DOUGLAS GORDON

It could be the image of the watermelon that lingers in my mind as I sit at Zürich Flughafen, waiting for a flight from a non-EU country back to my own. The reopening of Fotomuseum Winterthur has been reassuring—it’s a place where lens-based art is taken seriously. And this series on how we relate to emojis in our digital world feels important.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

Douglas Gordin. Taken by the author seeing the exhibition WALL WORKS & SCULPTURES at Galerie Eva Presenhuber in Zürich, 16th of May, 2025.

It could be the image of the watermelon that lingers in my mind as I sit at Zürich Flughafen, waiting for a flight from a non-EU country back to my own. The reopening of Fotomuseum Winterthur has been reassuring—it’s a place where lens-based art is taken seriously. And this series on how we relate to emojis in our digital world feels important, especially that symbol this weekend, being in the host country of the music competition, where one nation should probably not have been allowed to participate.

There’s so much to take in after the exhibition—and from my afternoon wandering Zürich, just twenty minutes away by train. The city holds it, too, in small ways: graffiti on the walls that reads Free Gaza. It stays with me, especially when I see a work made of scaffold dust sheets and other materials, said to suggest that buildings—and maybe societies, too—are always in progress, never truly complete. I think of it again as I pass a man sitting in a window, sipping wine and watching the people below. It’s a clever, much cheaper way to people-watch, but I wonder if he’s sitting up there alone because he’s afraid to join the rest of the world. Does he need help?

When I can’t see more art—everything is closed—I have a glass of wine at Kronenhalle, a tip from two different friends. I sit next to some artists and gallerists speaking in excited tones about an opening yesterday at a place that, sadly, wasn’t on my itinerary. They’re also talking about next year’s Venice Biennale and what will happen now that its curator has passed—something I’ve also thought about. Where do all her visions for next year’s edition go?

There’s something familiar about the woman sitting in the corner of their group. I want to look her up, but instead, I ask if they could watch my things while I look at the art in the restaurant. When I return, she laughs and says she never took her eyes off my stuff. I want to move closer to their conversation.

Later, at the airport, I look up images of one of the most famous Swiss artists I know—and it is her. I got her. I got all the art. But what is it I’m really looking for, walking and taking trams all over these two cities to see as much as I can in the short time I’m here? What does it help, anyone suffering?

Waiting for my plane, I thought I was sitting down to write about the fruit emoji. But instead, I think of a text work I saw on one of the gallery walls: Where does it hurt? I mumble to myself: Everywhere.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

PATRICK NAGATANI

Although this body of work was made over two decades ago during the high phase of postmodernism, its concerns around the way that truth is constructed resonated deeply. Its critical engagement that is, with the photographic image as a composite of interwoven narratives and suspensions of disbelief, felt timely and urgent against the backdrop of a politics increasingly stranger than fiction.

Patrick Nagatani, Spectacular Proof, 1994.

Afterimage by Matthew Rana:

Although this body of work was made over two decades ago during the high phase of postmodernism, its concerns around the way that truth is constructed resonated deeply. Its critical engagement that is, with the photographic image as a composite of interwoven narratives and suspensions of disbelief, felt timely and urgent against the backdrop of a politics increasingly stranger than fiction.

Patrick Nagatani, Amazing Image, 1994.

Like much of Patrick’s work, Novellas evokes the spectacular, media-saturated landscape of late capitalism. But unlike his better-known directorial projects, such as the collaborations between 1983 and 1989 with painter Andrée Tracey, which stage fictional scenarios in elaborate, often ambiguous tableaus, the Novellas are more collage-like in their approach. Using a variety of mediums and techniques to create densely layered compositions, they incorporate a broad range of imagery including advertisements, film stills, religious etchings and archival photographs.

As the title suggests, each image reads like fiction — a page or passage in a short story. Yet whereas Patrick’s other projects from the same period, such as Nuclear Enchantment (1988-93), Japanese-American Concentration Camps (1993-95), or Ryoichi Excavations (1985-2000), tend to cohere around a single theme, history or character, Novellas is more fragmented, and plays out on a distinctly personal register, exploring themes such as sexuality, spirituality, race and gender; symbolic anchor points of the self.

I was saddened to learn of Patrick’s passing at the age of 72, following a decade-long battle with colon cancer. As way to remember his artistic legacy and vision, I want to offer a selection of his Novellas here: a sequence of five large-format Polaroids from 1994 in which covers from the now-defunct publication Weekly World News — a supermarket tabloid known for outlandishly manipulated photographs claiming to depict supernatural and paranormal phenomena — feature. Also appearing in each image, a $5 novelty photograph in which Patrick’s head is digitally superimposed atop a figure shaking hands with then-president Bill Clinton. The dissonance that these images create still feels oddly synchronous with, for instance, the curious mix of faith and paranoia that seems to structure the American imagination at present. They are Amazing, Divine, Miraculous, Spectacular, and Terrifying.

This text has been edited, was originally published on our web journal in 2018. Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

