JASMINA CIBIC

Jasmina Cibic, The Gift (still), 2021, three channel 4K video. Courtesy the artist

Afterimage by Lillian Davies:

In the early 1950s Stalin erected the Palace of Culture and Science in the center of Warsaw as a gift to the Polish people, newly part of his Soviet Union. There’s an Olympic-sized swimming pool inside the 42-floor tower, with a diving well and three platform boards. Jasmina Cibic’s three channel 4K video film, The Gift (2021) opens there, with sweeping color images and sounds of chlorinated water trickling through the drains. In her opening shots, three pre-adolescent girls, hair pulled back tight from their pale foreheads, walk one after another along the pool’s tiled edge. They are dressed to perform and to compete, wearing simple one-piece suits, two in navy blue, one in dark red. A stately piano melody and a cool female voice over accompanies them as they climb metal stairs and await one another at the top of the diving platforms. A dive, a front flip, and a pencil shaped plunge, the athletes pierce the calm surface of the crystal-clear water, finger tips first, or toes, at exactly the same moment, amplifying the cutting sound of a splash. Exuding youth, strength and beauty, like Zeus’s three muses, these young women embody ideals that are beyond themselves. Cibic filmed underwater, and seen from below, the moment they break the surface is like the burst of a firecracker, or three. For a split second after their plunge, they are unique, liberated, swimming slowly to the surface and an inevitable panel of judges.

Cibic’s newest film, unfolds primarily in Paris, inside the French Communist Party Headquarters, a gift from architect Oscar Niemeyer. Here, Cibic’s three male characters, “three gifts,” as she calls them, The Engineer, The Diplomat, and the most handsome, The Artist, played by Downtown Abbey’s Lachlan Nieboer, devise a plan: “We will organize a competition to determine the symbol of our renovated future.” And so it is, that each, speaking in turn of the ideological virtues of architecture, music and art, are put into competition to determine the gift that will appease and reunify an unnamed and divided nation.

Four actresses play a cast of allegorical judges, referred to in Cibic’s narrative as the Four Fundamental Freedoms: from Fear, from Want, of Speech and of Worship (terms borrowed from Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1941 speech aimed to spur American support for entry into World War II). The characters’ dramatic period hair, makeup and clothes — perfectly matched to Niemeyer’s 1971 construction date — are a contrast to the unadorned sobriety of Cibic’s three divers. Cibic’s judges’ polish and dress are reminders of the workings and power of spectacle, performances of gender, seduction and status, that fuel political debate and public opinion. The judges’ exchange begins as a sort of philosophical debate and quickly disintegrates into a battle of practical nonsense—jargon.

It’s a jargon that sounds like art-speak or International Art English, as named in the brilliant Triple Canopy study, that eerily familiar language drained of meaning through translation, repetition and misunderstanding. Each line of Cibic’s script is ready-made, like her characters and soundtrack for this film, pulled from archives, transcriptions and recordings of politicians and artists speaking about the ideologies behind modern artworks:

“Art itself if a gift of the creative spirit.”

“The artist is a political being: alert.”

“Art is not made to decorate apartments. It is a weapon to be used against the enemy.”

Not only historical ready-mades, each element—script, music and sites—of Cibic’s The Gift was given as such. MAC Lyon curator Mathieu Lelièvre Lelièvre cites the French social anthropologist Marcel Mauss whose 1924 essay remains preeminent for studies of gift exchange. For Mauss, gift giving implies a social contract performed in public rituals. There’s a stage, costuming and choreography that Cibic forces us to see. Gift-giving can be a tool of soft power, a political and cultural phenomena she’s been exploring since her exhibition for the Slovenian pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2013.

Joseph Nye coined the term “soft power” in 1990, shortly the fall of the Berlin Wall. For Nye, soft power implies “organizing an international agenda and structuring world politics by using resources of intangible power like culture, ideology and institutions.” Mobilizing art for political ends in other words, though sociologist Alexandre Kazerouni warns, in his recent paper, Musées and Soft Power in the Persian Gulf (2015), that Nye’s soft power is not economic power. It is the intellectual and ideological conception of an artwork that matters, not its market value.

Jasmina Cibic, The Gift (still), 2021, three channel 4K video. Courtesy the artist.

Though Cibic doesn’t mention him by name, Lewis Hyde’s eponymous book, first published in 1983, looms large. Hyde wrote as a poet, for other poets, searching for a history and meaning of gift giving, gift having, in a modern society founded on commercial exchange. His subtitle, How the Creative Spirit Transforms the World, reads like a line of Cibic’s ready-made script. As Margaret Atwood wrote recently in Paris Review, in his book, Hyde seems to be looking for a definition of the nature of art. “Is a work of art a commodity with a money value, to be bought and sold like a potato, or is it a gift on which no real price can be placed, to be freely exchanged?” Atwood asks. She proposes an answer in Hyde’s explorations, perhaps in her own work, something also glimpsed in Cibic’s cinematic ruminations: “Gifts transform the soul in ways that simple commodities cannot.” Stalin may have demanded the labor of ten thousand men to build his palace, but there is freedom in the water, in swimming under the surface. It’s Cibic’s triptych image of her divers’ splash, a sort of momentary escape, that stays in my mind, like a gift.

LOUISE BOURGEOIS

Louise Bourgeois, Cell XXV (The View of the World of the Jealous Wife), 2001. © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2021. Photo: Christopher Burke. Shown at Whitechapel Gallery.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

Louise Bourgeois, who called herself a prisoner of her memories, was three years old when the First World War began, and moved from France to New York two years before the Second. She began to make her self-enclosed structures known as the Cells in 1989. The objects collected within them, which one can only view from the outside, all had a personal resonance and history: ‘Each “Cell” deals with the pleasure of the voyeur’, said Bougeois in 1991, ‘the thrill of looking and being looked at. The “Cells” either attract or repulse each other. There is this urge to integrate, merge, or disintegrate.’

Her work has been on my mind a great deal during the last two weeks. The day Putin decided to begin a war against Ukraine, I visited two exhibitions in London where one could see her cells: The Woven Child, at Hayward Gallery and A Century of the Artist’s Studio: 1920–2020 at the Whitechapel Gallery. The first is a retrospective with a focus exclusively on Bourgeois’ work using fabrics and textiles. The second is a survey of the studio through the work of over 80 artists. Featuring Bourgeois alongside contemporary artists such as Walead Beshty, Lisa Brice, Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Mequitta Ahuja, the exhibition gives a peak into how an artist works. This grand survey also demonstrates how artists can and do make a change for the better in society, making one question whether an international ban on Russian artists is the right approach to take, especially since Putin himself silences those who speak against him.

Today we live in a state of constant crisis, with conflicts being waged all over the world, millions of displaced refugees, and the aftermath of the pandemic. With this in mind, Bourgeois’ microcosms, described by Okwui Enwezor as works that ‘turn life inside out’, have extra resonance. The 'Cells' represent different types of pain, Bourgeois has explained: ‘The physical, the emotional and psychological, and the mental and intellectual. When does the emotional become physical? When does the physical become emotional? It's a circle going round and round.’

MOHAMED BOUROUISSA

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

The couple in the café next to me are either on their first date or their last. It’s difficult to know if they’re shy or bored with each other. They’ve been discussing a friend. I’m hoping he’ll never hear their opinions on how sadly he leads his life. I’m on time and happy for the entertainment these two bring while I wait. My friend arrives late. I still suggest we have a glass wine before we go in, it’s been so long. But he’s in a rush and so I quickly gather my things. He doesn’t look me in the eye.

