BJARNE BARE

Once upon a time some Western-oriented theorists spoke of Platform Capitalism.

We know what a platform is.

The difficult question: What is capitalism?

Many different answers have been formulated.

The most comprehensive and pertinent of all answers is the following:

Capitalism is an attempt to attain eternity, the only attempt that has ever succeeded.

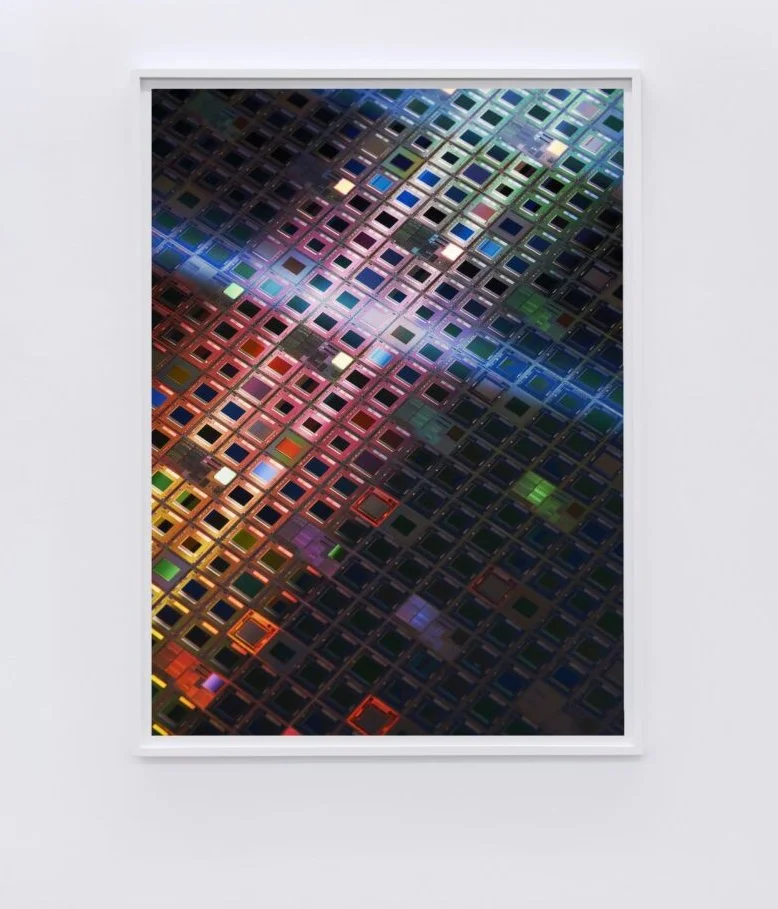

From the exhibition Latent Eclipse, Bjarne Bare, OSL Contemporary.

Afterimage by Franco “Bifo” Berardi:

Abstraction, eternity, and despair

A personal introduction to the poetical world of Bjarne Bare:

What was expected to happen has happened already.

What will happen next is inscribed in the intimate texture of what has already happened.

What we have long feared would happen, has happened since the beginning of time.

But we were not aware of the extent and of the depth of the damage.

Now we are obliged to acknowledge the truth, because oxygen is starting to run low.

What we want is irrelevant. And also what we are is irrelevant, at this point.

“We” is no more, and I don’t feel so well this morning, because quantum computers may solve in minutes what could take today’s supercomputers millions of years to calculate.

Once upon a time some Western-oriented theorists spoke of Platform Capitalism.

We know what a platform is.

The difficult question: What is capitalism?

Many different answers have been formulated.

The most comprehensive and pertinent of all answers is the following:

Capitalism is an attempt to attain eternity, the only attempt that has ever succeeded.

Capital is abstraction from life: life turned into abstract value. Abstraction is not in time. Therefore it is eternal.

Nothing human has been eternal so far. However in the quantum dimension we have now managed to complete the most coveted mission since the dawn of time: abstraction is not in time.

The eternity of our artifact has been made possible at the price of the death of our irrelevant souls.

Technically speaking what you see is a “cryogenic stack”. Some engineers call it “the chandelier”.

It doesn't matter what it looks like. It may seem archaic because it is eternal.

It may seem futuristic because it is eternal.

It is eternal because it is timeless.

Eternal ice is melting, as you know, so ice is no longer eternal, because ice was material and all that is material melts in the timeless air of abstraction.

Indeed, the (true) eternity of capital entails the melting of (falsely) eternal glaciers and the rapid extinction of the biosphere. The biosphere is dying, and it is largely extinct, at this point.

Also, the termination of human animals is approaching. Everybody knows, more or less, but nobody is noticing.

Nevertheless, a polar bear is slowly moving through eternal ice, because Art is immortalizing dead things, like ice and bears.

And the market is immortalizing dead Art, which in turn implies the eternity of Art.

What was expected to happen has happened already.

Do you see human beings around?

You don't see human beings because they have been exterminated by the biblical infection.

Do you hear human voices in the surroundings?

You don’t hear human voices because they have been drowned out by white noise.

Lucy in the sky with diamonds is not human, of course.

She’s cryogenic. Timothy Leary started thinking about cryogenic eternity thirty-five years ago, while preparing to die.

The cremated remains of the LSD aficionado, along with those of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry and 22 other people, were blasted into orbit from the Canary Islands along with a Spanish scientific satellite.

Each person's cremains, as they are called, are socked in a lipstick-sized capsule expected to circle Earth. The flight cost is: $4,800 per ashtronaut. The price is "comparable to most conventional funeral services," according to Celeste Inc., the Houston-based firm that contracted to have the ashes sent space-ward.

But wait, there's more: Celeste says that the cremains, each of which weighed 7 grams at launch, should make at least 8,600 orbits before reentering Earth's atmosphere in a second, consummate cremation.

"Space remains the domain of a few, the dream of many," Celeste Vice President Charles Chafer said in a statement.

The Earthview space flight, on the other hand, he says, offers "a final chance to become part of the universe, by being one with the universe." A sentiment with which Leary would, no doubt, agree.

Lucy in the sky with diamonds is the implementation of that old dream.

The Erscheinung of Ex-istenz. And the becoming nothing of the Erscheinung.

Roughly 90% of all modern-day semiconductor devices use material derived from the Czochralski method, also Czochralski technique or Czochralski process, a method of crystal growth used to obtain single crystals (monocrystals) of semiconductors (e.g. silicon, germanium, and gallium arsenide), metals (e.g. palladium, platinum, silver, gold), salts, and synthetic gemstones.

Lucy in the sky with diamonds is the crystallization obtained from this process.

Lucy is located in France, Euro-Q-Exa is located in Germany.

Will they meet at some point in the future?

What a stupid question.

Why should they meet?

They do not feel sexual attraction, even if Lucy is quite sexy. She is as sexy as a piece of ice.

You can see her flying over the eternal ice already melted or in the process of melting.

What used to be solid melted in the air, while what used to be living is turning dead, and what used to be abstract has taken over all life.

This is my approach to the poetics of a crystallized (lucid, sparkling, translucent) artist called Bjarne Bare whose works are (eternally) exposed in a gallery in the city of Oslo.

In addition to our weekly Afterimage column, we share this text written by Franco “Bifo” Berardi for the exhibition Latent Eclipse with Bjarne Bare, currently on view at OSL Contemporary.

JAMES VAN DER ZEE

There are many aspects of this photograph that draw me to it. I like to think about the process of looking. When I look at something, I follow my feelings. I want what I see to move me, usually in a layered way. I also want complexity, because it makes me want to look longer and reflect. When I looked at this picture again, I understood why I loved it so much—it resonates with my subject matter. Looking at it now, with my 45-year-old eyes, in a world burning in many ways, and with a deeper understanding of myself and my work, I realize that this photograph makes me feel safe. In a time when everything feels confusing, this photograph feels clear—like a statement. I feel devoted to it. I admire it. I feel included in it, and I feel protected by it, with a sense of safety.

James Van Der Zee, Couple, Harlem 1932, © 2026 Estate of James Van Der Zee. www.moma.org Acquired through the generosity of Richard E. and Laura Salomon.