TOM SANDBERG

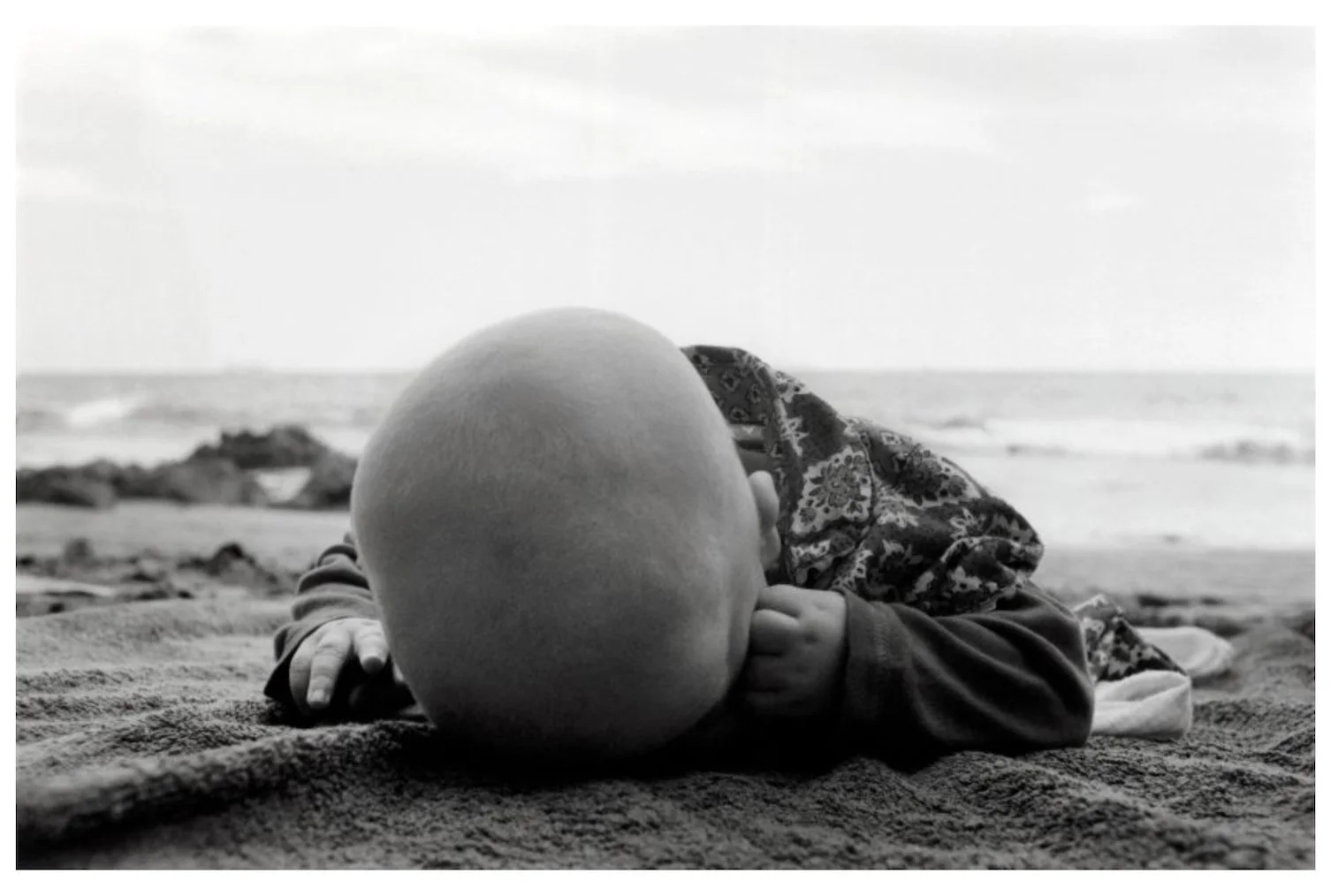

I find myself drawn to images that carry an ambiguity—a kind of visual dissonance. A story only half-told. Something has happened, and the image holds that space open. I think of Tom Sandberg’s photograph of a child with their head buried in the sand. That quiet tension, that sense of something just beyond reach.

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2004.

Afterimage by Linnea Syversen:

I find myself drawn to images that carry an ambiguity—a kind of visual dissonance. A story only half-told. Something has happened, and the image holds that space open. I think of Tom Sandberg’s photograph of a child with their head buried in the sand. That quiet tension, that sense of something just beyond reach.

There is a photograph I keep returning to—an image by Hans Olav Forsang from his Human Tonic series. A white horse. A picture that stays with me. It is visually beautiful, yet, at the same time, unsettling. The first time I saw it, I stood still for a long time. My eyes were drawn to the horse’s eye. It looked as if it had been sewn shut or was simply missing, leaving me with many questions. Later, I learned that the horse was blind after an accident, but at the time, I didn’t know. I just stood there, thinking.

Hans Olav Forsang, from his Human Tonic series, 2017.

I have often reflected on how we humans make decisions for animals when they are injured or ill. We are the ones in power who define what a worthy life is. We speak on behalf of their silence. Perhaps this horse was perfectly fine, but in the photograph, its ears are pinned back, its nostrils flared—signs that can indicate distress. Maybe it was frightened, or maybe it was just a fleeting moment of tension. Or maybe that moment of tension was simply that—a moment. We don’t know. And that’s precisely why the image stays with me. It doesn’t give answers. It asks.

Photographs claim to capture truth, but what they offer is always just a fragment—a frozen frame that conceals as much as it reveals. They can show us reality, but not its entirety. That thought lingers with me: how quick we are to interpret what we see through the lens of our own emotions and assumptions.

This makes me think about how we perceive the unfamiliar—a disability, an injury, something outside our usual experience. We want to understand, to categorize. But there are things that resist such clarity. We project our own emotions onto what we see and what we know, but we don’t always see the full picture. Life is given, and while some can shape it, others must simply take it as it comes and as it has been given. To me, the photograph becomes more than an image of a horse. It becomes a quiet meditation on power and vulnerability. here is something about black and white. I love color—it’s a cliché to say—but perhaps black and white strips away some of the noise. It forces us to confront what is, without distraction.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

TREVOR PAGLEN

There is an image of Simone de Beauvoir on my mind. It’s a composite photograph, created by blending images identified as her by facial recognition programs. The result is an AI-generated portrait: a machine’s interpretation of identity. It’s surreal, yet strangely vivid—a young version of de Beauvoir—but I remind myself that it is a photograph never actually taken, she never posed for this and yet it now exists in the world. Its subtitle, Even the Dead Are Not Safe, feels truer than ever.

Trevor Paglen, De Beauvoir (Even the Dead Are Not Safe) Eigenface, 2017. © TREVOR PAGLEN.COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND METRO PICTURES, NEW YORK.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There is an image of Simone de Beauvoir on my mind. It’s a composite photograph, created by blending images identified as her by facial recognition programs. The result is an AI-generated portrait: a machine’s interpretation of identity. It’s surreal, yet strangely vivid—a young version of de Beauvoir—but I remind myself that it is a photograph never actually taken, she never posed for this and yet it now exists in the world. Its subtitle, Even the Dead Are Not Safe, feels truer than ever.

I think about this non-image as you walk through a darkened room filled with sculpted heads—disembodied forms that evoke the sensation of the dead still living among us. Like Whitney Houston on Instagram, where I see endless reels of her tragically destroying herself with drugs. Even Princess Diana is alive there, smiling conspicuously. It feels as though the dead will return to haunt us, and some should, for we didn’t do enough to protect them.

I passed Beauvoir’s grave the other day, on my way to see the house of Agnès Varda, who’s also gone. I wonder what they might make of us now. Of where we are. Of what we do. I wish I could turn back time so that the women who call themselves feminists hadn't made that ridiculous trip into space—crammed into a tiny craft, too aware of every camera. Watching them, it was as if they didn’t exist. That they weren’t really there, only creating images of themselves rather than actually living, reducing themselves to constructed, non-existent selfies.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

HELMUT NEWTON

From Objektiv’s very first issue in 2010, we’ve asked a wide range of people to describe the image they can’t get out of their minds. Afterimages is an ekphrastic series about that one image that lingers behind your eyes—the one that won’t let go. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can’t shake. This column has been part of Objektiv since the beginning, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series asks: which visuals linger and take root in today’s endless stream? Much like a song that plays on repeat in your head, these images stick. Whether it’s a billboard glimpse, a newspaper portrait, a family photo, or an Instagram reel—we’re drawn to those fleeting moments that stay with us.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There’s a still in the film about Yves Saint Laurent—he’s in his studio at 5 Avenue Marceau, sketching a dress. I can’t remember whether I saw it in the nine-minute film about his life, shown in a small projection room at the Musée Yves Saint Laurent, or in the one projected on the wall as I stood in his studio, completely awestruck to be in the very room where he created those empowering vêtements. He draws with such ease and precision, and it’s clear how deeply he believed in the power of clothes to transform a woman.

I'm at the museum with my friend, whom I’ve known since high school. We’d just come from the Palais Galliera, where she said she could spend hours, showing me the hand-sewn garments and explaining how long they took to make, pointing out the sewing needles still resting on the late designer’s desk. I’ve never been especially interested in the history of clothing—but that’s about to change. We don’t know it yet, standing here at YSL, but by the end of the day, luck will take us to Atelier 1900 – Cygne Rose, where we’ll meet la propriétaire, who we later learn is also involved with the Musée de la Femme. There, visitors can explore the lives of 18th- and 19th-century women through antique dresses, costumes, textiles, and accessories.

Right now, in this room where Yves actually worked, I can’t help but think of Helmut Newton’s photograph of a woman standing in a Marais street, wearing Le Smoking—shot for a Vogue series. That image became iconic, inspiring a revolution in the social codes of its time. Newton and, certainly, the designer both imagined a detached, powerful, liberated woman—wearing a tuxedo once reserved solely for men.

The fact that one day in Paris—a fashion metropolis—showed me how the lineage of women’s clothing is interwoven with the history of liberation has transformed me.

On the Afterimages:

Objektiv Press celebrates 15 years this April. Founded in 2009 as a gallery in journal format, Objektiv began as a biannual publication dedicated to lens-based art. After a decade of exploring this format, we transitioned to a more book-like publication—inviting a single writer to fill the pages with their real and raw opinions on various trends within the medium.

Since 2020, we’ve invited a range of voices—photographers, critics, curators—to reflect on their relationship with photography through longer essays. Our aim is to deepen our content and continue exploring the development and role of film and photography, both within the art world and in society at large.

