometimes I recall, a little shameful, what Sontag wrote: 'Using a camera appeases the anxiety which the work-driven feel about not working when they are on vacation and supposed to be having fun. They have something to do that is a friendly imitation of work; they can take pictures'. But of course, I also wish for the children to have the pictures one day, having the opportunity to leaf through their early years, just as I did with mine. Still, I wonder if the large number of photographs displaces real memory. If so, it really is a paradox if we think the photograph is meant to preserve a memory. And by the way: What memory? Whose memory? To what purpose?

*

WHEN THE LINE between looking and taking a photo becomes blurred.

*

A PHOTOGRAPH is always somewhere between a window and a mirror.

*

IN METTE KARLSVIK’S novel Darkroom, the protagonist, addressing her father, says: 'My sister and I have lots of photographs to remember our childhood. We do not have just one picture, or a handful, like you have: You have the picture from baptism, a class picture from school, and one from college. My sister and I have albums and walls covered with memories. We get a more nuanced picture of our childhood. Or do we let our memories become more shaped by photographs than your memories are.'

*

IF YOU HAVE only one photograph of yourself as a child, does your life seem poorer or richer, your memories more or less valuable?

*

A COUPLE OF hundred years ago there was no other way of recalling one’s past except through stories, drawings, objects, and other 'natural' ways of remembering. I imagine people recall their relatives and friends as voices, talking, crying, laughing, or singing. Always there, always present.

*

I TRY TO imagine a modern society like ours, only without cameras, mobiles, and photographic images.

*

MY CHILDHOOD FRIENDS and I experiencing the world by just being present.

*

PHOTO ALBUMS as personal ruins.

*

WHEN I AM in doubt, Mari tells me I must keep taking the pictures, that it is worth it, that I should not feel bad about it. The girls will appreciate it one day. And I am all good to go again.

*

AND BY THE WAY, I am not sure if preservation of memory is what interests me in family albums. I think it is about placing oneself in time and in a context, being able to tell a story, make connections, finding one’s place in the world. And this is something worth passing on. An image as a starting point from which to tell one’s story.

*

PHOTO ALBUMS as mirrors.

*

WE LOOK AT the art on our wall and see something. The years go by. We look again and see something else.

*

I REMEMBER a painting from my early childhood. I thought it was a picture of my father and my older brother and sister. When rediscovering the painting, twenty years later, I realized the characters had no relation whatsoever to my family.

*

CHILDREN INTERPRET art the same way adults do: with their own frame of reference.

*

I SHOULD ADD: My parents still have that same picture on their wall. Moving from apartment to apartment, from house to house, they always kept the same images. Some disappeared in time, the rest were kept. The pictures at my parents’ house reminds me of the rooms we have left behind. The pictures on their walls evoke memories of my early childhood in Sweden.

*

THE ROOM contains the picture, and the picture contains the rooms. We never travel very far; the past is always right by.

*

MARI’S PARENTS became friends with the French-Polish painter and printmaker Tomasz Struk in the 70s. They bought several of his prints, had them framed and put up on the walls in their house in Homme, Vigeland. They even bought more prints than they had room for, as a way of helping him out, and then passed these on to friends and acquaintances. Today the art of Tomasz Struk in Norway is therefore heavily concentrated in the Mandal area. When Mari moved to Oslo into her first apartment, she brought a couple of prints. And now, years later, Struk’s prints have ended up on our walls. Mari says that the pictures carry some of her childhood with them. And I feel that, in some way I am taking part in it, seeing what she has seen.

*

IN MY VIEW Cul-de-sac primarily deals with what remains, showing how the most familiar objects grow mysterious with time. While the theme of mortality is inherent in all photographic work, Pedersen’s image not only addresses this theme more explicitly, but raises some important questions as well.

*

THE ARTWORK as a mirror. Me sitting here, looking at myself.

*

THERE WAS A SENSE of abandonment in the series of images in Captain’s Cabin, emphasized by the depopulated scenes and scenarios. This sense is even more notable when the one image is taken home. The separate works communicated with one another, perhaps about their collective abandonment. Now this work hangs all alone on the kitchen wall, mumbling monotonously. I am sure it is some kind of warning.

*

OR THE IMAGE, presented with inverted colors, might simply be showing a water slide after closing time. As Ragnhild commented, when visiting: Cul-de-sac made her think of someone she met once who had broken into an abandoned amusement park at night.

*

OR IN THE PERSPECTIVE of the 'exhibition,' the slide as a gigantic object in an outdoor museum, framed by a fence: 'Do not touch the art.'

*

A POST-APOCALYPTIC IMAGE, a contemporary ruin, a comment on society, Cul de sac as metaphor for a difficult situation, the peak of our civilization as loss of perspective and meaningless entertainment, 'amusing ourselves to death', or just a playful piece of art.

*

THE SERIOUS themes contained in Pedersen’s image is, I think, paired with a sense of humor, or at least an absurd dimension. We could see the title of the work quite literally: for what is a water slide except a dead end?

*

HAVING WRITTEN my master thesis on Tor Ulven, and for years read his texts, his images appear in my mind from time to time, like now, looking at Cul-de-sac. And even though they are literary ones, I find them just as vivid as any visual artwork. I could as well have written about one of his literary images.

*