EM ROONEY

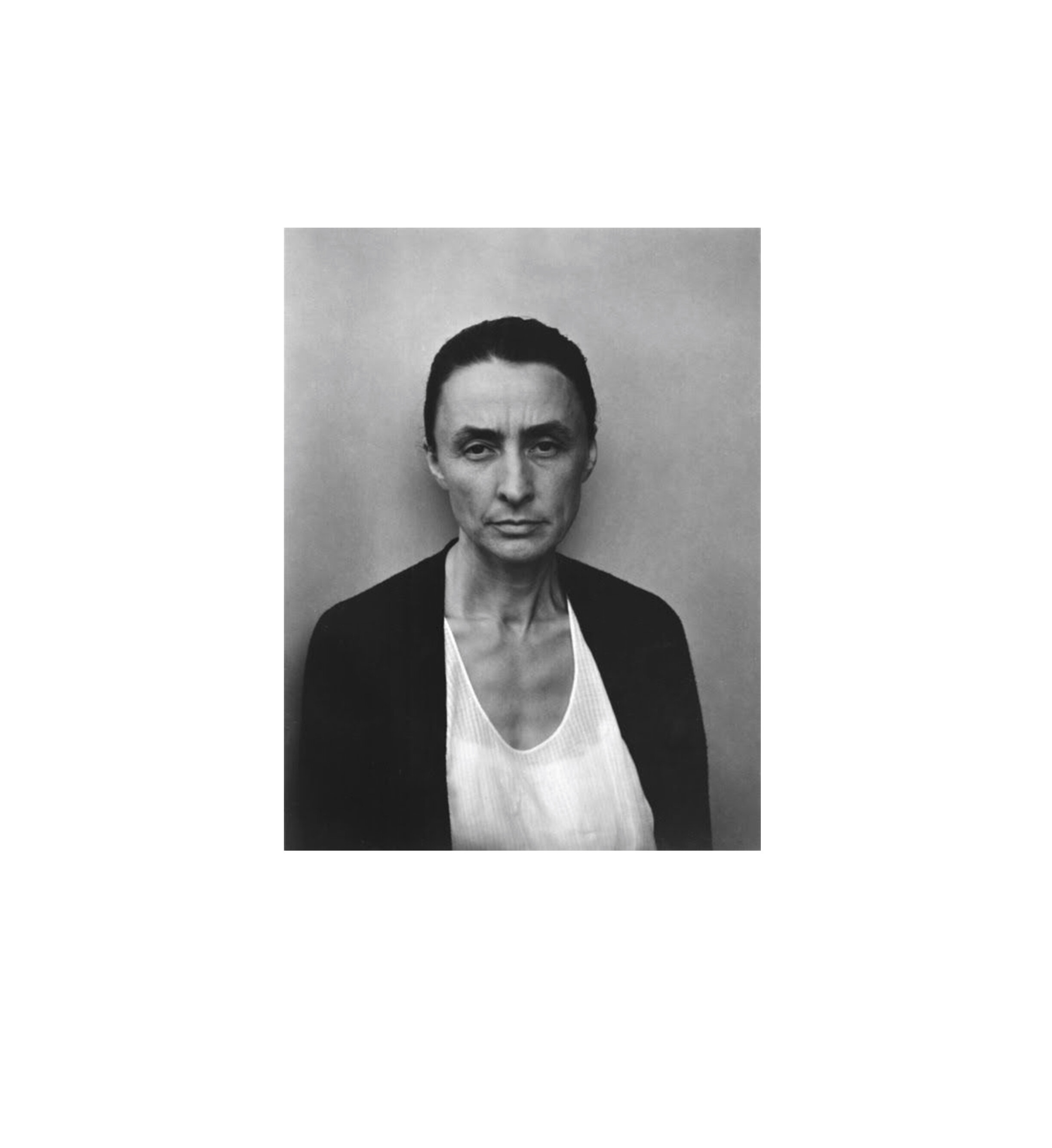

Alfred Stieglitz, photo of Georgia O’Keefe, source unknown.