From Objektiv’s very first issue in 2010, we’ve asked a wide range of people to describe the image they can’t get out of their minds. Afterimages is an ekphrastic series about that one image that lingers behind your eyes—the one that won’t let go. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can’t shake. This column has been part of Objektiv since the beginning, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series asks: which visuals linger and take root in today’s endless stream? Much like a song that plays on repeat in your head, these images stick. Whether it’s a billboard glimpse, a newspaper portrait, a family photo, or an Instagram reel—we’re drawn to those fleeting moments that stay with us.

We encounter so much each day—what does it do to us? According to Phototutorial, by 2025, humanity will take approximately 2.1 trillion photos. In the Western world, we may snap 20 photos a day, while the average person, immersed in a media-saturated environment, is likely to see between 4,000 and 10,000 images daily.

Several contributions offer fresh perspectives on these visual imprints, inviting valuable reflections on what photography can be, and how we interpret images today. Art criticism is subtly woven through many of the texts. Most people responding to our question about afterimages have found visuals that echo their thoughts or emotions. Many texts explore seeing oneself through an image—literally and metaphorically. This includes self-portraits, mirror images, or how an image can stir something deeply personal or existential. Old photographs, childhood memories, grandparents, and lost moments are recurring themes. The image becomes a vessel of time—or frozen time.

One afterimage emerged when an art historian fed a sentence from The Songs of Maldoror by Comte de Lautréamont into an image generator: “...like the random collision of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissection table!” The output included an umbrella and a sewing machine, but also an unexpected object: a medical chair, draped in what looked like a surgeon’s gown, with a metal bowl on top. It had taken the thought a step further.

Many contributors share reflections, ekphrases, and use images as gateways into something personal:

A gallery owner describes a photo she would love to own—of a drink on a plane taking her away from daily life.

An artist reflects on the unsettling image of Pogo the Clown, and how a clown can appear so evil.

An author discusses a photo of a sick Helmut Newton, which we couldn’t publish. Instead, we photographed the book where the image appeared and referenced it.

The Danish Minister of Culture recalls an image of a public servant buried under a mountain of documents.

An author reflects on a photo from Utøya, July 22nd. We did not publish the image at his request—the description alone was haunting enough: lifeless bodies.

An artist speaks of the sisters from Gaza, captured in a video still, the eldest carrying the youngest.

A photo editor remembers an image of a son setting out to sea for the first time since his father drowned—an image that continues to haunt him.

I believe this series has lasted fifteen years because we need space to talk about everything we’ve seen—and to process our impressions. It endures, too, because it is democratic. All images are welcome.

Many texts dwell on what is no longer there. Loneliness and longing often emerge—sometimes more than you might initially notice. These images act as mirrors: we don’t just see their subjects, but also our own grief, dreams, and anxieties.

GRACIELA ITURBIDE

Later, I wrote a thesis using Roland Barthes’ idea of the punctum in an image, exploring how this was my first encounter with such a punctum. It became an image that is very dear to me; I’m still captivated by it many years later, and it continues to evoke strong emotions for me.

Graciela Iturbide, Carnival, Tlaxcala, Mexico, 1974.

Afterimage by Pauline Koffi Vandet:

I saw this many years ago, and it still gives me goosebumps. After high school, I took a year-long sabbatical and was in London, where my interest in art—especially photography and new media—began. I have this image to thank for that. I was at Tate and came across a retrospective exhibition of the artist Graciela Iturbide. As I entered one of the rooms filled with many photographs, this one stood out. I can’t quite say what it was, but it was visually captivating in a way that immediately caught my attention. I couldn’t figure out exactly what it was that captured me.

Later, I wrote a thesis using Roland Barthes’ idea of the punctum in an image, exploring how this was my first encounter with such a punctum. It became an image that is very dear to me; I’m still captivated by it many years later, and it continues to evoke strong emotions for me. I think this is because it’s so uncanny: the mask is human-like, yet not entirely. It appears to be a person in a carnival suit. To me, it is a genderless or perhaps genderfluid being, and from my perspective it could be either living or non-living. There’s something deeply alluring about it. The plain background, which doesn’t compete with the figure, helps focus attention on the masked being.

This photograph is an acknowledgment of the deeply personal and non-universal nature of Barthes’ punctum to me. While many walked past it, it absorbed me and has never let me go.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

PETER HUJAR

There is a seagull in Peter Hujar's exhibition Eyes Open in the Dark at Raven Row. It's Sunday noon, 23 March 2025—spring, with warm, damp air, soft and almost raining. Last night, my friends and I went to see The Seagull (Chekhov) at the Barbican in London, with Cate Blanchett in the lead role. Actually, there are no lead roles, it is directed by Thomas Ostermeier.

Peter Hujar, Dead Gull, 1985 © 2025 the Peter Hujar Archive / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY, DACS London, Pace Gallery, NY, Fraenkel Gallery, SF, Maureen Paley, London, and Mai 36 Galerie, Zurich.

Afterimage by Pia Eikaas:

There is a seagull in Peter Hujar's exhibition Eyes Open in the Dark at Raven Row. It's Sunday noon, 23 March 2025—spring, with warm, damp air, soft and almost raining. Last night, my friends and I went to see The Seagull (Chekhov) at the Barbican in London, with Cate Blanchett in the lead role. Actually, there are no lead roles, it is directed by Thomas Ostermeier. When I was younger and still in the closet, I used to date an actor—he was my best friend, and still is—and we’d travel from Copenhagen to Berlin to see Ostermeier's productions at the Schaubühne. Ostermeier, the enfant terrible, wrestling with old classics like Hamlet and An Enemy of the People, was mind-blowing, addictive, destructive, and truth-seeking.

Last night, something strange happened during The Seagull. It wasn't as good. The German, now middle-aged enfant terrible, the British rigidity of Chekhov’s three kinds of humor and ideas clashing—it wasn’t interesting, just half there. (Ostermeier kills the seagull because he has nothing better to do; he kills it because he can).

On stage, Cate Blanchett is always great, but this time, she seems like she doesn’t want to be there. In this deconstructed landscape, she comes across more as a still image than a moving actress. She poses, afraid to stop moving, so these sequences of poses become a contact sheet of an actress in a midlife crisis (quote play) grappling with aging. (Skin, body, form—a fragility…) Nina or Irina? Or is there something else at play?

Many of Peter Hujar’s subjects never got to grow old; the AIDS epidemic wiped out a whole generation of potential mid-life crises, swaggering old queers, memories, and knowledge of how to live other narratives, other ways of aging—myths that were never passed on. A void, a void that could have been avoided if the world hadn't been so homophobic, xenophobic, and capitalist. (How is it that we are still swimming in this dark pool of ignorance today?)

Charlie Porter writes a fictional yet very real story about this loss of a generation, and about gardening in the shadow of high-rises, in his new novel Novia Scotia House. I went to the launch where he spoke about care and kindness, and how gardening, tending, and volunteering are ways of reconnecting—with community.

That bird, that seagull on the beach—Peter Hujar photographs people and animals with the same intense interest, care, soul-searching, and love. He photographs friends, lovers, dogs, horses, writers, actors, scars, desires, dark waters, empty streets, piers, staircases, holes—holding them in squares where it’s clear, in the present, vibrating, time collapsed without blinking.

The image of the seagull (is it a seagull?) and the images of Cate Blanchett on stage merge. I think Peter Hujar would have photographed Blanchett if he were alive (or at least I would have liked to see him do so). The tonal qualities of his photographs—loss, death, presence, love, and affection—will stay with me for many years. The seagull, growing old, not getting old, the free and the trapped. Which is which?