We begin in a sky-lit room that contains only some speakers and small chairs to sit on. Everything is white. Everywhere is sound. Many voices are shouting the word ‘hara’, used by young people as a warning if the police get too close. I wonder if there’s a warning word I can shout to myself about a friend acting weirdly. The thing is, I didn’t really have time for this exhibition visit. This was his idea. ‘All I do is try to keep it together’, I say to him, or to his hair; his back is turned to me. He looks at the wall text – explaining how the artist uses his work to call attention to young people from ethnic-minority backgrounds – and says one should always compare.

We move further into the exhibition, passing a labyrinthine structure of fences with images of refugees on them. The complicated installation makes perfect sense to me in this tense situation. In the next room, we spend time in front of large photographs hung on only one wall. I am moved by the presence and focus the images acquire when exhibited like this. He says he couldn’t disagree more.

We’ve nothing left to talk about. When we pass a sort of garden planted with very thin trees, they seem embarrassed to be there with us. A man is vacuuming around them, something we’d normally laugh about, but my friend still doesn’t meet my eye. I look at his cap, which is on backwards. Who does he think he’s fooling? It does nothing for his receding hairline.

Does one break up with friends? I wonder if I said something stupid last time we met. This is probably my fault. It usually is. He walks quickly through the final room, which is plastered with too many unframed photographs – too many people’s stories we’ll never hear – and makes his way down the stairs. We usually write a wish and hang it on the Wish Tree placed there, but he doesn’t stop.

If I go back to my studio now, I’ll stew for the rest of the afternoon. I write a wish for his health and hang it on the tree, and go back to the café, hoping the couple is still there.

I can still hear the shouting of ‘hara’ for days afterwards.

Mohamed Bourouissa: HARa!!!!!!hAaaRAAAAA!!!!!hHAaA!!! Kunsthal Charlottenborg 09 Okt 2021 – 20 Feb 2022. Courtesy the artist, Kamel Mennour and Blum & Poe. Installation photos by David Stjernholm.

HIROSHI SUGIMOTO

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Opticks 008, 2018, courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

In a currently closed Paris I saw Hiroshi Sugimoto’s new exhibition at Marian Goodman Gallery, and I spent a long time looking at this beautiful blue work. It was a welcome escape from our lockdown situation.

Sugimoto’s subject matter include lifelike displays in museums of natural history, old American drive-in theaters as well as vast seascapes — as he has investigated time and memory throughout his practice. For him, photography functions as a system for saving memories, it is a time machine.

His current exhibition Theory of Colours at Marian Goodman consists of his new series Opticks. The title of this series is a reference to Sir Isaac Newton’s treatise Opticks, published in 1704. Opticks is according to Sugimoto essentially a series shot using a Polaroid camera, capturing the light that Newton refracted using a prism.

This new body of work is just as meditative as his seascapes. He has previously stated that photography is like a found object. That photographer never makes an actual subject; they just steal the image from the world. But not every photographer has the expertise in finding these ‘found objects’ as Sugimoto.

Known for his precise techniques, long exposures and perfectly composed large format photographs — the philosophical and conceptual aspects of his ouvre is just as important. His photographs reveal the time passing, and the mediums unique ability to render a trace of it.

NICOLE EISENMAN, VANESSA BAIRD & LINN PEDERSEN

Nicole Eisenman, Destiny Riding Her Bike, 2020. Photo Thomas Widerberg. Astrup Fearnley Collection.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There's no place like home

On a painting, a drawing and a photograph.

Linn Pedersen, Kiddo, 2021.

The large painting Destiny Riding Her Bike by Nicole Eisenman has been on my mind since I saw it at the Astrup Fearnley Museum In Oslo a couple of weeks ago. A woman soars off her bike having crashed into a ladder set up against a tree, toppling a man who is trying to save the small cat that intently watches the chance meeting between the two humans. In the March issue of New Yorker, Eisenman explains the image in the article ‘Every Nicole Eisenman Picture Tells a Story’ by Ian Parker. ‘It’s a romantic painting of two people meeting. One is falling off a ladder, and the other is riding a bicycle into the ladder—and popping off the top of the bicycle. She’s flying through the air. And they kind of have their eyes locked on each other. I think it’s very romantic—a Douglas Sirk film still.’ Eisenman explains that the picture is connected to her recent relationship with the art critic and writer Sarah Nicole Prickett, and that the image became ‘this disaster happening, and a kind of romance inside this disaster’. In these days of isolation, I long to meet new people like this, romance or no romance.

Eisenman has mentioned her admiration for the Norwegian artist Karl Ove Knausgaard, to whose project My Struggle Vanessa Baird’s work has been compared. Baird has just published her new book There's no place like home with autobiographical drawings of living with her kids and her mother. Some drawings are accompanied by notes written by her mother about her different needs, reflections and thoughts. When I once interviewed Baird, she told me she called her drawings for short essays, hoping people could get something out of seeing her work. ‘My everyday life is like everyone else's, it's about recognition.’ This book with her mother certainly seems to depict a struggle, to paraphrase Knausgaard. In one drawing, Baird is sweeping a never-ending dirty floor, with several kids around her, while in a corner her frail mother is lying in a bed. On the top she has written: ‘Stuck in genes and affection.’

Another mother and daughter relationship is evoked in the photograph Kiddo by Linn Pedersen, included in her recently opened exhibition Omland at Golsa in Oslo. The image is the imprint left in the snow after her youngest daughter outside their house in Lofoten. It was dark outside, Pedersen tells me, and she was carrying groceries from the car as she walked past this impression her daughter had made in the snow. It reminded Pedersen of a cherub from a Raphael painting mixed with the Michelin man, an astronaut, and craters in the lunar surface. Many of the images in the exhibition are from the north of Norway, where she has moved back with her family after many years in the South. Omland in Norwegian means land surrounding an area, and the exhibition is a kind of rediscovery of her old surroundings, very clearly suggested in two images next to each other, one depicting a mountain and the other a mountain of souvenirs, old business cards, passport photos, notes.

A chance meeting, a daughter taking care of her mother and children, and an imprint of a young child in the snow. All three artists were working with a fulcrum in their own life and family situations, and during these weeks of a new lockdown in Oslo it became for me a triptych almost emblematic of the situation. We just have to make the best of it. And it helps to make or see art.

INDER SALIM

Inder Salim, We All Are Women’s Issues, 2003. Courtesy of the artist.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

In the recently opened exhibition Actions of Art & Solidarity at Kunstnernes Hus (The Artists’ House) in Oslo, there is one image that embodies the title perfectly: We All Are Women’s Issues by Indian performance artist and poet Inder Salim. The photograph is from a performance by Salim in Bangalore, India, in 2003. Salim made himself into a walking billboard to protest against violence against women, using the double meaning of “issue” to show how everyone should take a stand against gender-based violence, and also that all humans come from women. As he writes in an email to me: ‘It was indeed a day-long walk on the roads in Bangalore City in 2003. There was no video possibility in those days, but I got some clicks by friends who accompanied me.’

At that time, he and his colleagues put up around 500 posters in Bangalore, and later on buses and walls in Delhi where Salim currently lives. The poster was also used by the women’s police department in Bengaluru, and by Vimochana, a NGO working for women's issues. Salim used the image as his business card for a long time, and it was also printed on a banner of about four and a half metres. ‘The situation in India, the unfortunate treatment of women’, Salim writes, ‘particularly in rural areas, is very disturbing’.

For the past 30 years, Salim has worked tirelessly within the genre of art as activism, using video and photography as well as other channels to make us look again at the world in which we live. His work deals with bodies, sexuality and gender & queer politics. Last fall Ishara Art Foundation invited to the exhibition Every Solied Page where Salim made a series of eleven different performances under the name Every Page Soiled, to be enjoyed here. As he explains his work: ‘Performance art is not body-centric, but revolves around material and subjectivities of all kinds in our respective presents.’