Afterimage by Nydia Blas:

I think it’s my all-time favorite photograph. When I was asked about Afterimage, this came straight to my mind. It feels like it’s been in my head forever, but I probably became more familiar with it during graduate school in 2013. By chance, I realized that I had taken a photograph that kind of spoke back to this one, without realizing they were in conversation. That moment of connection is one of the reasons I’m drawn to photography in general: its ability to speak across generations and time, still remaining relevant. Everything we’ve ever seen is somewhere in our minds, and we never know when we might reference it, be reminded of it, or recall it creatively. That’s one of the things I find fascinating about photography. I’ve never exhibited this photo.

I’m from New York, and in 2016, while visiting Atlanta—where I now live—I was at the High Museum. I turned a corner and saw this photograph in a frame. It surprised me to encounter it in person after having seen it so many times on a screen. That was a beautiful moment. The image doesn’t change, but we do in relation to it. I have changed and grown since I first looked at it. Even my worldview and thoughts are constantly expanding. It’s interesting to think about time: the photograph was taken during an important, powerful, and moving period, yet we find ourselves in similar moments again.

There are many aspects of this photograph that draw me to it. I like to think about the process of looking. When I look at something, I follow my feelings. I want what I see to move me, usually in a layered way. I also want complexity, because it makes me want to look longer and reflect. When I looked at this picture again, I understood why I loved it so much—it resonates with my subject matter. Looking at it now, with my 45-year-old eyes, in a world burning in many ways, and with a deeper understanding of myself and my work, I realize that this photograph makes me feel safe. In a time when everything feels confusing, this photograph feels clear—like a statement. I feel devoted to it. I admire it. I feel included in it, and I feel protected by it, with a sense of safety.

When I think of James Van Der Zee, a photographer popular during the Harlem Renaissance, I appreciate how he created a record, or counter-narrative, to the stereotypes about Black people at the time. In his photographs, the subjects—most often Black Americans—and the locations and clothing (what I like to call costumes) serve as markers for other things, like status. The car functions as a prop and feels powerful because it takes up almost the entire frame. It cuts through, making the subjects important. They feel safe. The light is very soft, and the car door is open just enough to welcome me into that space. These people seem to be inviting the viewer into an important space.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite different people to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

JEAN ROUCH

Images from the film Les maîtres fous by the French filmmaker and anthropologist Jean Rouch have been on my mind recently. I find Rouch interesting because he started as a documentarian making anthropological films but later began making ethno-fiction. In Les maîtres fous, as far as I know this film is documentary, participants enter trance-like states in ritual performances in Ghana, where they dress as colonial authorities, mimicking their gestures and violence, while also channeling spirits.

© Jean Rouch, Les Maîtres fous, 1958. Les Films de La Pléiade

Afterimage by Tiago Bom:

Images from the film Les maîtres fous by the French filmmaker and anthropologist Jean Rouch have been on my mind recently. I find Rouch interesting because he started as a documentarian making anthropological films but later began making ethno-fiction. In Les maîtres fous, as far as I know this film is documentary, participants enter trance-like states in ritual performances in Ghana, where they dress as colonial authorities, mimicking their gestures and violence, while also channeling spirits. They sometimes imitate dogs—crawling, barking, and howling—and actual dogs appear in the ceremonies, adding to the chaotic, transgressive energy. The performances are a mix of possession, music, dance, and symbolic reenactment, creating a visceral exploration of power, oppression, and ancestral memory.

The images I am thinking about are very context-driven, as I am currently preparing to go on a small residency in São Tomé e Príncipe to shoot a film, curiously, in part about dogs.

Portuguese sources from the time state that it was an uninhabited archipelago, and that the Portuguese used it to grow exportable crops and as a testing ground and base for the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. As with any colonial enterprise at the time, it became, I think for centuries, one of the biggest producers of coffee and chocolate in the world.

The people who were sent there were mainly from Angola (another former Portuguese colony), and in smaller percentages from places like the Congo. I read somewhere that in Haiti there was a similar Central and West African population. Maybe that is why you find similar African syncretism, akin to voodoo, in São Tomé e Príncipe, much like in Haiti. Coincidentally, alongside Haiti—and I don’t know which came first—these were the only two places in the world where there were slave revolts that managed to take over and form their own communes.

São Tomé e Príncipe also has a unique cultural tradition called Tchiloli, a public theatrical performance combining music, dance, and drama, rooted in a 16th‑century Portuguese play about Charlemagne, adapted and creolized over the centuries. Performers wear colonial-style costumes and masks, creating a symbolic cultural tradition. It is kind of eerie: people who are descendants of slaves and colonized peoples putting on the white face, carrying the memory of a centuries-old ritual, metabolizing and transforming a tradition that started with their colonizers.

This performative aspect and the ritualized mimicry reminded me of Les maîtres fous. I’m not sure the conceptual depth translates in a still, but I haven’t been able to shake that film ever since I saw it.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite different people to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

SZILVESZTER MAKÓ

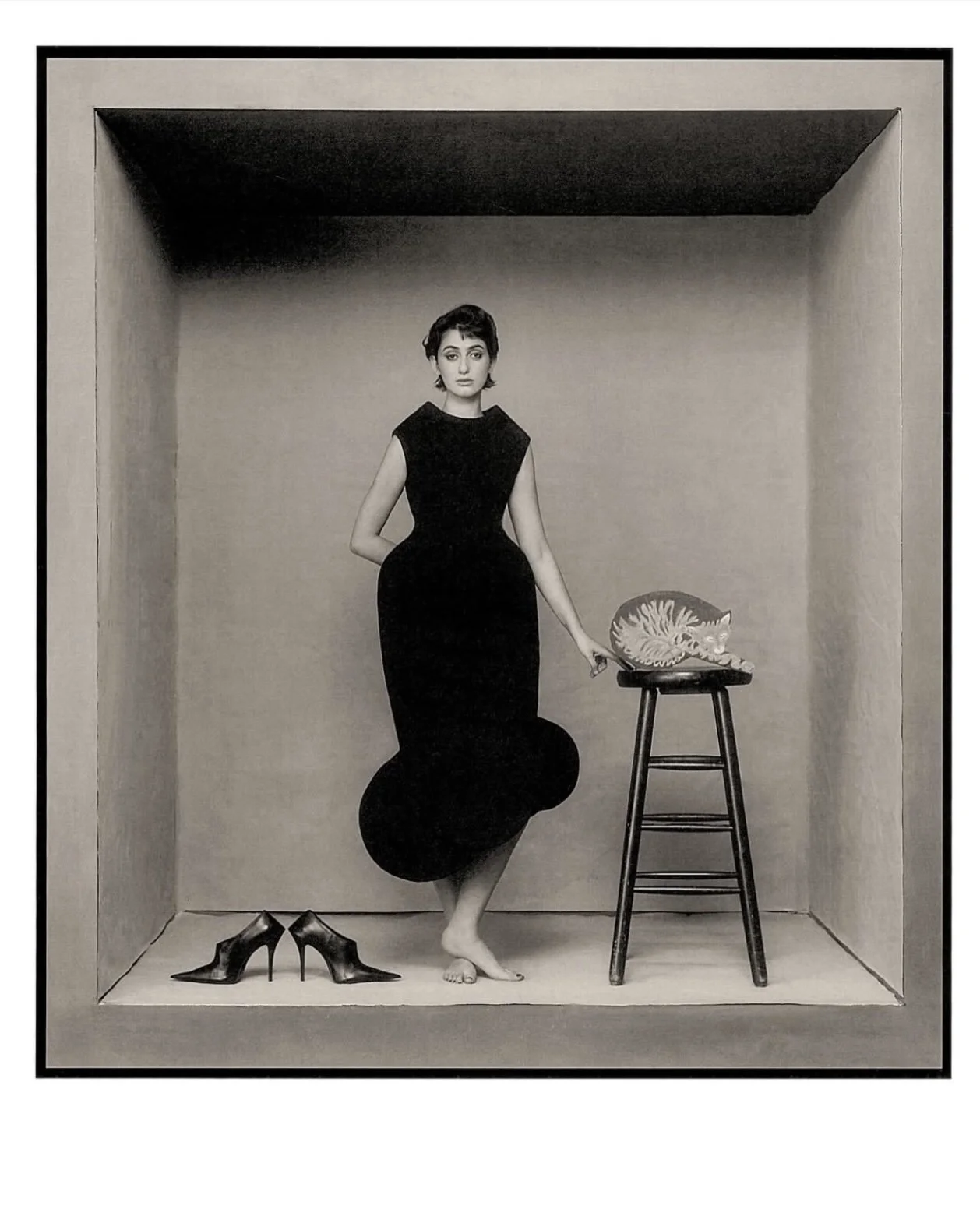

What is this? Is it a glimmer of hope we can spot in the series of photographs accompanying the interview with Rama Duwaji in The Cut? Shot by Szilveszter Makó, the portraits of the Syrian illustrator and animator, wife of the new Mayor Zohran Mamdani, referred to here as the ‘First Lady of New York City’, seem like small life boats floating in the dark sea of the States. They playfully evoke classic fashion photographs of the 1940s, as well as the Surrealist paintings of René Magritte. I love this one, with her standing barefoot, her shoes placed on one side and a painted sleeping cat on a bar stool on the other. Her posture, her firm gaze …

Szilveszter Makó for The Cut, with Rama Duwaji. Published in The Cut (online/print).