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

ANTONIA SERRA SANNA

This photograph could trigger many conversations: about the historical role of photography within colonial contexts, such as the one my Island found itself in, about gender matters related to consent and narrative, about the complexities of relations within dominant and subordinate groups with and within archival entities and the power dynamics they enact and often enable at many conscious and subconscious levels, up to the very complex issue of how identity is constructed, both through photography and despite it.

Pezza (sic) Antonia, positivo, 1899. (c) Museo di Antropologia Criminale Cesare Lombroso, courtesy Catalogo Generale dei Beni Culturali.

Afterimage by Elisa Medde:

For a long time now, I have been obsessed with a mugshot from 1899, taken in Nuoro, my hometown in Sardinia. The woman in the photograph, whose identity is somewhat opaque today, was photographed during her arrest. Her image is now part of a collection gathered by Cesare Lombroso, a pioneer in criminal anthropology. His theories on anthropological criminology, race, and genetics had lasting consequences and continue to affect us today.

Sardinia was undergoing massive changes at the time. The move from being subjected to Spanish rule to becoming a possession of the House of Savoy in 1720 meant major social and political changes, amongst which moving from a substantially communal land management to a private property-based economy under the House of Savoy. The 19th century saw periods of intense struggle, famine and upheaval, and also saw the introduction of photography on the Island as a tool of colonial control and documentation. Towards the end of the century, by royal command, every person arrested on the island had to be photographed, and a dossier had to be made following the method Berthillon. Of each photograph 6 prints had to be made, and a large selection of those ended up being used as materials for the “new studies” in criminal anthropology. During one night in 1899, almost 700 were arrested in the centre of the Island. Amongst them, is the “mysterious woman” whose portrait hunts me. Her identity is known on the Island: at the time, she was likely one of the most feared women on the island. Books have been written about her, movies have been made, and legends have been created. She was sister to the two “most feared brigantes of the time, eventually slaughtered by the Royal Forces after the largest police operation chronicled in the century, known as Caccia Grossa (the big hunt). Their massacred bodies were photographed as trophies and exposed to the public gaze, a testament to the power of the newborn Italian kingdom. Sardinia’s stability was key to Italy's unification, and her image reflects the broader political context. This woman was called Sa Reina, the queen, equally feared and admired. After her arrest, her brothers were murdered, she spent some time in jail, was eventually liberated, married someone and died in substantial oblivion. We know that the photograph was taken as part of a specific mass arrest. She’s wearing traditional Sardinian clothing, standing straight in front of the camera. Her expression became an act of defiance and rebellion, unreadable and unforgiving.

This portrait became part of the Lombroso Archive, and it was included (together with other mugshots) in an accordion-shaped display format, used to illustrate Lombroso’s thinking in congresses and symposia. Today, the woman depicted is identified with a name that is not hers. Her name was known at the time, her fame being the reason why she got included amongst some of the most famous male bandits. It is also handwritten in the photographs, now hidden under the passpartout holding them. Yet, in current official documents, her real name has been misrecorded due to confusion with identifying Sardinian surnames.

Pezza (sic) Antonia, positivo, 1899. (c) Museo di Antropologia Criminale Cesare Lombroso, courtesy Catalogo Generale dei Beni Culturali.

This photograph could trigger many conversations: about the historical role of photography within colonial contexts, such as the one my Island found itself in, about gender matters related to consent and narrative, about the complexities of relations within dominant and subordinate groups with and within archival entities and the power dynamics they enact and often enable at many conscious and subconscious levels, up to the very complex issue of how identity is constructed, both through photography and despite it. The photograph and the history of the woman it depicts offer an interesting case study in observing how women’s lives and actions were more often than not depicted in historical accounts - their complexities flattened into dichotomies of passive submissions versus terrifying, evil power. Her story is tied to patriarchal and colonial power structures that still influence how we read our past, and understand our present. She is just one in the very long list of historical figures and individuals fetishized as exotic specimens, hyper-sexualised in their fierce barbarism, forced to become almost mythical figures.

Then there is my favourite part: the photograph’s afterlife, its uses and abuses, its purposes, and the meaning it acquired and lost over time. But this part of the story is for another time. For now, it starts with her name:

Antonia Serra Sanna.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

JAMES BALDWIN AND LEONARD BERNSTEIN

The snapshot quality of the photo, almost like a Kodak moment, adds a sense of relatability. Color clearly plays a key role here, from the rich textured decor to their clothing. Baldwin chose elegant black, while Bernstein dared to wear a white tuxedo with a red bow tie. The flamboyant, gay-ish quality of their attire, paired with the colorfulness, sets the tone in my mind. The queerness, in the true sense of the word (though I find it difficult to embrace how the term has evolved today), is partially present in the pairing of these two larger-than-life figures.

From the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Gift of The Baldwin Family.

Afterimage by Dani Issler:

I was going to choose a catastrophic image, seeing that we are living through a catastrophic era—it seemed more truthful. When I read the description of the Afterimage series, Gaza immediately came to mind. I also thought of Los Angeles, an image of something that consumes itself—fire, catastrophe, and misery. But then I realized that it would be more important for me to present an image that is closer to my own life. This image is my desktop background, and it has been on my computer for about a year. It feels like a tableau, almost like a painting.

On June 19, 1986, American writer James Baldwin and composer/conductor Leonard Bernstein were each awarded the Légion d’Honneur, France’s highest honor, by President François Mitterrand. The ceremony took place at Place de la Concorde in Paris, at what is now a museum, Hôtel de La Marine. It was a symbolic moment: a Black writer who revolutionized literature and Civil Rights, challenging the American status quo, and a Jewish composer who reshaped American music and supported progressive causes.

I came across this image randomly while researching both men. I think I chose it because there's something very amusing about it. As far as I can tell, it’s a candid 35mm shot. There’s intimacy between the two men in the foreground. Bernstein looks like a Bar-Mitzvah boy, only recently out of the closet. This could even be a photo of a Gay marriage avant la lettre. In other photos from the event, they both seem genuinely happy and more relaxed than ever before. It was also a rare moment when Baldwin was honored outside of the U.S., where his work was often controversial. The fact that he and Bernstein—both gay and deeply involved in Civil Rights causes—stood together to receive this award is a powerful image of artistic and political solidarity. There’s also a kind of melancholy that I project onto that moment: Baldwin would die one year later, 1987, and Bernstein shortly after in 1990, at the height of the raging AIDS pandemic, where many Gay cultural icons and thinkers were struggling for their lives, often perceived melancholically in black and white images (I’m thinking of Hervé Guibert’s intimate portraits, such as that of Michel Foucault).

The snapshot quality of the photo, almost like a Kodak moment, adds a sense of relatability. Color clearly plays a key role here, from the rich textured decor to their clothing. Baldwin chose elegant black, while Bernstein dared to wear a white tuxedo with a red bow tie. The flamboyant, gay-ish quality of their attire, paired with the colorfulness, sets the tone in my mind. The queerness, in the true sense of the word (though I find it difficult to embrace how the term has evolved today), is partially present in the pairing of these two larger-than-life figures. It feels like they are on a stage and the human backdrop (predominantly women) adds character and liveliness to this casual, yet festive scene. I can spot Baldwin’s brother and his elderly French housekeeper from Saint-Paul-de-Vence who was close to him, and this moves me, that she accompanied him there.

For me, it’s a symbolic event—a ceremony that could represent an alternative existence in time. This moment of happiness is also tied to the trope of ‘an American in Paris,’. Although I am not American, I can certainly relate to the idea of expatriatism, especially in today's context – as we bear witness to the decline of the Pax Americana. Under Trump the American experience in Paris, as particular and privileged expatriatisms as it may be, feels more relevant. Paris was and still is a real place, even for Americans. As Oscar Wilde summed it up in The Picture of Dorian Gray:

‘They say that when good Americans die, they go to Paris.’

