WALKER EVANS

Afterimage by Bjarne Bare:

While the documentary image is haunted by the decisive moment, the studium calls for a more refined and contemplating dialogue. An unfinished message that seeks context in order to be read. Walker Evans seems to hold a special photographic gaze. Jean-Paul Sartre describes a person entering a bar and gazing through the locale, but as soon as the eye catches another eye, the gaze disappears, the magic is broken. ‘I no longer see the eye that looks at me and, if I see the eye, the gaze disappears.’ In such, I find Evans photographic work function as a pensive gaze more than a straight photographic document. Or as Lacan puts it: ‘In our relation to things, in so far as this relation is constituted by the way of vision, and ordered in the figures of representation, something slips, passes, is transmitted, from stage to stage, and is always to some degree eluded in it — that is what we call the gaze.’

When documenting Floyd Burroughs’ family and home for Let us Now Praise Famous Men in 1936, Evans’ isolated focus on the objects caught my eye. A chair flanked by a white sheet and a broom. An empty bed. A pair of workers shoes. Utensils. Along with the portraits he made, the closeups of details describe the life and situation more than the actual faces. As if, in the portraits, the gaze is broken. Along with the use of his gaze, Evans also distances himself from the traditional mode of documentary practice. There is little or no action in his photographs, yet we do experience the situation, through the focus on details. The images are silent, and their immanent communication is key. They are studies. In this, a photographic language develops, one which is more formal, perhaps, but also stays away from the usual photographic realism, where motion, portraiture and action is the modus operandi. When focusing on objects, such as the boots in the negative space, the empty bed, or the chair flanked by the broom and sheet, Evans lets the image breathe, look at you, rather than having the person in the image speaking. It is as if Evans trusts the image, the photography and its silence.

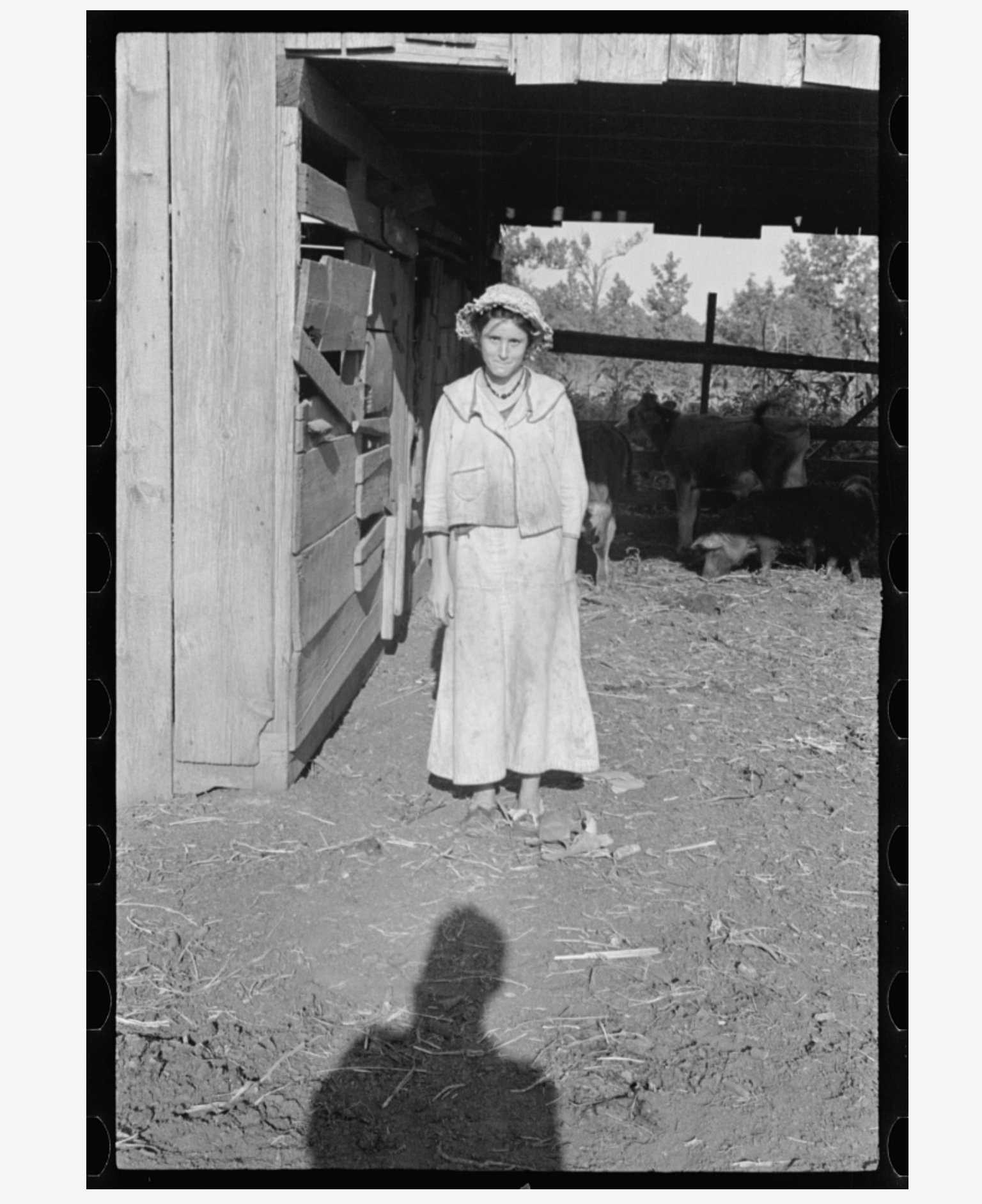

Walker Evans, Dora Mae Tengle, sharecropper's daughter, Hale County, Alabama, 1936.

While writing this, I remembered seeing an image of Evans included in an exhibition at Standard (Oslo) in 2013. The exhibition included mainly contemporary work, and I was puzzled by the inclusion of the Evans piece. I am now, perhaps, understanding this better, as if it was an ode to Evans’ mind and eye. It is hard for me to define the postmodern project in photography, although it carries importance. I find the time we are in, photographically, somewhere in between modernity and postmodernity – and thus work created today should be informed by both. If a documentary approach still can be relevant, or at least exist, the straight photographic document is no longer enough – as if its naiveté is broken. Narration is no longer key. The images look back at us, and we are better informed in reading them now than ever before. In looking at Evans’ work dating nearly 80 years back, I have found relevant use and understanding of the photographic image. In Dora Mae Tengle, sharecropper's daughter, Evans’ Friedlander-esque approach reveals something to me. Not only does he include himself in the image (there is a similar approach among his images of flood victims), but he also destructs the gaze, creating a similar effect as to the more recent Gazing Balls by Jeff Koons. The neutrality of the image is broken, the image looks back, and the photographer is present. This – what seems to be a simple snapshot – holds so many layers of photographic understanding. Along the other work by Evans’ it makes him a highly relevant photographer in the quest of understanding the potential for the straight image in a contemporary discourse.