Afterimage by Nina Strand:.

What is this? Is it a glimmer of hope we can spot in the series of photographs accompanying the interview with Rama Duwaji in The Cut? Shot by Szilveszter Makó, the portraits of the Syrian illustrator and animator, wife of the new Mayor Zohran Mamdani, referred to here as the ‘First Lady of New York City’, seem like small life boats floating in the dark sea of the States. They playfully evoke classic fashion photographs of the 1940s, as well as the Surrealist paintings of René Magritte. I love this one, with her standing barefoot, her shoes placed on one side and a painted sleeping cat on a bar stool on the other. Her posture, her firm gaze … these are the kind of images we need while the rest of her country and so much of the world descends into free fall. The president hasn't even finished his first year in office, there are three more years to go, and so much is already broken.

Over the holidays, I read the text about photographer Donna Gottschalk by Hélène Giannecchini for the show Nous Autres at Le Bal, Paris. Gottschalk grew up in in Alphabet City, New York, in the 1950s, and Giannecchini reflects: 'The people she loved most lived on these streets, and most of them are long dead. And it’s the brutality of this city, of society as it is, the relentless poverty, everything that weighs on marginalized bodies, that killed them.' And today, all bodies that are not white male bodies seem in danger, like the woman with the last name Good, just killed by ICE in Minneapolis.

Over the past year, I have collaborated with two female photographers, Carol Newhouse and Carmen Winant, observing them creating double exposures, a technique Newhouse learned while living in a lesbian separatist community in the United States during the 1970s. They used photography as a tool to reinvent themselves. They had abandoned their families and everyday lives and built their own homes in the woods of Oregon. They were safe there. They were unsafe in the city. The houses are still standing, and I wonder if the women might feel tempted to move back there as they witness history grimly repeating itself for the queer community in the States.

Maybe we should all leave society? Or we could move to New York, where the powerful wheels of Mamdani and Duwaji are turning, there is hope. In the photo series, Duwaji’s confident gaze and half-smile bring a sense of sanity and control. Scrolling through her illustrations on her website gives even more, with the drawing of three fierce women of different races surrounded by flames. The one in the centre has her arm raised in a fighting pose as a text promises: 'Sooner or later, people will rise up against tyranny.’

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite different people to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

CAROL NEWHOUSE & CARMEN WINANT

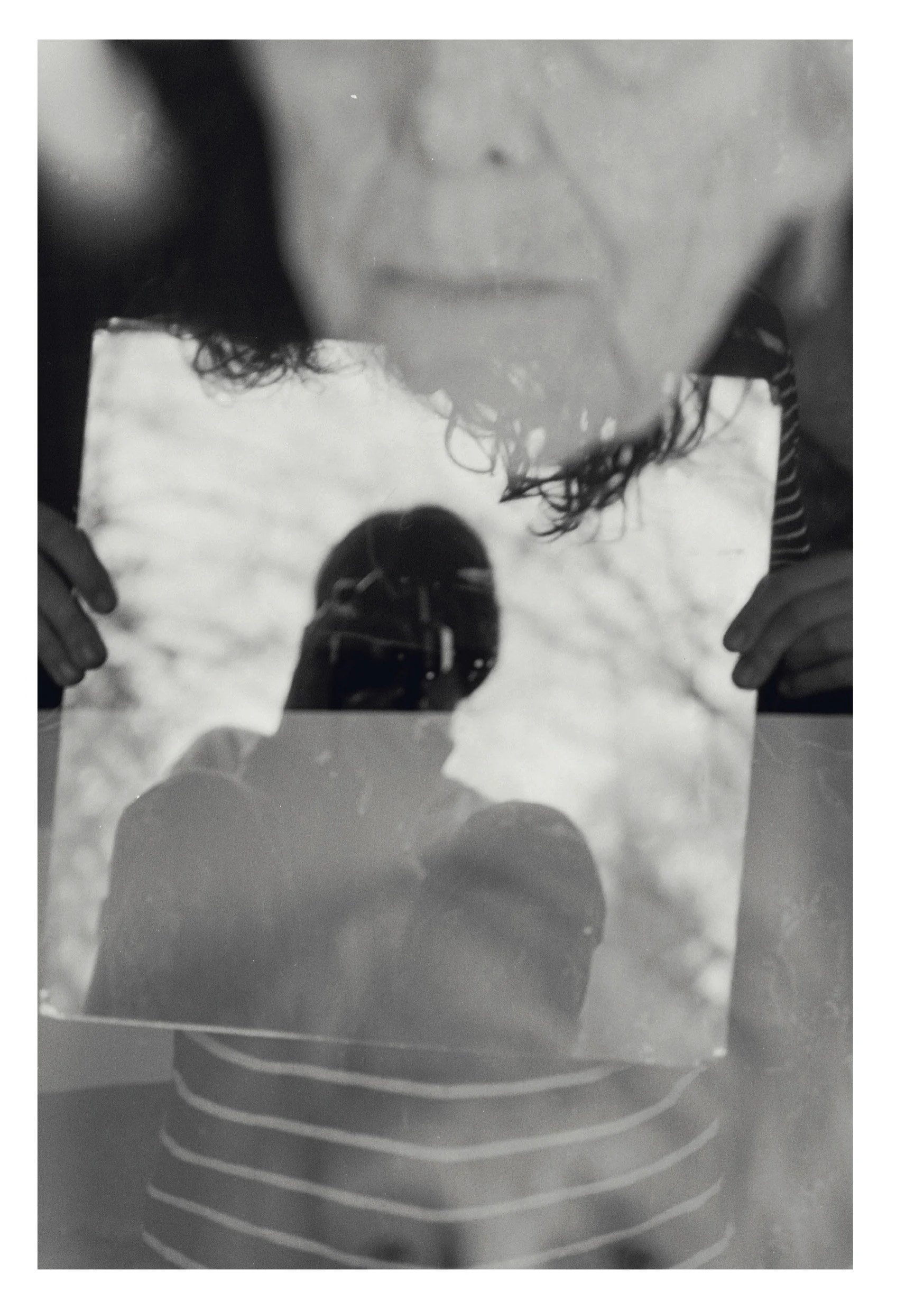

The mirrors in Double are hidden among the other works, aiming to include the viewer by having them unexpectedly catch sight of themselves, perhaps noticing something about who they are. For the artists, the mirrors also function as a material reference. There are many mirrors within the pictures from the old Ovulars that placing them on the outside creates a kind of double exposure—a doubling in itself.

Double Carol Newhouse & Carmen Winant, Les Rencontres d’Arles, 2025..

The mirrors in Double are hidden among the other works, aiming to include the viewer by having them unexpectedly catch sight of themselves, perhaps noticing something about who they are. For the artists, the mirrors also function as a material reference. There are many mirrors within the pictures from the old Ovulars that placing them on the outside creates a kind of double exposure—a doubling in itself.

As Carol points out in an email: ‘In that moment, it can feel as though the three of us—the viewer, Carmen and I—are held together in the same instant, captured in the same image. It’s instantaneous, like the click of a shutter or the glance of an eye. It is also intergenerational, echoing the passage of time.’ Carol sees this as an inclusive encounter that suggests movement and the potential for freedom and creativity: ‘To me, all of this describes the female gaze, which I could also call the feminist gaze.’