‘Oh, and where do bad Americans go?’

‘They stay in America.’

This photograph captures a fleeting moment of joy, camaraderie, and recognition—an afterimage of history. I’m tempted to title it Glitter and Be Gay, which is the title of the famous coloratura aria from Bernstein’s comic operetta adaptation of Voltaire’s Candide (1956). A critique of false optimism, war, religious hypocrisy, and human cruelty – ideas that feel just as relevant today. This aria is a satire of aristocratic excess and female suffering, blending irony, musical brilliance, and theatricality.

Glitter and be gay,

That's the part I play;

Here I am in Paris, France,

Forced to bend my soul

To a sordid role,

Victimized by bitter, bitter circumstance.

[…]

Enough, enough

Of being basely tearful!

I'll show my noble stuff

By being bright and cheerful!

[…]

Observe how bravely I conceal

The dreadful, dreadful shame I feel.

*Listen and see Bernstein conducting this aria here.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

CAROL NEWHOUSE

‘Is it possible to leave everything behind? Is it possible to begin again, outside and beyond every system of living you've ever known, reinventing what it means (and looks like) to exist as a body and soul on the land?’ These questions shaped Carmen Winant's exploration of radical reinvention, particularly within the context of the lesbian separatist communities of the 1970s.

Carol Newhouse, self-portrait from an Art and Photography Workshop, Womanshare, summer 1975.

For this year's Les Rencontres d'Arles, Objektiv's editor Nina Strand curates the exhibition Double with Carol Newhouse and Carmen Winant, featuring this image by Carol Newhouse as her current afterimage.

‘Is it possible to leave everything behind? Is it possible to begin again, outside and beyond every system of living you've ever known, reinventing what it means (and looks like) to exist as a body and soul on the land?’ These questions shaped Carmen Winant's exploration of radical reinvention, particularly within the context of the lesbian separatist communities of the 1970s. Through this process, Winant connected with Carol Newhouse, co-founder of Womanshare, a lesbian feminist community on the West Coast of the United States. Winant’s and Newhouse’s ongoing dialogue has evolved through several collaborative projects that examine the transformative impact of feminist movements from that era, viewed through the lens of Newhouse's photographic practice and archive. The medium became an essential tool for Newhouse, allowing her to assert and control her own representation.

For Les Rencontres d'Arles, they've created unique new work that weaves together their stories, passions, and curiosities. Over the course of a year, they engaged in a photographic dialogue—one would shoot a roll of film, wind it up, and send it across the country, where the other would expose it once more—using the technique of double exposure to create a layered interplay between their images. Double exposure was a technique used by Newhouse and her comrades to play with the singularness of pictures, or the claim of a single (often masculine) art creator.

Through this creative collaboration, the artists reclaim feminist photographic strategies. With a fulcrum in a series of images by Newhouse from the very beginning of the community, Winant and Newhouse invites us to consider how we reinvent ourselves and our histories—both individually and collectively—through the act of self-representation and interconnection. Their visual conversation delves into intergenerational relationships and feminist political legacies while bringing the experimental photographic practices of the past into the present.

BILLY MEIER

From the very beginning of photography things have been altered, making people believe false narratives. For instance, many believe Communist Russia propaganda photography was full of people drinking champagne, but in reality, they were just sitting around empty tables. If you asked me to draw a photograph, it would probably look something like this. It encapsulates everything that photography stands for—and everything that's problematic about it. It’s about the idea of evidence, but photography is arguably one of the worst mediums for documenting an event.

‘UFO’ sighting by Billy Meier.

Afterimage by Oliver Griffin:

Last February I did a residency at the Andreas Züst Library in Switzerland. I found that most of the photographic records of UFOs in the country were taken by a Swiss farmer, Eduard 'Billy' Albert Meier, just outside Zurich in the seventies. The images are beautiful, and every time you look at one, it evokes the idea of what a UFO encounter should be, in the Hollywood sense—not as a horror story, but more as a captivating experience. It’s the kind of encounter that makes you want to believe in a truth beyond our world.

I first saw one of these images in the 1983 book UFO…Contact from the Pleiades by Brit Elders & Lee Elders and something about the composition, the landscape, and the idea of an object floating and observing caught my attention. The stories behind his ‘encounters’—which lasted for much of his life until the end of the seventies when the aliens supposedly stopped contacting him—fascinated me. By then, he had an international UFO religious organisation with followers in the US, Mexico, and Europe. Despite Meier’s fame, he was a recluse, never leaving Switzerland. His photography and filmmaking were extraordinary, and this particular image still haunts me. It feels so ordinary, as if you were on a form of transport, traveling through a familiar landscape, and in the background, you spot a UFO floating quietly.

There’s a crazy history behind Meier. He ran away from Switzerland, joined the Foreign Legion, escaped again, lost an arm in Turkey while riding a bus back to Switzerland, and eventually ended up with a farm where he shot everything. He then claimed to have communication with an alien race over five years, with instructions on where to spot UFOs. He used a specific Olympus 35 ECR camera— the one that required winding with your thumb with a wheel —because it was the only camera he could use. He would take his motorbike up the hill to shoot these photos. Ironically, one of his images was used for the infamous X-Files TV series poster. When you think of TV series, popular culture, and aliens, you probably think of the iconic X-Files image, and Meier’s photograph is the one featured in the back of Fox Mulder’s office. It became the popular cultural representation of what a UFO should look like.

What’s fascinating is that Meier, who didn’t seem to want much, kept taking these photographs of aliens. It was later revealed that he actually made these aliens himself, using various bits of scrap metal on his farm and polishing them up as models. Some of these models occasionally pop up on eBay, not for much money. There’s a whole typology of different alien crafts and there supposed capabilities.

From the very beginning of photography things have been altered, making people believe false narratives. For instance, many believe Communist Russia propaganda photography was full of people drinking champagne, but in reality, they were just sitting around empty tables. If you asked me to draw a photograph, it would probably look something like this. It encapsulates everything that photography stands for—and everything that's problematic about it. It’s about the idea of evidence, but photography is arguably one of the worst mediums for documenting an event.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

JONI STERNBACH

What fascinated me about the image was learning that Joni wasn’t a surfer herself. She initially began photographing the sea because of her interest in water and its environmental significance. She had no intention of photographing surfers, but eventually, she was drawn to them. Her tintype process, which was such a spectacle on the beach, led her to engage with surfers and over time, she developed a connection with them, photographing them in a way that speaks to both the vulnerability and strength of their characters.

Joni Sternbach, 16.02.20 #1 Thea+Maxwell, Unique Tintype, Santa Cruz, CA 2016.

Afterimage by Christiane Pratsch Monarchi:

The image that captivates me is a tintype by Joni Sternbach, which won second place in the Taylor Wessing Photography Portrait Prize in 2016 out of over 4,300 entries. The image itself is fascinating because it combines a traditional photographic process with a contemporary subject. It features a young surfer couple, exuding relaxation, poise, and trust—qualities that elevate them into monumental representations of virility and youth. The composition is emotionally charged, evoking different narratives: perhaps they are returning from surfing or heading out to the sea, deeply in love, or simply enjoying the beauty of their bodies and the moment.

Growing up in America on the Gulf of Mexico, there was no surfing where I lived—just underage drinking and cars driving in circles. I always longed for that surf culture but didn’t experience it until much later in life. In my 40s, I learned to surf with my kids and husband in North England, and I’ll continue to do so for the rest of my life. There’s something incredibly special about surfing that has always drawn me in, and it connects deeply to my personal memories.