The exhibition’s press text claims that: ‘solidarity has re-entered the global zeitgeist with resounding force in the last decade. It has driven new thinking focused on countering systemic failures and outright abuses related to climate, economy, surveillance, health, gender and race amongst other issues.’ And it continues: ‘Actions of Art and Solidarity considers the central role that artists play within this historical shift in the new millennium, drawing parallels to synergic cases of the twentieth century.’ Looking at Salim’s career, solidarity has always been present in his performances: ‘Doing posters from my own pocket money was my passion in early days. Nowadays, I put up flags from my terrace with text to highlight different topics in our current situation.’

The latest, from five days ago, has a very simple message: ‘I love you.’

INGRID EGGEN

Installation photo by Ingrid Eggen of her Tranquilshiver #2, 2020.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

This weekend, Ingrid Eggen opened the show CLAIM YOUR SUPERIOR BONE together with Admir Batlak at the small artist-run gallery Noplace. Her three new photographs made me recall a recent FaceTime conversation with a dear friend and colleague who had just attended a vernissage and needed a debrief. She said everyone there had been acting weirdly, and wondered if it was anything to do with her. We analysed the situation for a while, before concluding that it was simply an extreme COVID-influenced version of Norwegian’s general uncomfortableness. (In our opinion, being uncomfortable is the norm for Norwegians.) This made us laugh, since in normal times, exhibition openings are often quite awkward, but in this self-isolating time, they become even more so.

Eggen’s work is concerned with the body and its involuntary actions, the ones we deem irrational. As she once explained in an interview with me, these actions are on a par with affect theory: they turn us away from the rational and towards the notion that something more basic informs our actions, such as muscles, reflexes and instinct. For this new work, she had made three frameless photographs on polytex paper of hands twisted into each other, hung directly on the wall. As she says about the work, this is an attempt at advancement within an anatomical form. Both hands in each image belongs to the same person, but act as if they are from two different persons, with one holding the other back.

The title, Tranquilshiver, along with the unease they convey, reflecting the way we feel at this point in time, made me smile. A tranquil shiver: does that even exist?

CLAIM YOUR SUPERIOR BONE. Admir Batlak & Ingrid Eggen. 21.11.20 – 20.12.20.

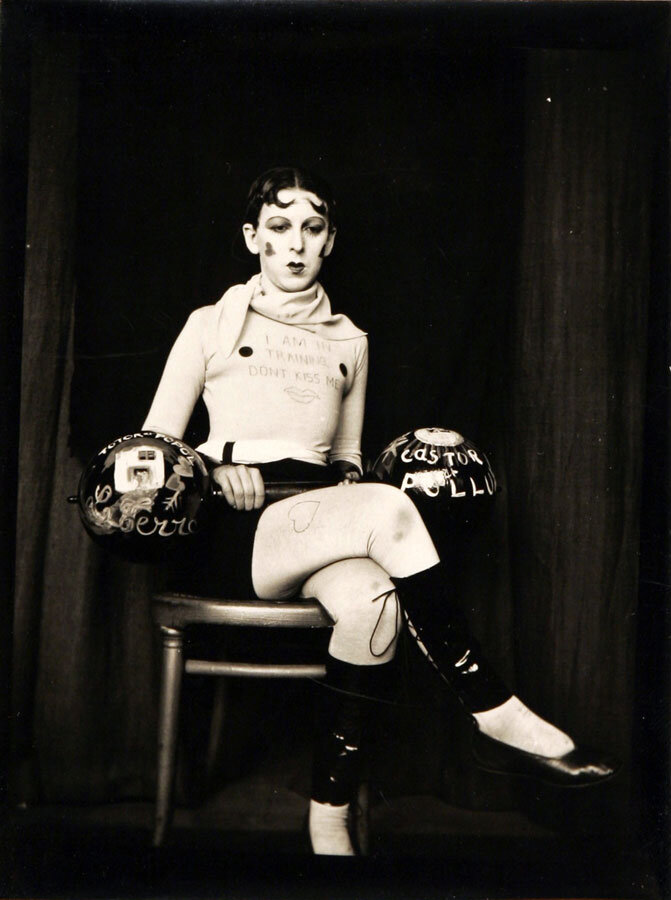

CLAUDE CAHUN

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

This is the last week of Fantastic Women – Surreal World at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, where the work of Claude Cahun, among 34 others, is displayed. Cahun was a pioneer of photography that worked with gender fluidity and identity, and in this sense we owe her a lot. In one self portrait, Cahun is dressed as a weight lifter with the text: ‘I am in training, don’t kiss me’ on her jersey, and a small heart on each cheek, as well as one drawn on her knee. Her quote on gender accompanies the work: ‘Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation.’

It’s almost too much of a coincidence that this show is on at this time in this small Scandinavian country, since it’s been an interesting fall for Denmark. Three years after the MeToo Movement swept over at least the western part of the world, Denmark has finally begun its own investigation into people in powerful positions. A quote by the famed writer Suzanne Brøgger is circulating on social media. She said to the Danish newspaper Børsen that she has no patience with people who complain about MeToo. She doesn’t listen to those inexperienced people who say that women are to blame for their own abuse because they could just say no thank you, dress differently or simply stop putting themselves in dangerous situations. She is at an age where she trusts her own experience, and yet the politician Pia Kjærsgaard is only two years younger, but is one of those who have opposed the movement in Denmark, saying that women must accept advances, and diminishing harassment to simple, innocent flirting. Kjærsgaard claims never to have experienced unwanted attention or sexual advances, and yet she doesn’t hesitate to dictate what other women should put up with. Has she really never been touched by a man without her permission? Luckily, this time she’s outnumbered by many famous men and women, who are standing together, keeping up the momentum of the movement. It all began when the 30-year old TV host Sofie Linde delivered a powerful opening monologue at the TV Zulu Awards, watched by mainly young people, which was the perfect audience to finally hear someone say that enough is enough.

The movement spread quickly from the media world to the art world, giving this exhibition at Louisiana extra importance. If you didn’t catch it, there’s consolation in the fact that this week the great retrospective of the work of Anna Ancher opened at the National Gallery in Denmark. Not a moment too soon.

PROTESTIMAGE

Found via Feminist News on Facebook. Photographer unknown.

Afterimage by Nina Strand:

There’s an image from the recent protests in Poland that I can’t stop thinking about. A woman stands in the middle of a street, in the midst of a demo, wearing a mask and waving a Pride flag in all the smoke and chaos. She seems angry, which is understandable and relatable. Why shouldn’t Polish women be able to decide what happens in their own wombs? It’s 2020 and I can’t believe that we’re here again, with the election of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court putting the American right to abortion in danger, and so the image from Poland hits me. I’m with her in this protest. I’m with her on the issue of choice. It’s vital to me that every single woman gets to decide what to do with her own body. And it’s terrifying how this choice is still being threatened. It reminds me of the image that went viral some years ago, from another protest, of a woman in her sixties holding the sign: ‘I Can't Believe I Still Have To Protest This Fucking Shit.’ She’d obviously done this before. We know that we, and our daughters, stand on the shoulders of our mothers, their grandmothers, who fought for the right to choose. And yet here we are again.

In 2017, I co-curated an exhibition called Subjektiv at Malmö Konsthall showing the work of Josephine Pryde among others, whose series It’s Not My Body shows MRI scans of a foetus in the womb montaged onto colour landscape shots. Pryde hadn’t been intending to take part in any ‘urgent response’-type exhibitions at that specific political juncture, but what caught her attention was another chance to NOT say how it feels to be a pregnant individual. She was interested in describing a shared material state, and included these pieces in the exhibition because she thinks human reproduction is extraordinary and that the history of women as property, as the designated site of reproduction, still haunts our popular mythologies and cultural exchanges. How these ghosts return, how they duplicate themselves and occupy imaginations, is a matter of intense relevance to her, and also to us four years later in these very trying times. So all these thoughts and feelings arise in my mind when looking at the Polish woman waving her flag in Warsaw. I do hope that we won’t have to see images like this in the years to come.