(…)

Carol shares a thought about how she never anticipated how her work in the 1970s—those ideas and images—would eventually find their way into the world. The footage and the creative process had never seemed as if it would last beyond the moment; the women hadn’t been thinking about the future, just doing what felt right at the time. Now, years later, people are still asking her what they were thinking when they made their work. The fact that it continues to resonate with so many is a surprising reminder of how far it has travelled and how deeply it has impacted others. It was serendipity that led Carmen to rediscover this work almost a decade ago, bringing it back into the light through her book and the several shows she’s curated with Carol. Their ongoing conversations around using photography as evidence led to this one-year workshop where together these two friends have created new narratives. As Carmen later writes, there is poetry in the fact that their pictures and stories have quite literally merged on celluloid.

The photographic works from the Ovulars explore the construction of histories, as well as the significance of the photographs themselves—images designed to challenge the existing power structures within the medium. The double exposures created by Carmen and Carol are part of this lineage, contributing to an ongoing feminist photographic movement. Their work not only reflects history but actively reshapes it.

This year has been an incredible one for Objektiv Press and our Afterimage series. As we wrap up 2025, we’ve been sharing excerpts from our books every Monday leading up to Christmas. We leave you with these words from Double by Carol Newhouse & Carmen Winant, Objektiv #30. We’ll return next year with more. Until then, we wish you moments of peace and connection.

MARTIN PARR

My autoportrait project has run over 40 years. The aim is to demonstrate the different ways in which you can have your portrait done in a studio or public space, as well as the different techniques photographers employ. The only reason I use myself as the subject is because I’m the one person who’s consistently there. Hanoi Studio took five black and white shots of me in different poses, and in one they gave me naff sunglasses. They then did a montage, printed in black and white, and hand-coloured.

Martin Parr/Magnum Photos

My autoportrait project has run over 40 years. The aim is to demonstrate the different ways in which you can have your portrait done in a studio or public space, as well as the different techniques photographers employ. The only reason I use myself as the subject is because I’m the one person who’s consistently there. Hanoi Studio took five black and white shots of me in different poses, and in one they gave me naff sunglasses. They then did a montage, printed in black and white, and hand-coloured.

I’m uninterested in how I look, as long as I’m presentable. I look in the mirror once a day – I have no choice, as I’ve got to comb my hair. I guess that’s interesting given I do fashion photography. I’m not interested in clothes, I just wear what’s comfortable. Socks with sandals is a good combination before it gets to the hottest part of the year. I guess you could call it my spring look …

I have had a wonderful life with photography. From North Korea, to a vicar’s garden party in Somerset, or shooting Mar del Plata beach in Argentina – what a privilege it has been to see the world and record my response. I had a funny one in Morecambe last summer. I was taking photos and this couple came up and said, “That’s a nice camera. What are you doing around here?” I replied, “I’m documenting Morecambe.” They said, “You mean like Martin Parr?” I said, “I am Martin Parr.” They were rather surprised.

I’ve been taking photos for almost 70 years, and in that time we’ve seen the amazing transformation from analogue film to the digital era, and I’ve got a lot older. We live in a difficult but inspiring world, and there is so much out there I want to photograph.

This week’s Afterimage contribution is an edited extract from Utterly Lazy and Inattentive by Martin Parr and Wendy Jones, published by Penguin. It is adapted from “There’s Something Very Interesting About Boring”: Martin Parr on His Life in Pictures, The Guardian, 24 August 2025, in remembrance of Parr following his passing this weekend.

ELLE PÉREZ

When we were developing my show Diablo at MoMA PS1, the curators were interested in doing something that evoked the feeling of being in my studio. The collage Diablo was originally not meant to be an artwork, but was my answer to the question 'What does your studio look like?'

Diablo is a version of one of my foundational impulses: I have always made this kind of image collection, even as a kid.

From Elle Pérez Diablo, MoMA PS 1.

2024 On the wall collages

When we were developing my show Diablo at MoMA PS1, the curators were interested in doing something that evoked the feeling of being in my studio. The collage Diablo was originally not meant to be an artwork, but was my answer to the question 'What does your studio look like?'

Diablo is a version of one of my foundational impulses: I have always made this kind of image collection, even as a kid. An intense collage covered an entire wall in my childhood bedroom. I was surrounded by images and pieces of text for years, and I’ve made something similar in every studio I’ve had. The wall collages that I make in my studio are an engine for moving my work forward, and for discovering potential formal innovations. I have become interested in these collages as works of art because of how they reflect the process of thinking with images. They both trace and make possible the development of thought, using the multiple and mundane materials of the studio: laser prints, inkjet prints, darkroom prints, reference articles, screenshots, work prints and postcards, Post-It notes, washi tape, and push pins.

The collages reflect the honesty and idealism of the studio space, a place of thought unbounded, where the question to answer is: What more is possible? In these collages made as studio work, I am able to conjure possibility while it is still not yet within my grasp; manifestation and failure to arrive both live within these pieces. A gift of vision that I give to myself.

I’m interested in the movement of the pieces of paper as a gesture. Catching the light and the breeze, the papers are not fixed in place except for at one or two points. They are animated by their relationship to space and open air; a passing person’s wake could lift the page. My drive toward making both these collages and also observational images feels deeply connected to being from places that are always about losing, reimagining, and forgetting.

Reimagining is one of my greatest skills. I think it comes from that experience of constant loss: you can’t hold onto things forever; you have to keep moving, reshaping, and finding new ways to see things. It’s that cycle of loss and reinvention that shapes how I approach the world, especially through photography.

This year has been incredible for Objektiv Press and our Afterimage series. As we wrap up the year, we’ll be sharing excerpts from our books every Monday leading up to Christmas. This is Elle Pérez from their book the movement of our bodies, Objektiv #29.

DAVID CAMPANY

I have been thinking a lot lately about the relation between ‘theory’ and ‘writing’, and ‘literature’. Many theorists don’t think of themselves as writers, and of course many writers don’t think of themselves as theorists. As we know, a lot of ‘theory’ is not very well written, probably because those who write it do not think of themselves as writers.

I have been thinking a lot lately about the relation between ‘theory’ and ‘writing’, and ‘literature’. Many theorists don’t think of themselves as writers, and of course many writers don’t think of themselves as theorists. As we know, a lot of ‘theory’ is not very well written, probably because those who write it do not think of themselves as writers.

The essayist and psychotherapist Adam Phillips once suggested that psychoanalytic writing, from Freud onwards, but particularly Freud, should be read as a form of literature. That is to say, not as a claim to truth or science, but as a claim to writing. Asked for a definition of literature, Susan Sontag suggested it was writing that you would want to reread.

I read a lot of theory, but the only theory I reread are the texts I want to reread, and these I think of as also being literature. However, I would like to think that I have a wide sense of what literature is, and can be. When reading, I keep my mind open for those unpredictable moments when a theoretical idea finds what seems to be a fully satisfying, or startling, or at least profound literary form.

People often complain about the way certain writers still seem to dominate theoretical discussions of photography, particularly Walter Benjamin, Roland Barthes, and Susan Sontag. I share that frustration. But do you know why their thought dominates where the equally profound thought of others does not? It’s because it was well written. Their writing stays with people as sentences, as modes of thought that found compelling written form, as literature.

Rereading a text has its own satisfactions. Not the least of these are the fact that we never read it the same way twice. In rereading, the emphasis, our emphasis, may fall somewhere else. In this sense, to reread a text is to measure one’s own changes – intellectual, social, political, aesthetic, critical, poetic – and in the process, we find that resonant meaning comes neither from the text, nor from us, but from somewhere between the two. This may explain why there is often a gap between the self-perception of ‘theorists’ and literary ‘writers’. A theorist is often hoping to ‘convey’ their theories, to communicate them unequivocally. A literary writer says “never mind if this is strictly true; is it interesting?” But if a text is interesting, that is a kind of truth. This is why Phillips suggests psychoanalytic writing be read a literature, regardless of the writer’s intention. Freud the writer will outlast Freud thetheorist, or even psychoanalysis itself. And perhaps Freud knew that.