What fascinated me about the image was learning that Joni wasn’t a surfer herself. She initially began photographing the sea because of her interest in water and its environmental significance. She had no intention of photographing surfers, but eventually, she was drawn to them. Her tintype process, which was such a spectacle on the beach, led her to engage with surfers and over time, she developed a connection with them, photographing them in a way that speaks to both the vulnerability and strength of their characters. The trust and relaxation they exhibited in front of her camera transformed them into monumental figures, full of gravitas. The tintype process itself—so different from digital photography—adds to the timeless, object-like quality of the image. It’s a piece of art that will endure, much like the surfboards she photographs, which have their own monumental significance.

Making a tintype is an amazing process. I did it once in a workshop, and it’s highly controlled. The process is meticulous—you coat the plate, handle it with care, and expose it to just the right light. It requires a very specific environment, which makes Joni’s work even more impressive. She’s out there on the beach, doing something that typically requires a controlled setting, and that adds a level of fragility to her work. The wind, the elements—all of that interference creates beautiful imperfections in the final images, which I find fascinating. Joni’s ability to do all this on the beach, with such an unstable process, adds another layer of complexity and beauty to her work.

The beauty of Joni’s work lies in the diverse subjects she captures. Some of her other images feature older surfers or women with different body types, showing that surf culture isn’t just about the typical image of young, athletic individuals. There’s something timeless and humanizing in the way she captures people from all walks of life. The image I selected might be more traditional, featuring a young, blonde, athletic couple, but it’s the one that I couldn’t stop staring at. It’s a fabulous piece.

This image also seems to capture a specific moment in time—a snapshot from before things changed. It was taken in 2016; since then I’m not sure how Santa Cruz has been affected by wildfires but it's such a difficult time. Despite the challenges they face, these people are still going out to surf, living their way of life. It’s a time capsule, a reminder of a different era, and that’s something I find incredibly poignant. It’s not just about the photograph itself, but about the process and the environment in which it’s made. It’s also a beautiful portrait of a culture that is not just about surfing, but about a way of life.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

ANDREAS FEININGER

Because of its ambiguity, several ideas bounce around. The most immediate is seeing and thinking about the activities of the photographer. This much is immediately visible: how the camera mediates (obscures and also complicates) the photographer’s relationship to the world. It’s surprising: we see the photographer, but there’s an imbalance or a merging with the machinic, with the apparatus in the foreground. Of course, this is often how it is – the photographer says they step back for the photograph to function as truth. But here the photographer’s way of looking is shaped by this object that they’re seeing through, they are transformed by it. And in case we forget, we’re seeing them with a similar device. Feininger would also build his own cameras, so he’s conscious of the act and the construction, and so should we. How do we recognize what’s happening in an image? That the picture is not just a window; but a vision, a translation, an act of looking shared with us? That’s another thing.

Andreas Feininger, The Photojournalist (Dennis Stock), New York, 1951.

Afterimage by Duncan Wooldridge:

This is an image that keeps coming back to me; it comes out of nowhere, resurfaces; it always feels relevant. The photograph was made by Andreas Feininger and is called The Photojournalist. There's some debate about when it was taken: many examples are dated as 1951, whilst MoMA has a print with a subtly different point of view which it dates to 1955. Pragmatically, exact dates don’t matter in this image that much – it’s not an image of an event - but imaginatively it feels fitting: it’s a strange document, an image of someone who a viewer might think is a time-traveller, before Chris Marker’s La Jetée. But it's also a portrait, an image of the Magnum photographer Dennis Stock. It is a document with one foot in fiction, a bit post-human. And it makes me think about what photography does.

Because of its ambiguity, several ideas bounce around. The most immediate is seeing and thinking about the activities of the photographer. This much is immediately visible: how the camera mediates (obscures and also complicates) the photographer’s relationship to the world. It’s surprising: we see the photographer, but there’s an imbalance or a merging with the machinic, with the apparatus in the foreground. Of course, this is often how it is – the photographer says they step back for the photograph to function as truth. But here the photographer’s way of looking is shaped by this object that they’re seeing through, they are transformed by it. And in case we forget, we’re seeing them with a similar device. Feininger would also build his own cameras, so he’s conscious of the act and the construction, and so should we. How do we recognize what’s happening in an image? That the picture is not just a window; but a vision, a translation, an act of looking shared with us? That’s another thing.

The next is its strangeness, the light and shadow, the shroud of the cap. The who of the image: even if we have no access to the knowledge that it is Stock who Feininger is photographing, there is the title, The Photojournalist. Anonymised, an archetype ‘The photojournalist’. Is the photojournalist human? Are they like us? It seems to be posed as a question. As we look to the eyes, we have two optical devices: the lens and the scope on top of the camera in their place. The two ‘eyes’ are not the same. They’re a pair, interrelated, but not identical. Equivalence or balance is complicated. For me, this is telling about an important relationship we should have with photography—it’s not exact reality, but a negotiation with it, a very contingent and powerful one.

The fictions I enjoy aren’t fantastical or detached from the tangible. I’m interested in that kind of Jose Saramago or Clarice Lispector sense of something happening, becoming. In Saramago that is "what happens if the world was different in just this one respect?"— what are the consequences of subtle shift? What moves our position, our way of seeing the world? This image lets us think approach those concerns, even if this pushes up uncomfortably against the photojournalist’s conventional claim to objectivity, to reporting. Maybe that’s because the old fact and fiction duality just isn’t working anymore.

Astill from Chris Marker’s La Jetée, 1962.

As a document with one foot in fiction, we can expand our perspectives. Stock is photographing us with a rangefinder camera, probably a Leica. And we can see that he is seeing us through a scope or viewfinder that sees a different world. The rangefinder, as opposed to a single-lens reflex, has two positions: one position from which the camera operator sees, and a second which is the view that is exposed onto film. The machine and human operator see differently. Though the camera and viewfinder are configured to minimise the disconnect, a difference can be seen under careful observation. It’s called parallax. I’m interested in parallax as the actual and poetic optical event that is happening here, in this portrait and in fact in all photographs. Stock is looking through the scope and seeing one thing, and the lens is seeing another. This opens up a potentially radical possibility: photographs can modify the world. They are showing us emergent possibilities, for good and for bad. This allows us to think about how the world is given form, in-formed by our looking. Just think how much the world been changed by the presence of photographs! Has the time-traveller returned to remind us?

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

ELLE PÉREZ

This book gathers a decade of celebrated artist Elle Pérez’s reflections around photography. A collage of loose thoughts, letters, press articles and reviews, text messages, pictures, sketches, responses, emails, notes, and lectures, the book explores what Pérez chooses to photograph and what photography means to them. It is a tapestry of personal insights, intimate moments, and candid reflections, all woven through the medium.

This book gathers a decade of celebrated artist Elle Pérez’s reflections around photography. A collage of loose thoughts, letters, press articles and reviews, text messages, pictures, sketches, responses, emails, notes, and lectures, the book explores what Pérez chooses to photograph and what photography means to them. It is a tapestry of personal insights, intimate moments, and candid reflections, all woven through the medium.

Objektiv Press was founded in 2009 and began as a biannual journal of lens-based art. After ten years of exploring this format, we transitioned into a more book-like publication, where we let just one writer fill the pages with their real and raw opinions, writing about different trends within the medium.

Since 2020, we have been inviting different people—photographers, critics, curators—to reflect on their relationship with photography through a longer essay. We want to deepen our content and continue to explore the development and position of film and photography both in the art scene and in society.

YOLA BALANGA

I long to join the surfers in a diptych I pass. It could offer a needed pause, but politics continue, in another two-work collage showing two women sporting large headpieces full of images from different manifestations. This is what many carry, symbolisingthe worry that never ends, the protest that never rests. The large blue Post-it note with the words ‘Technically, this piece can be considered a painting’ and the smaller red one on the side, stating ‘Not for sale (edition of 3)’ offer some smiles, as do the men in large pink kaftans and the women in gold- and silver-embroidered dresses flâneuring around the fair, champagne in hand, only there to be seen. They might pass quickly by the work in a triptych depicting a woman crawling out of a too-tight cave, and what I will carry with me is the artist’s quote on how Nature is a Black Woman.