CHRIS KILLIP

Simon Being Taken out to Sea for the First Time since His Father Drowned, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, negative 1983; print 2014, Chris Killip, gelatin silver print. Courtesy of and © Chris Killip. Image from the exhibition Now Then: Chris Killip and the Making of In Flagrante, May 23-August 13, 2017, Getty Center.

Afterimage by Matthieu Nicol:

What image do I have in mind at the moment? It’s difficult to give a quick answer to the question Objektiv has proposed. In my work as a photo editor for the daily press, I see thousands of shots on my monitors every day. This ocean of images, mainly from agencies, formatted, and in the end, very similar, does not help with digestion. Rather than writing about press photos, I want to talk about images or series of images from exhibitions or festivals that has made an impression on me lately. But when squeezing, nothing came out. So I put this question in the corner of my mind for a few weeks, and let it decant. Regularly, like the backwash of a wave, a handful of shots came back; sometimes engulfed but eventually graved in my visual memory. Nothing new, nothing current. So I allowed myself to slightly modify the question: which image, absorbed a long time ago, has stayed etched in my memory and resurfaced regularly?

Among the icons of my “imaginary museum”, there is one that haunts me. A terrible image of infinite sadness but of absolute relevance. In Madrid, February in 2014, an exhibition soberly entitled Work, a retrospective of the work by Chris Killip, was presented at the Reina Sofia Museum. I knew the photographer’s work, and several of his series on the impoverished communities in northern England, the victims of deindustrialization in the early 1980’s in the beginning of Thatcherism. I’d seen them online or in catalogues, notably In Flagrante (1988). But this image was unknown to me because it was absent from the books.

I don’t want to linger on the formal composition of the scene, the position of the body and the closed eyes of the little boy in his Sunday best, floating in adult clothes, his head bent on the line of the horizon, the slight oscillation of a swaying boat, of which only the bow is in the frame. A form of a closed room, without doors or windows, perfectly executed. I would, however, like to emphasise the caption: Simon being taken out to sea for the first time since his father drowned, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, 1983. Everything we need to know is there, in this exact wording. A subject, described by his first name, the reason for his presence, a place, a date. 18 words.

Although the image alone can produce this piercing effect, this “punctum” dear to Barthes, allowing the observer to appropriate it beyond all knowledge, code or culture; the caption gives us information that is essential to our comprehension. What is mind-blowing in this link between text and image is that it reveals the evidence of an extraordinary situation. It enables an immediate comprehension of the degree of commitment the photographer has with his subject. Killip’s approach is unique, the author is distant, out of frame and at the same time, completely immersed in a poignant intimacy. Only the construction of a long- term relationship with this tiny fishing village named Skinningrove, where he documents the daily life of its inhabitants, allows him to produce a scene like this and show it to the world.

With an image so prone to allegory, one could make it say a number of things: a rite of passage into adulthood, filial love, sadness and sorrow. One could also enter into dialogue with other images, I’m especially thinking of the one of Alan Kurdi, the little Syrian boy washed up on a Turkish beach in September 2015. This “shock image” that rapidly went worldwide, became the tragic symbol of the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean. In this reversed perspective we see a small, drowned body and not the survivor, his father, who subsequently testifies of the drowning to international media. Within me, the connection is evident: in my visual memory, these images are contemporary, and as a father of two children the age of Simon and Alan, they move me particularly. But the comparison stops there. We cannot suspect Killip of voyeurism. His restraint, his sense of propriety, his engagement, his empathy are all entirely resumed in this image and its caption.

During a presentation at Harvard University in 2013, where he taught from 1991 to 2017, Killip confides his discomfort on the use of this scene and a few other images taken that day: “I don’ t know how... if I should use these photographs or how I could use these photographs. I’m very unsure about what use they are... ». And indeed, the author dismissed the image from the two editions of In Flagrante (1988 and 2015). During a later conversation held in 2017 at the Getty center in Los Angeles, he clarifies: “In Flagrante means ‘caught in the act’, and that’s what my pictures are. You can see me in the shadow, but I’m trying to undermine your confidence in what you’re seeing, to remind people that photographs are a construction, a fabrication. They were made by somebody. They are not to be trusted. It’s as simple as that.”

En français:

Quelle image ai-je en tête en ce moment ? Il m'a été compliqué de répondre rapidement à cette question, à l’invitation d’ Objektiv. Dans mon travail d'éditeur photo pour la presse quotidienne, je vois passer plusieurs milliers de clichés par jour sur mes moniteurs. Cet océan d'images, principalement d'agence, formatées et finalement fort similaires n'aide pas à la digestion. Plutôt que de photos de presse, j’ai alors cherché à parler d'images ou de séries m’ayant marquées dernièrement dans des expositions ou des festivals. Mais en pressant, rien ne sort. Et j'ai mis cette question dans un coin de ma tête durant quelques semaines, et laissé décanter. Régulièrement, tel le ressac, reviennent une poignée de clichés parfois engloutis mais finalement gravés durablement dans ma mémoire visuelle. Rien de neuf, rien d'actuel. Alors je me suis permis de modifier quelque peu la question : quelle image, assimilée depuis longtemps, est restée gravée dans ma mémoire et refait surface régulièrement ?

Parmi ces icônes de mon « musée imaginaire » il y en a une qui me hante. Une image terrible, d'une tristesse infinie, mais d’une justesse absolue. C'était en février 2014, à Madrid. Une exposition sobrement intitulée Work, rétrospective du travail de Chris Killip présenté au Musée Reina Sofia. Je connaissais le travail du photographe, et plusieurs de ses séries sur les communautés paupérisées du nord de l’Angleterre, victimes de la désindustrialisation à l’aube des années 1980, début du Thatcherisme. Je les avais vues en ligne ou dans des catalogues, et notamment In Flagrante (1988). Mais cette image m’était inconnue, car absente de ces ouvrages.

Je ne souhaite pas m’attarder ici sur la composition formelle de cette scène, la position du corps et les yeux fermés de ce petit garçon endimanché, flottant dans des habits d’adulte, sa tête courbée crevant la ligne d’horizon, la légère oscillation d’une barque qui tangue et dont seule la proue est dans le cadre. Une forme de huis-clos, sans portes ni fenêtres, parfaitement exécuté. Je voudrais en revanche insister sur sa légende : Simon being taken out to sea for the first time since his father drowned, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, 1983. Tout ce que l’on a besoin de savoir y est dit, dosé au mot près. Un sujet, décrit par son prénom, la raison de sa présence, un lieu, une date. 18 mots.

Si l’image seule peut créer cette fulgurance, ce « punctum » cher à Barthes qui permet à celui qui l’observe de se l’approprier, au-delà de tout savoir, de tout code, de toute culture, la légende ici donne une information essentielle à sa compréhension. Ce qui est sidérant dans ce rapport texte-image, c’est qu’il révèle l’évidence d’une situation exceptionnelle. Il permet de comprendre immédiatement le degré d'engagement du photographe avec son sujet. La pratique de Killip est singulière, l’auteur est distant, hors cadre et en même temps, totalement immergé dans une intimité poignante. Seule la construction d’une relation de long terme dans ce village de pêcheurs nommé Skinningrove dont il documente au long cours la vie quotidienne des habitants, lui permet de produire une telle scène et de la donner à voir au monde.