‘Theory’ is often suspicious of the power of ‘literature’, seeing it as rhetorically sly in its way of not appealing to the intellect only. In doing so it often condemns itself to small and specialized audiences. This is why the idea ofthe ‘public intellectual’ is vanishing. But there were never that many public intellectuals, never that many who had found a way to give literary form to their theories. It is very difficult thing to do. What may be vanishing is the desire to even try.

This year has been incredible for Objektiv Press and our Afterimage series. As we wrap up the year, we’ll be sharing excerpts from our books every Monday leading up to Christmas. This is David Campany’s contribution to our A Criticism Review, Objektiv #25.

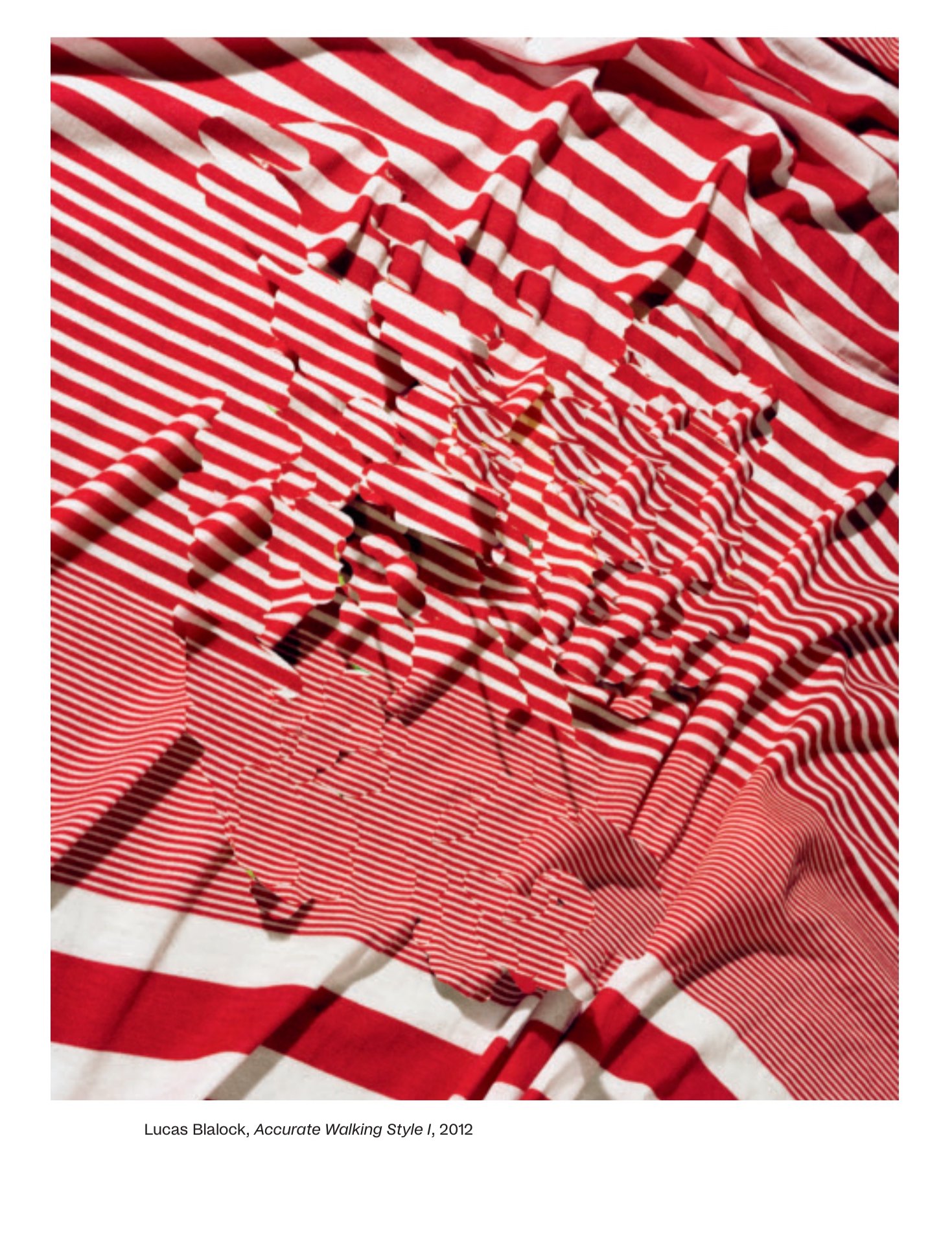

LUCAS BLALOCK

11. In my pictures, I’m always looking for language adequate to my own subjectivity, my own messed-up feelings, and this is something I hope viewers might be able to mirror for themselves. Photography is nothing like a verbal or written language in most respects, but, like language, it is in common use. We all ‘speak’ photography and this makes it a particularly interesting form in which to work. Like language, it changes as our use of it alters, shifting to accommodate new uses, evolving socially, and making space for importations and slang. There is a root system in both, but neither is essentially itself—it becomes by being used.

Afterimage by Lucas Blalock:

11. In my pictures, I’m always looking for language adequate to my own subjectivity, my own messed-up feelings, and this is something I hope viewers might be able to mirror for themselves. Photography is nothing like a verbal or written language in most respects, but, like language, it is in common use. We all ‘speak’ photography and this makes it a particularly interesting form in which to work. Like language, it changes as our use of it alters, shifting to accommodate new uses, evolving socially, and making space for importations and slang. There is a root system in both, but neither is essentially itself—it becomes by being used.

I’m interested in photography the way a poet might be interested in English or Spanish. What can you do with this thing we use every day? How can it be stretched? What can it accommodate? Although my work does have a lot of intervention and gesture in it, I don’t see it as self-expression. It’s more like co-relation or triangulation—trying to drum up potential relationships we both (you and I) share through photography to the world.

So.

How can I get photography to address the real conditions of my experience?

What can I ask photography to do?

From Why Must the Mounted Messenger be Mounted?, by Lucas Blalock, Objektiv #26. Join Blalock, Carmen Winant and Elle Pérez with Objektiv Press during Paris Photo. On Saturday, November 15, at 11h., Delpire & Co. will host a presentation by Winant, followed by a discussion with her, Pérez and Blalock over coffee and croissants.

MARGE PIERCY

I've always been attracted to photography that poses a threat to itself. I probably work the way that I do – using so many found and collected images – because I’m distrustful of how seductive photography can be. But I can't really shake it either: I feel too tender towards the photographic object. I love feeling them, seeing them in relation to each other. I often describe myself as a photographer who doesn't make my own pictures for this reason. T

Afterimage by Carmen Winant:

I've always been attracted to photography that poses a threat to itself. I probably work the way that I do – using so many found and collected images – because I’m distrustful of how seductive photography can be. But I can't really shake it either: I feel too tender towards the photographic object. I love feeling them, seeing them in relation to each other. I often describe myself as a photographer who doesn't make my own pictures for this reason. This is all to say that I’ve been drawn to other people who remodulate our expectations of the image: Leigh Ledare, Jo Spence, Valie Export, Jim Goldberg, Rodrigo Valenzuela, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and so on. And, if I am being honest, I draw more from writers than I do from visual artists. The French poststructuralists and Helene Cixous but also American poets like Marge Piercy, whom I've been re-reading a lot lately. They give me language, but they also – on the best days – help me ideate as I go.

A revised quote by Winant from Carte Blanche, Objektiv #20. Join Carmen Winant, Lucas Blalock and Elle Pérez with Objektiv Press during Paris Photo. On Saturday, November 15, at 11h., Delpire & Co will host a presentation by Winant, followed by a discussion with her, Pérez and Blalock over coffee and croissants.

OBJEKTIV PRESS AT PARIS PHOTO

On the occasion of Paris Photo, Objektiv Press will present this summer’s project Double with Carmen Winant and Carol Newhouse at Les Rencontres d'Arles, featuring a presentation from Winant along with a conversation with her, Elle Pérez and Lucas Blalock over coffee and croissants.

Coffee & Croissants – Delpire & Co

Saturday, 15 November 2025, 11h

We will also hold our tenth pop-up event at Polycopies! This year, we will focus on the books from Winant, Pérez and Blalock,, but other titles will also be available..

Delpire & Co — Saturday, November 15, 11h.