Afterimage(s) by Nina Strand:

Yola Balanga, from the series Born of the Earth.

The word ‘fuck’ on a pink painting is the first thing I really notice while walking around the Cape Town Art Fair for the second year in a row. The word, written on the hand-colored paper, sums up many of my feelings after just having seen the return of the fascist salute for the second time in such a short span of time.

We are, in some ways, at rock bottom. The past has become the present. I watched the film on Lee Miller on the plane here and was reminded of her reportage Believe It, published in Vogue in June 1945. Her haunting documentation from a concentration camp proved what really happened during World War II. Have we learned nothing? We didn’t. Apartheid was established in 1948. I’m confronted with blurry Holga camera images in black and white from the site of multiple executions of political opponents listed by the Afrikaner government in this town. It faces a collage featuring a floating black woman’s head in a blonde wig, surrounded by objects like a pant line and a cartoon rabbit. It hurts. We are all fucked.

I can’t stop thinking of the suffering here—officially ended in ‘94, but still. I am the tourist. Always. Just like when I visited Vienna and, while passing the art academy, thought of what might have been avoided had he been accepted there. I think of how Elon Musk’s grandparents emigrated from Canada to this country in support of apartheid. Musk holds Canadian citizenship through his mother, Maye, who was born in Canada. Now, many Canadians are signing campaigns to remove his citizenship. They don’t want him, and I’m guessing this country doesn’t either.

I long to join the surfers in a diptych I pass. It could offer a needed pause, but politics continue, in another two-work collage showing two women sporting large headpieces full of images from different manifestations. This is what many carry, symbolising the worry that never ends, the protest that never rests.The large blue Post-it note with the words ‘Technically, this piece can be considered a painting’ and the smaller red one on the side, stating ‘Not for sale (edition of 3)’ offer some smiles, as do the men in large pink kaftans and the women in gold- and silver-embroidered dresses flâneuring around the fair, champagne in hand, only there to be seen. They might pass quickly by the work in a triptych depicting a woman crawling out of a too-tight cave, and what I will carry with me is the artist’s quote on how Nature is a Black Woman.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

AMANDA WASIELEWSKI

I’ve generated many different images, and there’s always something interesting that comes through. I think many commercial AI tools are refined repeatedly to become more and more standardized, so users get what they expect and no longer encounter strange, unexpected results. The commercial tools don’t want weird stuff. But in terms of an art practice, what’s most interesting to me are the weird things—the fragments, the mistakes, the artefacts of what's happening within the model to generate these images based on whatever associations the words in the prompt carry.

Image generated by Amanda Wasielewski.

Afterimage by Amanda Wasielewski:

I’ve generated a lot of AI images for both my research and also my art practice, it is driven by curiosity and exploration. I created this image about a year and a half ago, and I keep coming back to it. The prompt was inspired by the famous line from The Songs of Maldoror by Comte de Lautréamont: "…as the chance juxtaposition of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table!" This line was crucial to the Surrealists because it spoke to the unexpected chance encounters of objects, and I wanted to see what an AI tool would generate from that.

What intrigued me was the unexpected appearance of a weird object on the left side of the image. The sewing machine and umbrella are represented here, though not quite as I envisioned, but then there’s this other object. It is the most uncanny part of the image. It looks like some kind of medical equipment stool covered in periwinkle, shiny fabric, something you’d expect a surgeon to wear in an operating room, but it has a metal pan on top. I kept coming back to this odd object, wondering what it means, why it’s there, and how it was conjured. It feels like fragments of associations, visualized through the AI model based on the prompt. For instance, I wanted an operating table or surgical table, but what I got was something closer to a sewing table. Still, the surgical part comes through with this strange figure that seems to have wandered in from the side.

I was thinking about what kinds of pixel fragments or textures the model associates with specific words. It’s a mistake, but it’s also evocative in this weird, uncanny way. The more you look at it, the less you understand. I could point out other absurdities in the image, like the umbrella being both a rain umbrella and an outdoor patio umbrella, or the lamp hanging from nothing. These are weird, but not inexplicable like this stool which feels more unknowable.

I’ve generated many different images, and there’s always something interesting that comes through. I think many commercial AI tools are refined repeatedly to become more and more standardized, so users get what they expect and no longer encounter strange, unexpected results. The commercial tools don’t want weird stuff. But in terms of an art practice, what’s most interesting to me are the weird things—the fragments, the mistakes, the artefacts of what's happening within the model to generate these images based on whatever associations the words in the prompt carry.

There’s something about how we want to trust and believe in images, no matter the medium. We’ve had years of easy image alteration—from Photoshop to social media filters—and yet, we still want to believe in what we see. I look at these images, and it’s so obvious, how could anyone possibly believe in them. But I think we still want images to communicate truthfully, and that’s something I find interesting. Over time, those images will become less creepy, and I think that will cover up or beautify the weirdness. But right now, we’re in this moment in image culture where we can still see the oddities before they’re smoothed over.

Wasielewski is Associate Senior Lecturer of Digital Humanities and Associate Professor (Docent) of Art History in the Department of ALM (Archives, Libraries, Museums) at Uppsala University. Her research focuses on the use of artificial intelligence tools to study and create art and images.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

ED THOMPSON

It’s not so much an image in my mind, but something I’ve seen all my life—an optical phenomenon. I often wonder, psychologically, when I first became aware that I was seeing something no one else did—and how that shaped my understanding of reality. After all, seeing is believing, right?

Image by rawpixel.com.

Afterimage by Ed Thompson:

It’s not so much an image in my mind, but something I’ve seen all my life—an optical phenomenon. I often wonder, psychologically, when I first became aware that I was seeing something no one else did—and how that shaped my understanding of reality. After all, seeing is believing, right?

It was probably around 1984, lying in my parents’ bed in Wales—though I’m not sure why. Maybe they put me there to help me sleep. I remember shouting downstairs because I couldn’t sleep due to the lights, and they came in, but when they did, the lights were off, and they didn’t understand what was going on. If I focus now, I can still see those lights, like they’re in the palm of my hand or on your head—like an LED laser sight.

Years later, I was diagnosed with an optical anomaly: a cluster of lights at the center of my vision, like the static on an old TV set but in bright colors. I’ve learned to ignore it, but I can still choose to see it whenever I want. It’s small, but it flickers in every color of the rainbow—constantly shifting, never still. I don’t know when my brain learned to ignore it, but there must have been a time when I couldn’t shut it off, and it was always there. I can’t say how that affected my visual perception or what I believed I was seeing. I have no memory of when I realized no one else saw it, but I know it’s always been there. People may not see what I see. I’ve come to realize I’m literally hallucinating all the time, and the opticians just call it an anomaly.

I’ve had students with similar experiences. One, Sarah, had vision problems that caused her to see things differently. She created a photography project to show how she saw the world when she wasn’t looking directly at things.

As a photographer, I’m acutely aware of how subjective photography is. That’s why I love documentary photography. It’s beyond my imagination. If you're limited to your own imagination as a photographer, you’re just illustrating ideas. But when I pick up my camera, I feel like a conduit—capturing the weirdness around me. I never know what will happen. A lot of the time, I wonder: When you’re on the edge of something, are you actually onto something? Artists like William Blake and other visionary figures believed their visions were real, I feel the same way about my work.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

SEMANA

It is a widely circulated magazine in Colombia, much like Der Spiegel in Germany. The image is from 1985, and I kept the cover, though I’m not sure why. I was eight years old when I first saw it. The picture shows a building in flames, with the title reading 28 Hours of Terror. The building is the House of Justice, home to Colombia’s Supreme Court, burning to the ground. For me, this event is particularly significant for two reasons: first, because my father was a lawyer, and second, because the impact of what happened changed Colombia forever.