On pourrait faire dire beaucoup de choses à cette image qui se prête facilement à l’allégorie : celle d’un rite du passage à l’âge adulte, de l’amour filial, de la tristesse et du deuil. On pourrait également la faire dialoguer avec d’autres. Je pense en particulier à celle d’Alan Kurdi, ce garçonnet syrien échoué sur une plage turque en septembre 2015. Cette "image-choc", qui a rapidement fait le tour du monde, est devenue le symbole tragique de la crise des migrants en Méditerranée. Dans un retournement de perspective c’est ici un corps de petit noyé, mort, que l’on voit, et non le survivant, son père, rescapé, qui témoigne après-coup de la noyade auprès des médias internationaux. En moi, le lien est évident : dans ma mémoire visuelle, ces images sont contemporaines, et en tant que père de deux enfants de l'âge de Simon et d'Alan, elles m'émeuvent particulièrement. Mais la comparaison s'arrête là. On ne peut pas soupçonner Killip de voyeurisme. Sa retenue, sa pudeur, son engagement, son empathie sont tout entiers résumés dans cette image et sa légende.

Lors d’une présentation à l'Université Harvard en 2013, ou il a enseigné de 1991 à 2017, Killip confie sa gêne sur l'usage qu'il pourrait faire de cette scène et des quelques autres images réalisées ce jour : « I don’ t know how... if I should use these photographs or how I could use these photographs. I’m very unsure about what use they are... » Et de fait, l’auteur a écarté cette image de ses deux éditions d'In Flagrante (1988 et 2015). Lors d'une conversation plus tardive, tenue en 2017 au Getty Center de Los Angeles, il précise : “In Flagrante means ‘caught in the act,’ and that’s what my pictures are. You can see me in the shadow, but I’m trying to undermine your confidence in what you’re seeing, to remind people that photographs are a construction, a fabrication. They were made by somebody. They are not to be trusted. It’s as simple as that.”

This text is translated by Anja Grøner Krogstad.

VIBEKE TANDBERG

Vibeke Tandberg, Old Man Going Up and Down a Staircase, 2003.

Afterimage by Jocelyn Allen:

I’m currently pregnant, and I’ve never been before, so it’s a big change for me and my body. I have photographed myself for over 10 years and at the moment I am working on a series about my pregnancy. As a result, I have been looking to see how other women have photographed themselves during this time, as well as post-birth, and early motherhood.

A series that sticks out in my mind is Vibeke Tandberg’s Old Man Going Up and Down a Staircase (2003). In the work she is pregnant and dressed as an old man with a mask on. I imagine she did this to playfully talk about the restrictions and difficulties that pregnancy can present. Tasks that were once simple like walking up and down the stairs become more difficult, but with pregnancy it is often only a temporary change. I like this series as it is quite different to other work that I have seen. It is playful whilst commenting about something very relatable that might ring true to you even if you have never been pregnant, but experienced something else like having a broken bone or feeling rough after a night out.

Tandberg’s work makes me think about my grandmother when I visit her house. She wants to do things for me as I am pregnant, but it is difficult for her because of the changes to her body now that she is older. She says she will make me breakfast, but instead I make her breakfast as I know it is much easier for me to do it. She gets frustrated whilst going shopping and everyone opens doors for her as it makes her feel like she looks old, whilst I get irritated by people meaning well but telling me to eat and rest well, like I have forgotten the basic needs of being human.

I am currently about halfway in my pregnancy and my movements are becoming more restricted. Picking something up off the floor requires some repositioning and my days of putting my socks on whilst balanced on one foot will soon be paused (this morning I did one, but gave in and sat on the bed for the other one). I know that even though my body will probably never be the same again, I will be able to do these simple things again. Whereas for my grandmother these changes are now permanent and her ability to do these things will only get worse.

ERIN SHIRREFF

Afterimage by Erin Shireff:

I was working at a desk sometime in the mid 2000s, back in Brooklyn after graduate school, endlessly scrolling through Gawker.com as I tried to avoid thinking about the vague direction of my life when this image rolled onto my desktop screen, no accompanying text, carrying the header “Ghost in the Machine.”

It was a typical Gawker post — New York-centric, slightly caustic — and it hit me in the way it was likely intended. I probably laughed. But the picture itself, a low-fi cell phone snap taken quickly (maybe on a Blackberry?), it stayed with me and provoked something less formed, more ambient in my mind.

After a beat you get that this isn’t documentation of a performance, the person in the photo isn’t pulling a prank. It’s likely a picture of one of the many, many people living in New York who don’t have a home, who use the subway as a place to sleep or rest. Someone trying to get just a bit of privacy within a life that probably affords them very little. So it felt wrong, or problematic, to think of this being a “relatable gesture” but I did. And I do. Abstract the conditions of this life I can’t imagine through a degraded photo on a website and I remember how when I first moved to the city from the desert I felt physically damaged, daily, by the number of faces — eyes — I had to see each day. Most days I felt enormously, thrillingly anonymous but that feeling could tip when the wave of humanity became a sea of individual people. Eventually I acclimated or maybe I just numbed out. Maybe I was already part way there when I looked at this picture and laughed.

It makes me think, too, about how I fetishize privacy. I am alone in my studio most of the day and I’m not convinced it’s a super healthy way to live but it’s a condition I rely on in order to hear myself clearly. That’s old fashioned I guess? The idea of privacy or aloneness being required for thought? Or maybe the notion of privacy itself — keeping something entirely to yourself, that being enough, not telling anyone — is just over. Sometimes I think we care about privacy only when we’re asked if we do, or when we think it’s being taken away.

Gawker is dead now, Blackberries are done. The sensibility of the writer that would have made that post has probably shifted. My own self-indulgent post-grad anxieties about creative autonomy that probably drove my connection to the picture in the first place — they’ve thankfully faded. Back then I printed it out on my desktop Epson and it’s here on the wall in my studio now like it was in Brooklyn for so many years. I’m gone, too. I travel on a different subway in a smaller city where it feels much harder to disappear. The ghost hangs above my sink in a black metal frame I picked up at Michael’s, discolored by shitty inkjet banding and years of UV damage. I guess now it’s a souvenir? I wouldn’t say it haunts me, but it’s never quit working on me, never not made me uneasy.