On the occasion of Paris Photo, Objektiv Press will present this summer’s project Double with Carmen Winant and Carol Newhouse at Les Rencontres d'Arles. The event will include a presentation by Winant, followed by a discussion with her, Elle Pérez and Lucas Blalock, over coffee and croissants.

Coffee & Croissants – Delpire & Co

Saturday, 15 November 2025, 11h

Delpire & Co, 13 rue de l’Abbaye, Paris 6e

www.delpireandco.com

Polycopies — Thursday, November 13 & Friday, November 14, 11h–19h.

We’re at Polycopies for our tenth pop-up Thursday and Friday. This year, we will focus on books from Winant, Pérez, and Blalock, but other titles will also be available. Please note: Objektiv Press will be there from 11h to 19h, but the boat will remain open for booklovers until 21h.

The book Double accompanied the exhibition of Carol Newhouse and Carmen Winant at the Rencontres d’Arles. Double invites us to consider how we reinvent ourselves and our histories through shared self-representation and interconnection. Using some works from Newhouse’s archive, their work gives form to intergenerational relationships and feminist legacies, bringing past experimental photographic practices into the present.

the movement of our bodies gathers a decade of celebrated artist Elle Pérez’s reflections around photography. A collage of loose thoughts, letters, press articles and reviews, text messages, pictures, sketches, responses, emails, notes, and lectures, the book explores what Pérez chooses to photograph and what photography means to them. It is a tapestry of personal insights, intimate moments, and candid reflections, all woven through the medium.

Why must the mounted messenger be mounted? by Lucas Blalock, soon to be published in Mandarin, offers an expanded meditation on the artist’s twenty-year involvement with photography. In it, Blalock charts the development of his photographic ideas as they run alongside a tangled web of accidents, influence, romance, anxiety, and work. It is a book about coming of age with a preoccupation alternately in full bloom and on its last legs.

At Polycopies we will also present the new publication from Notes Press, an imprint of Objektiv Press. Notes on Paname by Nina Strand opens during the summer of the 2024 Paris Olympics and moves toward the tenth anniversary of the 2015 attacks. Through brief reflections accompanied by images of bistro terraces, it explores the confusing emotions of love and belonging to a city that isn't one's own.

MANUEL ÁLVAREZ BRAVO

The picture of Jose de Jesus took about a year to make. The image itself holds a reference to Señor de Papantla by Manuel Álvarez Bravo, one of my favorite artists. I had the luck of being able to study his prints when I wasteaching at the Williams College. As with the works of Peter Hujar and Roy DeCarava, so much happens in Bravo’s shadows.

The Man from Papantla (Señor de Papantla) 1934, printed 1977. Manuel Alvarez Bravo

Afterimage by Elle Pérez:

The picture of Jose de Jesus took about a year to make. The image itself holds a reference to Señor de Papantla by Manuel Álvarez Bravo, one of my favorite artists. I had the luck of being able to study his prints when I wasteaching at the Williams College. As with the works of Peter Hujar and Roy DeCarava, so much happens in Bravo’s shadows. They contain so much information that is hard to re-photograph, and therefore it isimpossible to grasp the true sensitivity of his printing until you see the prints in person. The resulting effect of two-dimensional form holding a profound sense of depth and volume is something I think about frequently while photographing, and even more so while printing.

In Jose De Jesus (2018) and in Jose Gabriel (2017), the shadows are crucial. In the latter photograph, the shadows reveal his eyes when you come closer, making him appear to be looking at you. Jose De Jesus offers three modalities of shadow and light, each with its own depth, against a plain wall. Jose De Jesus happened to personally own the Bravo monograph we were using as reference; it was given to him by a friend. So he was familiar with and had a relationship to the specific photograph.

From the movement of our bodies, Objektiv #29. Join Carmen Winant, Elle Pérez, and Lucas Blalock with Objektiv Press during Paris Photo. On Saturday, November 15, at 11h., Delpire & Co. will host a presentation by Winant, followed by a discussion with her, Pérez and Blalock over coffee and croissants.

KETUTA ALEXI-MESKHISHVILI

When we could still afford to have a stable world view, an image could shift our perception of the world. In this sense, it’s the billion collective images that I’ve consumed in the past ten years that have resonated with me the most. Slowly, over time, the power of a single exhibition or image to change one’s perception has been put to question. In a time of relentless and almost involuntary consumption of images, the rise of mass-market digital retouching and live rendering software, can a single image hold power?

When we could still afford to have a stable world view, an image could shift our perception of the world. In this sense, it’s the billion collective images that I’ve consumed in the past ten years that have resonated with me the most. Slowly, over time, the power of a single exhibition or image to change one’s perception has been put to question. In a time of relentless and almost involuntary consumption of images, the rise of mass-market digital retouching and live rendering software, can a single image hold power?

What made me love photography was its boundary problems: how the ambiguous power of decisions such as composition, editing, framing, circulation and presentation of an image tends to determine the meaning more than that which is being depicted. Or, for example, the opaqueness of boundaries between the depicted and depicter that are easily blurred by the dynamics of power. These tendencies allow photography a vast, mysterious area for an artist to investigate and play in. What has surprised me most lately, in my inquiry into this phenomenon, is how closely the experience of motherhood has paralleled it and in turn, has fed my images post-partum.

My exhibition at Galerie Frank Elbaz in Paris, that was titled mother, feelings, cognac, was an attempt to communicate a sense of lost boundaries, between bodies, images, definitions: a certain amnesia, personal and general, if you will. Recently, I sense myself moving away from that as well, but whatever is brewing is very new and I can't yet verbalize it.

Artists have been foreshadowing our ‘post truth’ moment for a long time. I think whether directly or indirectly, all work is affected by the broader realities of its time. Generally, I don’t set out to comment on things through my work. Following the last US presidential election, however, I was invited to participate in a group show called Produktion: Made in Germany Drei, at the Sprengel Museum in Hannover. For this exhibition I worked on a concise project, titled MID, where I photographed – off the computer screen – found images of window locks produced in Germany. I also added a crumpled ribbon of a different colour to each image, in order to keep things open to interpretation. But the images still turned out to be too resolved for me. After that experience, I turned in again, hoping that the personal, with its call to empathy, can also be political.

What comes after the pictorial turn? Instagram has eaten Facebook, fashion is having pop culture for breakfast, emojis are feasting on the written word, and most of human communication is taking place on a screen. Maybe the pictorial turn is the last turn we make before the end.

From the final issue of Objektiv in 2020, marking its tenth anniversary. We gave twenty artists carte blanche to create portfolios or collage-like mind maps exploring the photography that inspires their practices. Each contribution was accompanied by a short statement.

Though not part of our Afterimage series, these contributions touch on themes of memory and perception. The artists were prompted with a set of inspirational questions, including one posed to W.J.T. Mitchell: What comes after the pictorial turn? He responded:

‘I think the study of the whole sensorium – the senses themselves, beyond vision, or as connected to vision – is one thing that follows logically after an emphasis on the visual. I never thought of images as silent; even silent movies were never silent: they had music and text.’

LEBOHANG KGANYE

Santu Mofokeng’s photographs from the series Chasing Shadows and Black Photo Album/ Look At Me & Carrie Mae Weems’ images from Kitchen Table Series and Family Pictures are still on my mind. The influences and events that have changed the atmospheric pressure of my working space are oral histories, self-recollection and the recollection of others, autobiographical narratives, psychoanalytic theory and therapeutic practice dealing with transgenerational trauma.

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Playing Cards/Malcolm X) from the Kitchen Table II series, 1990 © Carrie Mae Weems, courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery.

Afterimages by Lebohang Kganye:

Santu Mofokeng’s photographs from the series Chasing Shadows and Black Photo Album/ Look At Me & Carrie Mae Weems’ images from Kitchen Table Series and Family Pictures are still on my mind. The influences and events that have changed the atmospheric pressure of my working space are oral histories, self-recollection and the recollection of others, autobiographical narratives, psychoanalytic theory and therapeutic practice dealing with transgenerational trauma, and the social and political climate of South Africa in the present, as well as its history, especially language and oral history. Naming and oral history is directly linked to the prohibition against black people learning to read and write in the context of apartheid. This attests to the power of literacy – voting was connected to the ability to read and write.