Afterimage by Jorge Sanguino:

Semana is a widely circulated magazine in Colombia, much like Der Spiegel in Germany. The image is from 1985, and I kept the cover, though I’m not sure why. I was eight years old when I first saw it. The picture shows a building in flames, with the title reading 28 Hours of Terror. The building is the House of Justice, home to Colombia’s Supreme Court, burning to the ground. For me, this event is particularly significant for two reasons: first, because my father was a lawyer, and second, because the impact of what happened changed Colombia forever.

In Colombia, any major legal case had to be handled in the capital. All significant cases ended up in this court, the Supreme Court, located in the heart of Bogotá. In front of the building stood the parliament on one side, the cathedral on another, and the mayor’s office on the third. This is the main square of Bogotá, and by extension, the central plaza for the entire country.

During the siege of the building by the M-19 guerrilla group, the army responded by retaking the building with fire and bullets. An investigation into the events is still ongoing, though it may never be fully resolved. During the retaking of the palace, the military entered the building and forcibly removed many people—allegedly labeling them as communists—who later disappeared. The families of the employees who were inside that day still have not found their loved ones. The full story remains untold.

Alfonso Reyes Echandía, a magistrate of the Supreme Court and a friend of my father, addressed the president, asking the military and the government to cease fire in order to start a dialogue. The president never responded to this call. Instead, the military indiscriminately bombed the palace, with people trapped inside.

I remember this as one of the first times I saw my father cry. His generation was very socially engaged when they studied, fighting for social justice. It must have been hard for him to lose so many friends with a similar mindset. In Colombia, it’s difficult to change the country; it’s tough even for politicians. But at least there’s the judicial system, the third power, with the Supreme Court, where you can propose decisions to protect the people and the environment. Around the time this image was taken, Colombia was one of the first countries to propose a complex system for environmental protection. But that generation was lost in the terror, and I think that’s why I kept this magazine.

We may never know all the details of what happened, as I’ve described in the image, but it remains a powerful and haunting portrayal of terror.

Growing up in a country marked by so much violence—a violence often told through stories, rather than images, because there were so few—it’s been hard for those who work with memory and reconciliation. 1985 was the moment when that generation lost confidence that they could rebuild the country. After that, everything in Colombia just got worse.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

OLI SCARFF

I’ve always been drawn to images taken in or under water, and to stories related to water. When I was growing up, my favorite book was The Water Babies by Charles Kingsley. The idea of submersion and drowning has always fascinated me. Drowning is such a strange word because it’s often used in a very pragmatic, negative sense, referring to literal drowning or death. But we also use it metaphorically, to convey a depth of feeling—like ‘drowning in ideas,’ ‘drowning in emotions,’ or even ‘drowning in money.’ There’s a complexity to this idea that I think is reflected in the image. It almost looks choreographed, and it reminds me of some of my favorite photographic series, such as Larry Sultan’s Swimmers, which I study frequently—those underwater shots taken in public pools.

Oli Scarff/AFP via Getty Images

Afterimage by Lou Stoppard:

This image was taken in the summer of 2022 during the World Aquatics Championships in Budapest. The U.S. swimmer Anita Alvarez fainted or lost consciousness while performing. The photograph was taken by Oli Scarff, a press photographer present at the event. What I find so beautiful about the image is, first, its dream-like quality. The softness of her limbs in the water conveys fragility. The two bodies entwined looks almost like a scene from a Renaissance painting. But there's also something else—a real sense of tenderness and transcendence.

I’ve always been drawn to images taken in or under water, and to stories related to water. When I was growing up, my favorite book was The Water Babies by Charles Kingsley. The idea of submersion and drowning has always fascinated me. Drowning is such a strange word because it’s often used in a very pragmatic, negative sense, referring to literal drowning or death. But we also use it metaphorically, to convey a depth of feeling—like ‘drowning in ideas,’ ‘drowning in emotions,’ or even ‘drowning in money.’ There’s a complexity to this idea that I think is reflected in the image. It almost looks choreographed, and it reminds me of some of my favorite photographic series, such as Larry Sultan’s Swimmers, which I study frequently—those underwater shots taken in public pools.

I think my fascination with the image is to with the combination of delicateness, elegance, and drama. It’s full of contradictions in that it depicts a very fraught event, but reads as a very still, slow moment. There’s a lingering sensation about it that I find incredibly beautiful.

As a child, I loved swimming. I was a competitive swimmer and spent a lot of time underwater. There’s a sense of suspended feeling when you’re submerged, like a suspension of sound. I’ve never been able to meditate—I'm too much of an overthinker —but for me, swimming, that hum you get in your ears when you’re submerged, offers a kind of meditation. It’s the feeling that you can disappear. I would spend hours in the pool as a child, diving as low as I could, letting my body float. I think the sensation of floating and being held by water—it’s such an unusual sensation, isn’t it? Obviously, she’s literally unconscious in this moment, but I remember play-acting at something similar as a child—diving under the water and letting myself be still, without intention, allowing my limbs to flail, almost playing-dead. There’s a way of letting go and floating in the water that’s deeply freeing. So I think I also really feel the sensation of the image, which is a strange power it has. I can almost feel the bodily aspect of it. Since I first saw it while reading the news, it has become an image I think about constantly and return to often—not just for its beauty, but for the feelings it evokes.

What’s also fascinating is that, when you think of the language of competitive sports photography—the context in which this image originated—you don’t typically think of poetic imagery. Sports photography is often very visually arresting, striking imagery. But I think maybe the poetry and stillness in this image was actually quite striking for many. There’s something about it that feels almost like a scene from a Disney movie or a love film as it evokes the idea of being saved, which is one of the most romantic concepts there is.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.

RUTH ORKIN

I find a seat on the terrace of a small café in the garden and take my notebook and pencil out of my bag. The photograph The American in Italy is on my mind. While many have described the image as a symbol of sexual harassment, the woman depicted told a journalist that it represented female empowerment. She owns the situation, she claimed. Still, for many, the photo serves as a stark example of how risky it can be for a woman out in the world.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

Ruth Orkin, American Girl in Italy, Florence, 1951.

I find a seat on the terrace of a small café in the garden and take my notebook and pencil out of my bag. The photograph American girl in Italy is on my mind. While many have described the image as a symbol of sexual harassment, the woman depicted told a journalist that it represented female empowerment. She owns the situation, she claimed. Still, for many, the photo serves as a stark example of how risky it can be for a woman out in the world.

I remember arguing about this image on a date. I tried to explain how merely walking down a street could be a challenge for women. My date claimed the woman in the photograph had said it was wonderful, that she was young, carefree, and the world was her oyster. He laughed when I said that maybe she just didn’t want to go into the complexities of the situation with the journalist. That perhaps she was tired of discussing street harassment or being the example of it in this picture. I became angry, asking him how he could argue with me as a member of the opposite sex. The evening did not go well.

On the table next to me sits a couple who are either on their first or last date. He has put on enough aftershave to last him through the day, if not the week. There's a certain nervous energy in the air between them that makes me curious, but I shouldn't be eavesdropping on their conversation. I should be working. I really want to create a project that will change the way women of my age are represented in our society, but when the waiter finally comes to take my lunch order, all I've done is draw a circle and write the words New Narratives in it.

Afterimage is an ekphrastic series about that one image you see when you close your eyes, the one still lingering in your mind. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can't shake. This column has been a part of Objektiv since our very first issue in 2010.