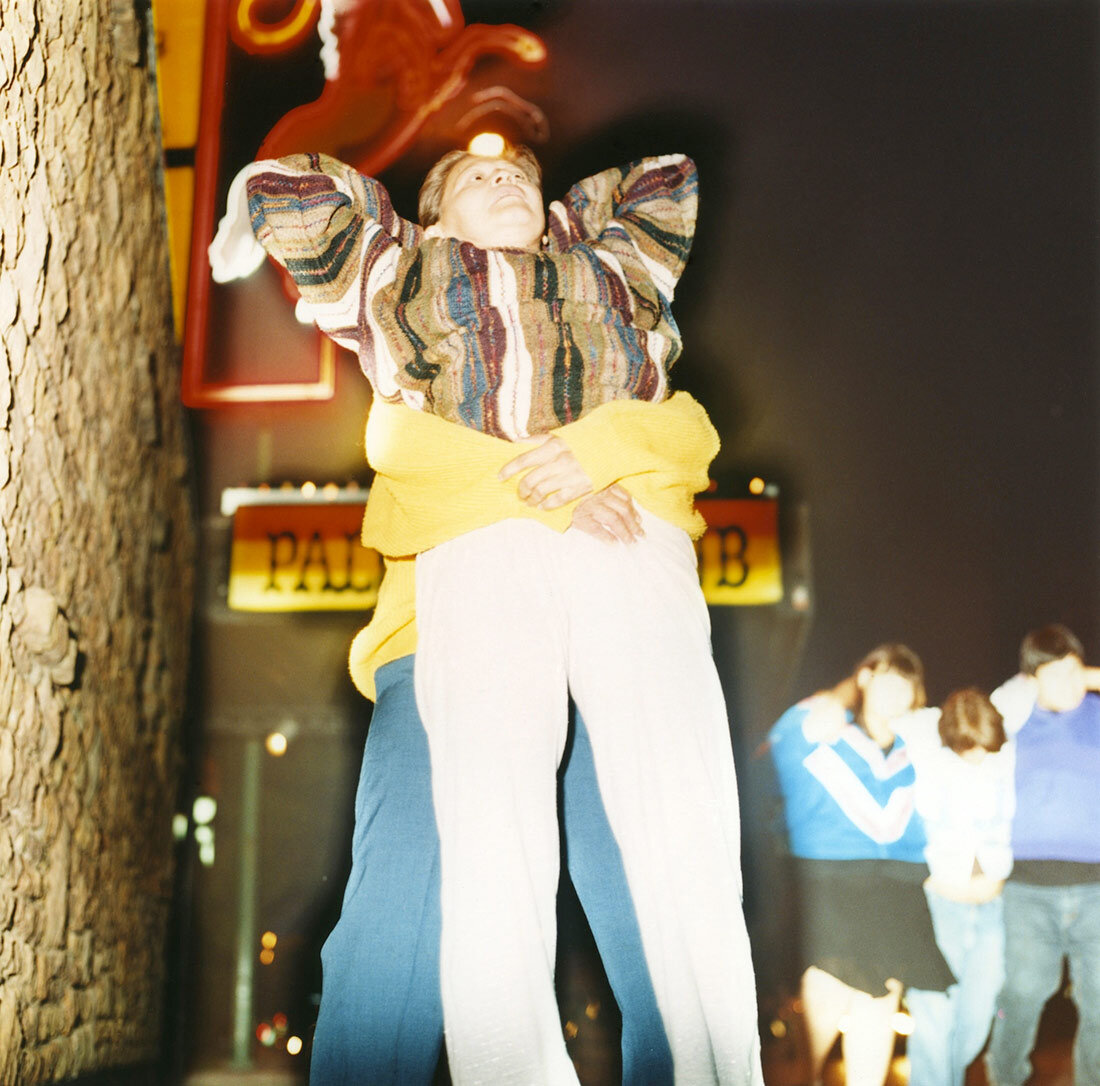

YORGOS LANTHIMOS

A still from Dogtooth by Yorgos Lanthimos, 2009.

Afterimage by Camille Lévêque:

I’ve always been strongly influenced by cinema. I’m rarely interested in photography, but often in videos made by artists. Film stills remain on my mind in a way that’s slightly different from photographs.

Since the first time I watched it in March or April, I've kept a screenshot on my phone from the film Dogtooth (2009) by Yorgos Lanthimos, who represents the new wave in Greek cinema. He also made The Lobster (2015) and The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017). His films are very visual, and he has what I would call the eye of a photographer. They’re also extremely dark, and Dogtooth leaves you feeling anguished, but it hides its darkness behind a lighter appearance and colourful scenes. The movie as a whole is beautiful, but each individual scene is well orchestrated: if you paused at any moment, you’d have a really interesting still image.

Dogtooth is about an isolated family. The parents keep their kids completely outside the world by creating a fantasy to keep them at home. I have one scene in particular on my mind – the one that I saved on my phone. It depicts a birthday. We don't know whose birthday it is, but of course, only the family is present. At one point, the daughters perform a dance to their brother’s guitar, and it’s terrifyingly awkward. The scene arrives near the end of the film, and a lot of tension has been building. It reaches a point of almost unbearable uneasiness and you know something terrible is bound to happen, and yet it only becomes increasingly absurd.

I’ve grown up with an education in cinema and watched all the classics, so many films made these days don't interest me at all. I’m interested in an experience rather than entertainment. My expectations when it comes to cinema are ridiculously high. When I see a movie, I want it to change my way of thinking, and almost change my life, and Dogtooth does this, in a way. I regularly look at that scene on my phone. I really love the grotesqueness, absurdity and darkness in the film. But it’s hard to watch – almost like witnessing an accident and being unable to look away.

ELAINE STOCKI

Elaine Stocki, Palomino

Afterimage by Curran Hatleberg:

Even though it’s been years since I first saw her work, many of Elaine Stocki’s photographs have stuck with me and claimed importance in my mind. This is probably because they evoke such a unique intensity of mood and feeling. They are haunting, and they just don’t look like any other photographs I see. Palomino is no exception. It is a wild, swirling chaos of color and gesture that gives off a burning heat. It almost scares me. Somehow Stocki figured out how to summon the dream state, or enter into a hallucination where the normal rules of reality don’t apply. I have no idea how she does it. One of the many joys of this picture for me is surrendering to its mystifying trance, letting its force pull you in.

Another part of the magic of Palomino – aside from the distinctive mood and feeling – is that it rejects easy interpretation. It’s impossible to pin down. It suggests clues as to what might be happening but reveals nothing. Even after studying the photograph for a long time there are no definitive answers. It’s a moment that is powerful precisely because of its lack of clarity. To me, it’s this open-ended quality that makes this image so amazing. Stocki invites the viewer to participate in their own creative interpretation and invention, allowing them to trust their imagination and let go. Palomino, like all my favorite artworks, is experienced more than understood.

A while back I read something the poet Mark Strand said in an interview that I saved in my phone. I keep returning to it now and then. Looking at Palomino, it seems appropriate here: “…we live with mystery, but we don’t like the feeling. I think we should get used to it. We feel we have to know what things mean, to be on top of this and that. I don’t think it’s human, you know, to be that competent at life.”

PATRICK KEILLER

Patrick Keiller, a still from LONDON, 1hr 40 min, 1994.

Afterimage by Helene Sommer:

I stumbled across the work of Patrick Keiller over 10 years ago, as I was scavenging the web for one thing or another. It was a clip from Keiller’s film London from 1994 and it immediately resonated with me on numerous levels. The first image is a shot of the iconic Tower Bridge in London. It’s a dreary and grey image. Quite unspectacular for a motif usually belonging to postcards and mugs. In general most shots in this film are seemingly both mundane and laconic, depicting ‘ordinary’ though very precise observations from everyday life in a city. There is no camera movement, only a static camera. No actors, no scenography. The bridge opens and a cruise ship slowly sails through.

In stark contrast to the imagery is the voice-over and soundtrack. The nameless narrator, who arrived on the cruise ship where he worked as a photographer, is meeting up with his ex-lover Robinson after 7 years. We never see either. The film is a wonderful mix of fiction and documentary. The soundtrack, in addition to the voice-over, has multiple references to the dramaturgical use of film music that contrasts the imagery. The narrative is complex and sometimes surreal in its multiple idiosyncratic references and juxtapositions - simultaneously very funny and deeply serious.

Together with the nameless narrator, the eccentric and visionary Robinson sets out to understand the ‘problem’ of London through a melancholic survey of the ruins of an urban ideal. A kind of psychogeographical travelogue investigating the multiple layers and textures of the city. Robinson solemnly drifts around London and reflects upon the historical undercurrents of the city’s many streets and buildings. He traces views that once inspired great painters, ponders Baudelaire while drifting through a Tesco supermarket, notes that in Lambeth there is a fence made out of beds from air-raid shelters, plans for a contemporary postcard series with the city’s homeless, tracks down flats of famous poets and traces the aftermath of an IRA bombing and the economic crisis in a post-Thatcher landscape.