Santu Mofokeng, Eyes-wide-shut, Motouleng Cave, Clarens – Free State, 2004. Courtesy: the artist and Kunsthal Extra City, Antwerp

When asked about what comes after the pictorial turn, I’ve been thinking about ghosts – multitudinous manifestations and co-existences in a timespace between past and present – and Roland Barthes’s use of death as a metaphor for photography: the ‘presence of absent figures’ and an ‘always-already absent present’, which is ‘neither present, nor absent’. So for me, photography is a ghost, an existence in transition, hovering in a duality of time. By considering time as a construct, one can consider the ghost as a single being or as multiple possible presences, whether it is a spectre from the past, appearing in the present, or a spectre from the present, seeking refuge in the past.

From the final issue of Objektiv in 2020, marking its tenth anniversary. We gave twenty artists carte blanche to create portfolios or collage-like mind maps exploring the photography that inspires their practices. Each contribution was accompanied by a short statement.

Though not part of our Afterimage series, these contributions touch on themes of memory and perception. The artists were prompted with a set of inspirational questions, including one posed to W.J.T. Mitchell: What comes after the pictorial turn? He responded:

‘I think the study of the whole sensorium – the senses themselves, beyond vision, or as connected to vision – is one thing that follows logically after an emphasis on the visual. I never thought of images as silent; even silent movies were never silent: they had music and text.’

EM ROONEY

As a student I was obsessed with Steiglitz’s photographs of Georgia O'Keeffe, how we could watch her age (becoming more handsome with every year). We saw what Steiglitz saw (although O’Keefe lived much longer after he died). What a privilege the photographer grants the viewer, a stranger to the world of her intimacy.

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1919/21, Palladium print, Alfred Stieglitz Collection.

Afterimages by Em Rooney:

The way that I’ve often thought about photographs as private, personal, and small I think might have its roots in the way photographs were often stored at my house when I was growing up. They weren’t typically on display. They were in hidden in boxes in the attic, or shoved in the pages of books – old family photos, or pictures of my mother in High School might drop out of the OED or the Joy of Sex when you pulled them off the shelf. So that relationship between the page, and image (and its one that Sontag, Barthes, Berger, Davey, and many others have often spoken about) was there for me when I was a child, and has reoccurred formally, on and off, throughout the past ten years.

This time has been stuffed to the gills with non-stop reading about, teaching about and seeing shows; talking about work (with my love, artist and collaborator Chris Domenick) first thing in the morning, last before bed at night; getting into serious fights with friends about work they like/don’t like and why; writing about work I love and curating shows, and pouring myself into it. This question, of what has resonated with me, would be incomplete unless it were to include the work of all my friends and everything I learned from Chris and his practice, and every show I’ve seen and then verbally dissected (not to mention the work of so many gifted students I’ve taught since 2010) – the number is probably in the thousands.

Catherine Opie’s show at Lehmann Maupin, comes to mind. It featured the artist Pig Pen as protagonist in a fictional, doomsday narrative laid out in a series of photographs and a video. Pig Pen (aka Stosh Fila) is a person I love looking at who Opie has been photographing for years. The magic of the photograph can be very simple, just like that; I like looking at you. And this is a watered down version of punctum I guess. It's captivating to think about who or what a photographer photographs over time. What subject does she return to? As a student I was obsessed with Steiglitz’s photographs of Georgia O'Keeffe, how we could watch her age (becoming more handsome with every year). We saw what Steiglitz saw (although O’Keefe lived much longer after he died). What a privilege the photographer grants the viewer, a stranger to the world of her intimacy. Opie’s show felt particularly impactful, in this way, as I realized her subject, had become someone I’d grown up with as well.

I think the pictorial turn might be the last turn, especially if we think of it in relationship to Foucault’s ideas about surveillance. I’ve seen corporate tools and machines that render quality/detail/data more quickly and easily, tools that are historically and presently, used for military and capital gain; drones and advanced data processing systems, used well by responsible artists. But, I worry that the merging of scientific/corporate invention and genuine creativity will continue to alienate us from our physical world, biochemical feelings, observations and instincts and this will hasten the destruction of the planet.

From the final issue of Objektiv in 2020, marking its tenth anniversary. We gave twenty artists carte blanche to create portfolios or collage-like mind maps exploring the photography that inspires their practices. Each contribution was accompanied by a short statement.

Though not part of our Afterimage series, these contributions touch on themes of memory and perception. The artists were prompted with a set of inspirational questions, including one posed to W.J.T. Mitchell: What comes after the pictorial turn? He responded:

‘I think the study of the whole sensorium – the senses themselves, beyond vision, or as connected to vision – is one thing that follows logically after an emphasis on the visual. I never thought of images as silent; even silent movies were never silent: they had music and text.’

LUTZ BACHER

Shadows and forms seem to reach out of the frame and pass right through the installation space. A hand approaches or withdraws from a chest blemished by marks. The fragility of this skin that has just been touched or is about to be touched contrasts with the image itself, which manages to convey the opposite of fragility. The black and white photograph comes from another time and yet is so necessary in our time.

Untitled (1975), Lutz Bacher. Image courtesy of the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin, and, Greene Naftali Gallery, New York.

Afterimage by Susanne M. Winterling:

Shadows and forms seem to reach out of the frame and pass right through the installation space. A hand approaches or withdraws from a chest blemished by marks. The fragility of this skin that has just been touched or is about to be touched contrasts with the image itself, which manages to convey the opposite of fragility. The black and white photograph comes from another time and yet is so necessary in our time.

The photo was shown in the exhibition Black Beauty, which included an installation in which tons of black coal slag filled the entire gallery floor, and the site-specific work Black Magic, made from vibrating black astroturf cladding the walls. The glimmering sand-like coal seemed to point to the photograph, which was placed next to the viewer’s path of the architecture. The resulting dynamic was both of lightness and heaviness, as the exhausting playfulness and desolation of the sand found a correlation in the awkward intimacy of the photograph.

This ambivalence is perhaps why this photo in particular has remained with me – its violent affirmation of a skin too thin. Like a spark, the image illuminates a certain and defined materialism within the virtual flow of information and image technology. Without concrete stability, it nevertheless affirms a dynamic and thus a reality, but one that will always remain vague, even though so visceral.

This afterimage is from Objektiv #8, 2013. Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

ELINE MUGAAS

I’veI’ve been thinking about something that Eline Mugaas once told me: a film still that has stayed with her for a long time. The scene is from one of Constantin Brancusi’s films shot in his Paris studio. A woman is dancing on a low plinth, her body twisting as she raises her arm above her head. The movement reminded Mugaas of other images throughout art history, from antique caryatids – columns shaped like women's bodies whose function was to hold up temple roofs – to the Greek urns from the geometric period, stylised as women raising their arms above their heads and pulling their hair in grief.

Eline Mugaas, Pillow I-IV, 2019.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

I’ve been thinking about something that Eline Mugaas once told me: a film still that has stayed with her for a long time. The scene is from one of Constantin Brancusi’s films shot in his Paris studio. A woman is dancing on a low plinth, her body twisting as she raises her arm above her head. The movement reminded Mugaas of other images throughout art history, from antique caryatids – columns shaped like women's bodies whose function was to hold up temple roofs – to the Greek urns from the geometric period, stylised as women raising their arms above their heads and pulling their hair in grief. She thought of the writhing female bodies in the paintings of both Matisse and Modogliani, all of this reminding her of the movement made when swinging an object up on one’s head or lifting a child on one’s arm.

When Brancusi installed his Endless Columns, he filmed his trip to Romania. Mugaas watched the film repeatedly and found, in a one-and-a-half-second frame, a woman at a market carrying a tin on her head with the same form she had on her mind. She saw it as a serendipitous moment, where everything comes together, belongs to each other or is created from each other. This idea of lifting, supporting and carrying is on display in Mugaas’ work Pillow I-IV, which contains images of seated sculptures taken from the Ludovisi throne at the Roman National Museum.

