MAX DUPAIN

Whenever the word photography comes up, this image always comes straight to my mind. When I was introduced to the art of photography, around the age of 13, I was captivated by Max Dupain and the influential nature of his career – particularly his pioneering influence of modernism to Australia.

One Image by Julia Clark:

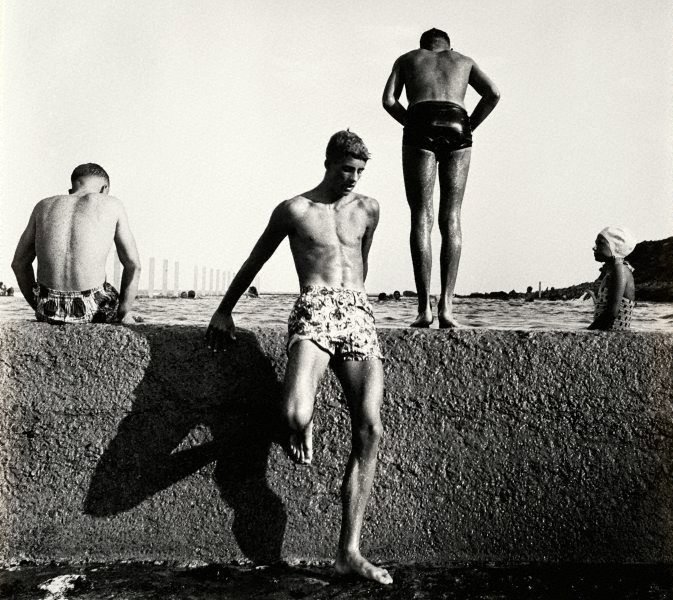

Whenever the word photography comes up, this image always comes straight to my mind. When I was introduced to the art of photography, around the age of 13, I was captivated by Max Dupain and the influential nature of his career – particularly his pioneering influence of modernism to Australia. For me, this image At Newport will forever be engraved in my mind. The composition, the leading lines, the shadows and the illusion of it being cut in half, are all so engaging and aesthetically complex that I find myself thinking about it all the time. All the subjects seem so perfectly propped that anyone would be forgiven for assuming it was staged, and the fact that it’s completely candid just speaks volumes about the skilled and watchful eye of Dupain.

One of the shapes that captures my gaze in this image is the shadow of the man standing in the middle. Despite his position being central in the frame, his shadow is as engaging to the eye, and even more so, it manages to compete with all the subjects as the most eye-catching aspect of the photograph. Aside from the shadow, this image has influenced me in so many ways, most notably the varied layers and textures in the image, the shapes and their interplay, and the objectification of the human subjects – making them shapes rather than people – their organic forms make the viewers eyes bounce from subject to subject making the image circular, causing the eye to view the image as a whole.

This image is even more interesting due to its positioning of a subtle undertow of social discomfort in an otherwise idyllic scene. There is something slightly unsettling about the disjointedness of the bathers, the hunched over, spine exposing stance of the man furthest to the left, the positioning of the man in the middle – looking as though he is bracing to hold back the weight of the ocean on the other side of the wall. Beach scenes, in Australian photography, are iconic for their imagery of the ideal summertime, but Dupain, in At Newport, very subtly challenges this norm, capturing both the glee of post war Australia, and the uncertainty of what was to come.