Since watching London for the first time, I have seen most of what Patrick Keiller has produced; films, books and exhibitions. And I keep coming back for more. It’s the type of rare relationship that never gets old. London (1994) is the first part of a trilogy which includes Robinson in Space (1997) and Robinson in Ruins (2010), all highly recommended.

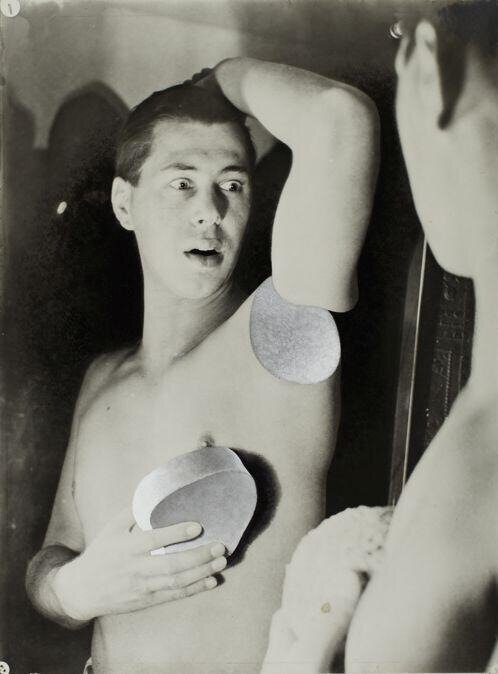

PHILIPPE HALSMAN

Philippe Halsman, French poet, artist and filmmaker Jean Cocteau. NYC, USA. 1949. © DACS / Comité Cocteau, Paris 2018. © Philippe Halsman | Magnum Photos

Afterimage by Alix Marie:

Perhaps because it was summer when I was asked by Objektiv to write about an image my choice has been influenced by the past. I was in France and had spent a lot of time sorting through hundreds of family photographs; postc Marieards and memorabilia from various periods of my life. The two images that came to mind were Herbert Bayer, Humanly Impossible (Self-Portrait) from 1932 and Philippe Halsman’s photo of the French poet, artist and filmmaker Jean Cocteau from 1949. Bayer’s self portrait is an image I discovered as a teenager at the Bauhaus Museum on a school trip to Berlin. It has been in each of my bedrooms, in the form of a postcard or poster ever since. But then I felt that talking about it might actually kill the mystery of its power over me, so I’ll talk about Cocteau.

Herbert Bayer, Humanly Impossible (Self-Portrait), 1932.

Halsman’s portrait returned to me as he has always been one of my heroes. Still today, as I am preparing my next show at Musée Des Beaux Arts Le Locle, I find images from La Belle et la Bête popping up in my head constantly. My family comes from cinema, and films are more influential in my practice than anything else, perhaps even more specifically the favourite ones from my childhood. Cinema is historically and socially a big part of French culture, Paris being the only city in the world where you have one cinema screen per hundred inhabitants. The average of going to the cinema is twice a month, it is very much part of our habits, and it’s something I miss here in the UK.

I remember as a child looking for through an encyclopaedia on cinema and for Cocteau they just wrote: génie à multiples facettes. I thought that was the most wonderful definition of an artist. This is exactly what the portrait depicts: Cocteau’s ability to write (poetry, plays, screenplays), set design, draw, paint and direct films. In a sense I think we can also read this portrait of an artist in a contemporary sense, as artists we are asked to have an incredible amounts of skills in order to survive: make good work, know how to write about it, know how to speak about it publicly, do your own PR through social media, know how to sell your work, teach...

Thinking of my practice which often mixes mythology and autobiography, and my passion for mythological antique sculptures, I think perhaps it originally came from Cocteau. As when he turns Lee Miller into an armless goddess in Blood Of A Poet for example. The transformation, if I remember correctly, was achieved by covering her in flour and plaster which must have been extremely uncomfortable. It is another aspect of Cocteau’s films which fascinates me: his DIY special effects which in themselves carry so much poetry. I think for example of when Jean Marais walks through the mirror in Orpheus for example, it is just cut and paste, instead of a mirror it is water when he goes through. This is something I try and keep in my practice; it comes from the everyday and the ordinary as I try to make and fabricate everything I can myself and often repurpose domestic objects. The manipulations in my work are physical, I never manipulate an image digitally. In the end these two images share a lot in common, they use analogue tricks to achieve a poetic and political portrait or self portrait of the artist, and they carry a reference to antique sculpture, all aspects which have fed my practice since very early on.

ROBERT FRANK

Robert Frank. Words, Mabou, 1977. Vintage gelatin-silver print. 31,2 x 46,8 cm. Collection Fotostiftung Schweiz, Gift from the artist.

Afterimage by David Campany:

When people look at my pictures, I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read the line of a poem twice.

In 1954-56, Robert Frank was on the road in the USA, making the photographs for what would become The Americans, perhaps the single most influential book by a photographer. Swiss by birth, Frank came to America in 1947. Politicians and the mainstream media were full of post-war optimism fueled by consumerism, television and Hollywood. All Frank could see was disappointment, alienation, and systemic racism. Published first in France in 1958, the images were accompanied by an anthology of quotes from various writers about the country. When the book appeared in America the following year, the quotes had been replaced by a foreword by Frank’s friend Jack Kerouac. The publisher was Grove Press, the primary outlet for the Beat generation poets.

Frank’s images were willfully subjective. They were also highly sophisticated redefinitions of the nation’s iconography. The stars and stripes flag recurs, but it is tattered or obliterating the faces of citizens. Movie stars look uneasy. Manual workers feel dejected. Passengers on a trolleybus arrange themselves by race. Motels and gas stations are bleak and forgotten. But through the metaphor and allegory there was also a romantic and angry longing for something better.

Modern America is a restart, an experiment. Its keenest observers in photography, film, painting, literature, theatre, and poetry have been monitors of that experiment. The Americans divided opinion but its reputation, particularly among other photographers, grew rapidly. For some, Frank had opened a rich new vein of image making. For others, his achievement could not be surpassed and new directions would have to be taken. Frank himself left photography almost immediately after The Americans, and took up filmmaking. In 1971, he moved from New York to Mabou, in remote Nova Scotia, Canada. He returned to still photography but not in pursuit of singular, iconic images. He made collages, mixing photographs and writing in different ways. As he pushed onwards, he looked back from time to time. The Americanswas becoming something of a counter-cultural monument. Museums and collectors were beginning to acquire prints. Frank grew reluctant to talk about The Americans, feeling that all he wanted to say had been said, and was in the pictures anyway. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, the book has become the most discussed and analyzed of all photographic projects, the subject of endless essays and assessments.

In this photograph we see prints hanging on a washing line, on the coast of Mabou. There is an image of people on a boat. Frank shot it on the SS Mauretania, the day before he arrived in the USA. There is a photograph taken at a political rally in Chicago, 1956. It is one of the best-known images from The Americans. On the right, the word ‘Words’. Perhaps it was Frank’s sign of exhaustion with the endless talk about his work. Perhaps it was a substitute for an image, a placeholder for a language to come. Words have accompanied and haunted photographs from the beginning, and ours is a thoroughly a scripto-visual culture. Images conjure up words, and words conjure up images. Both are substitutes for realities they can never quite express, even with each other’s help. They are apart yet connected, like transatlantic friends.

The text is from Campany’s forthcoming book ‘On Photographs’, Thames & Hudson, with a few changes for our series.

LEA STUEDAHL

Afterimage by Lea Stuedahl:

A while back, my grandfather gave me all his negatives, pictures he had taken from when he was a teenager until he became a father. Through at these images I got to know him as more than my grandfather - whom I already love and admire. I got to know parts of him that has always been there, the core of his personality. In some ways it makes me understand him in a way that wouldn’t be possible otherwise. This is something I find compelling with photography; the way we might try to understand the photographer at the same time as we try to understand the photograph. There is so much identity attached to it. What we photograph says something about us as a person and how we see things. Looking at it that way, it is a really raw and vulnerable form of talking. So quiet, but yet brimming with words.