This afterimage is inspired by a text I wrote about Mugaas's work for Camera Austria. Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

INGRID EGGEN

Still thinking about Ingrid Eggen's pedknots. They look so uncomfortable that it actually hurts to watch. It seems as though toes have been amputated. This makes me think about how we continue to survive in our bodies. Eggen has consistently worked with the human form throughout her artistic career – previously using symbols and signs tied to communication, where she explored how physical expression can be distorted to create something new, based on the body’s unconscious ways of collecting and storing information.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

Still thinking about Ingrid Eggen's pedknots. They look so uncomfortable that it actually hurts to watch. It seems as though toes have been amputated. This makes me think about how we continue to survive in our bodies. Eggen has consistently worked with the human form throughout her artistic career – previously using symbols and signs tied to communication, where she explored how physical expression can be distorted to create something new, based on the body’s unconscious ways of collecting and storing information.

As the exhibition text describes, the works are part of an ongoing exploration of how organisms and ecosystems have developed clever, innovative solutions to problems through evolution and adaptation, and how the human body might be transformed in response to future changes – a potential vocabulary for the body's affective intelligence.

I pick up the accompanying text, a short fictional piece by Ruby Paloma, where she paraphrases Samiya Bashir's quote: ‘How will we survive this having a body? Trying to be intelligent life,’ with: ‘Perhaps the body is the most intelligent part of us.’ And maybe this is why I’m so fascinated by Eggen's insistence on photographing the body. For how are we, as the accompanying text asks, supposed to survive being a body – in the face of the world's development? These works feel important, like the beginning of something larger in an attempt to evoke a new form of corporeality – shaped by the lived experiences of the body.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

SOPHIE RISTELHUEBER

My bag is heavy with books about other artists as I walk through the vast halls of the museum. I’m so impatient to find the Becker that I barely register Bourgeois’ Maman, which usually makes my breath catch. I only stop when I reach the large-scale black and white piece by Sophie Ristelhueber—scarred skin from her Every One series, inspired by her visit to war-torn Yugoslavia. The photographs were taken in a Paris hospital: fourteen close-up images of post-surgical scars serving as symbolic stand-ins for the wounds of conflict.

Sophie Ristelhueber, Every One (#3), 1994.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

He has a plaster under his left eye—something has been removed. As he sits down, he tells me not to worry. It was only a birthmark his doctor wanted to take off, nothing important.

‘There will be more,’ I say to him. ‘Each time we meet, another small part of our bodies will be taken away.’ One by one, we’ll be stripped down. There will be less and less left of us. ‘And the worst thing,’ I say,’is that we’ll find this completely normal.’ 'It's just age,' we'll tell each other, nodding knowingly.

While Jean goes to see Louis Vuitton’s Homme show at the Palais de Tokyo—an event I’m in no way invited to—I visit the Musée d’Art Moderne. Some years ago, they hosted an exhibition of Paula Modersohn-Becker’s work, including the self-portrait that appears on the cover of the book I’m currently reading: she is pregnant, holding an extra body inside her.

The curator wrote that in her ‘numerous self-portraits, Modersohn-Becker asserts her identity as a woman, portraying herself intimately and without complacency, in an ongoing quest for her inner being.’ But I can’t find that self-portrait anywhere. I know the museum acquired another piece from that exhibition—a portrait of her sister, Herma. It’s a close-up. She wears marigolds on her hat. I want to see it.

My bag is heavy with books about other artists as I walk through the vast halls of the museum. I’m so impatient to find the Becker that I barely register Bourgeois’ Maman, which usually makes my breath catch. I only stop when I reach the large-scale black and white piece by Sophie Ristelhueber—scarred skin from her Every One series, inspired by her visit to war-torn Yugoslavia. The photographs were taken in a Paris hospital: close-up images of post-surgical scars serving as symbolic stand-ins for the wounds of conflict.

I think about Jean and me laughing about losing body parts. And now, standing in front of someone who has. I know that Paula’s last word was: ‘Schade.’ Dying eighteen days after giving birth. Her sister Herma is somewhere in this building, wearing marigolds on her hat. One of the few things Paula left behind.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

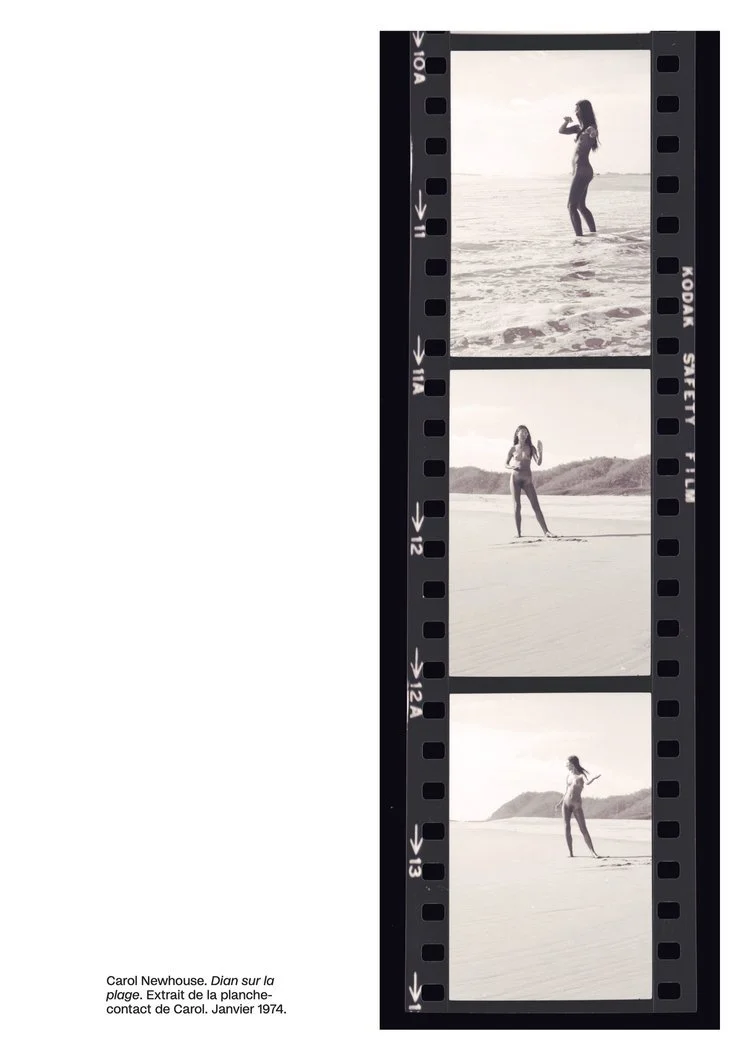

DOUBLE Carol Newhouse & Carmen Winant

Double opens with a series of photographs of a woman practising Tai Chi on a beach, apparently alone, moving in and out of the waves. She seems lost in her own movements. The year is 1974, and the woman, along with her two friends, is weeks away from discovering the land where they will build a new community. They have left everything—their homes and families—to find a place where they can live outside society. This short photo-novel of the woman on the beach serves as a symbol of that dream.

A page from the book Double Carol Newhouse & Carmen Winant.

Double opens with a series of photographs of a woman practising Tai Chi on a beach, apparently alone, moving in and out of the waves. She seems lost in her own movements. The year is 1974, and the woman, along with her two friends, is weeks away from discovering the land where they will build a new community. They have left everything—their homes and families—to find a place where they can live outside society. This short photo-novel of the woman on the beach serves as a symbol of that dream.

And let this dream begin with Carol, who captured the series on the beach. In the 1976 book Country Lesbians, about the community they built, we learn that she and the woman on the beach, Dian Wagner, met in college and later lived with Carol’s then lover, Billie Miracle, in a collective in Nova Scotia. Wagner dreamed of returning to the States to buy land, envisioning a future where they could build a more sustainable and independent life. Later, Carol recalls that they didn’t feel as if they would need to give up very much. Even if they didn’t know where and what the land they eventually found would be, they were just filled with passion and a confidence that they would find something better. They knew they had to leave a system they felt was harmful to them.

(…)

This dream of a new future was something that Carmen also sought. For her 2018 project My Birth, she extensively researched the international lesbian-separatist communities and became fascinated by these images that capture a radical movement toward lesbian self-determination. As she puts it, these photographs, created by and for women, reflect a world rooted in mutual recognition: women behind the camera, photographing one another and building lives outside the structures of patriarchy. In this context, photography becomes both a survival strategy and a shared language—an archive of intimacy, pleasure, labour and resistance.

An excerpt from Double. Order your copy now at our online bookstore.