For me, this is the perfect picture for a daydreamer. I’m immediately taken away; the wind is playing with my hair, I can feel it. I want to be there, looking at this view. I long for the mountains and the smell of vacation in the south of Europe. I want this to be my own memory, and to always remember having seen this. The picture is taken by my grandfather, on his honeymoon with my grandmother. Their relationship didn’t last and I never got to experience the love they once shared. It’s a memory that’s not mine, from a time when I wasn’t. An everyday situation I’ll never know, and can only imagine. That’s the thing with photographs; it will never be one’s own reality, only a perception set in motion.

LINN SCHRÖDER

Linn Schröder, Selfportrait with twins and one breast, 2012 . (In cooperation with Elke Rüss).

Afterimage by Clara Bahlsen:

This image has been with me for a long time, it’s so special to me. I know the photographer, we have talked about photography, but we have never talked about this image.

I really relate to Linn Schröder’s picture, maybe everyone does, this borderline situation of life and death, how it talks about fear. It is such a poetic and dramatic image at the same time, and it’s bigger than words.

I feel that I can be part of the picture, it is kind of a community thing for me. Will one breast be enough? We see this male figure in front of the kid where there is no breast, and I feel it could be my hand. That I should take part in raising these children and maybe take care of the mother as well. You don’t see her face, it’s all about the bodies. It could be my body, or your body, we could all be in this situation. I can adapt to this very moment, which is strange as it is such a special and private one. To me the picture is not about one specific mother surviving an illness - it is us, all of us human beings, taking care of each other, sharing love and fear and life and death.

Maybe, since I have a child myself, this image became even more important to me. Death is closer now, my time will end before my son’s time. Since he came to this planet thoughts like these are more present to me, I can feel time running through me. I see this in the picture, they can’t die today, they have to get through this. You only see the faces of the children, no father, no mother, only the future. They depend on adults right now, but they will be fine later.

Some images become part of my own biography. I feel that I have been there, but of course I haven’t. But still, I’m unable to erase them from my mind. Unable to ever forget. They even physically become part of my body as the pictures are stored in my brain. That is such a powerful act.

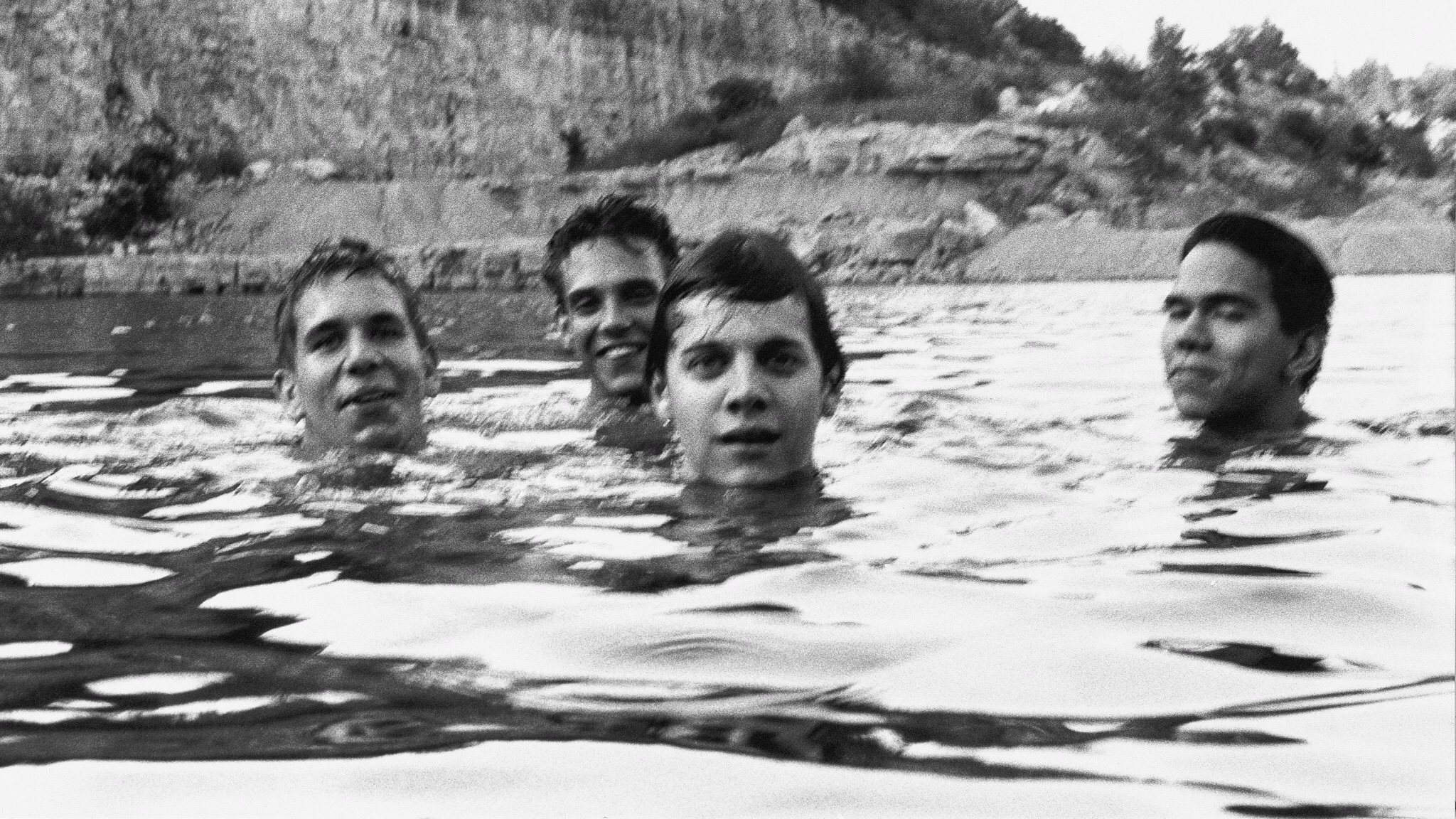

WILL OLDHAM

Spiderland cover photo, Will Oldham.

Afterimage by Marius Eriksen:

The image on the front cover of Slint’s seminal album Spiderland, taken by Will Oldham, the musician behind the various monikers Palace Music, Palace Brothers and Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, is an image that entered my life at sixteen. Browsing through CD’s in a record store, the image of four heads bobbing in a quarry gave me a strange mix of contradictory feelings, feelings of emptiness and warmth. The photograph seemed so familiar, like I had experienced that exact moment myself. It felt like I was standing in an alternate universe looking at a moment that I had been part of in some strange way. I’ve tried several times to recreate this image in the many creeks and rivers of my hometown without any success. I never managed to create the same type of eerie feeling. I guess some moments just aren’t easily reproduced, or maybe some moments aren’t meant to be reproduced.

Looking at the four persons half submerged in the water with their faces half-smiling, it felt like they were staring right through me, like there was some dark Lovecraftian force lurking in front of them and that it was hanging over me. Could their gaze be an omen? An omen that my salad days were drawing to a close? That the future was going to be lined with darkness and destitution? I had no idea what to make of it, but my mind was racing just looking at that cover. It felt like it took some time before my mind managed climb out of the existential void this image hurled me into and my focus started to shift. Looking at that image again, their gaze wasn’t longer an unsettling gaze, it offered consolation. Their smirking faces provided a sort of stoic consolation, a promise that no matter what lies ahead, the bottom line would be that things would nonetheless turn out to be OK.