For this twentieth issue, in the tenth year of the magazine, we’ve invited twenty artists to contribute. Some have been given carte blanche to create unique portfolios or collage-like mind maps about the kind of photography that inspires their practices—and perhaps, through this, share something about their future paths. All the artists to whom we gave carte blanche to make work for this issue, were given five inspirational questions on which to reflect. Short statements accompany each artist’s contribution. Em Rooney is showing the work of other artists, in this case work by Alfred Stieglitz. The photographs appear to have been shoved into the pages of a book and this is closely related to Rooney's own way of working.

Looking back on your work to date, what patterns or consistent inquiries can you see that you couldn’t predict when you started? In college I was having the explosive experiences of first love and of learning about my body. And, of course, these things were totally incongruous with religion and family – and there a triangle was formed that occupied me conceptually throughout my college years. I would say that I couldn’t have predicted that I would still be interested in Catholic structures and narratives, or even the architecture of the church, but that would be to say that I knew I ever had been, or that when I started making work seriously that I could have predicted that I would have been an artist, or that I knew what being an artist was. Bewildered, sometimes I can’t believe I am actually an artist, and maybe that’s the thing that would have been the hardest to predict.

The way that I’ve often thought about photographs as private, personal, and small (and this is something I’ve already spoken a lot about especially in relationship to the pieces at MoMA) I think might have its roots in the way photographs were often stored at my house when I was growing up. They weren’t typically on display. They were in hidden in boxes in the attic, or shoved in the pages of books– old family photos, or pictures of my mother in High School might drop out of the OED or the Joy of Sex when you pulled them off the shelf. So that relationship between the page, and image (and its one that Sontag, Barthes, Berger, Davey, bell hooks and many others have often spoken about) was there for me when I was a child, and has reoccurred formally, on and off, throughout the past ten years.

Alfred Stieglitz, photo of Georgia O’Keefe, source unknown.

This time has been stuffed to the gills with non-stop reading about, teaching about and seeing shows; talking about work (with my long-time love, artist and collaborator Chris Domenick) first thing in the morning, last before bed at night; getting into serious fights with friends about work they like/don’t like and why; writing about work I love and curating shows, and pouring myself into it. This question, of what has resonated with me, would be incomplete unless it were to include the work of all my friends and everything I learned from Chris and his practice, and every show I’ve seen and then verbally dissected (not to mention the work of so many gifted students I’ve taught since 2010) – the number is probably in the thousands. Below are five. Not the best, not the most important, probably the lowest-hanging fruit, they’re first five that come to mind which might actually say a lot.

The first show I remember seeing in a Chelsea Gallery with Chris was a Richard Artschwagger show. It was these TV-fuzz looking ‘paintings’ and Formica sculptures that didn’t really mean anything to me at the time, but I always remembered them, and in the years that followed I’m sure I saw every show Artschwagger had in New York. I specifically remember a show of his I saw in 2012 at David Noland called The Desert. It was these beautiful, small pastel drawings on coloured paper, of landscapes. And there’s certainly a way that these drawings influenced my first solo show at Bodega, four years later.

There was also Leidy Churchman’s 2015 show at Murray Guy, The Meal of the Lion, which impacted my thinking about the way a group of disparate images could be held together with an artist’s touch and intentionality.

Arthur Jafa’s film Love is the Message the Message is Death at the Met Breuer reminded me that there’s a directness, something like rhetoric, that images have, that’s extremely powerful. And that withholding is learned and not not a default modus operandi.

Inversely, Trisha Donnelly’s 2010 show at Casey Caplan was charged with mystery, and taught me that sculptures can function like images in that they hold inescapable material realities.

Catherine Opie’s show earlier this year at Lehmann Maupin, comes to mind. It featured the artist Pig Pen as protagonist in a fictional, doomsday narrative laid out in a series of photographs and a film. Pen Pen (aka Stosh Fila) is a person I love looking at who Opie has been photographing for years. The magic of the photograph can be very simple, just like that; I like looking at you. And this is a watered down version of punctum I guess. But I love thinking about who or what a photographer photographs over time. What subject does she return to? As a student I was obsessed with Steiglitz’s photographs of Georgia O'Keeffe, how we could watch her age (becoming more handsome with every year). We saw what Steiglitz saw (although O’Keefe lived much longer after he died). What privilege the photographer grants the viewer, a stranger to the world of her intimacy. Opie’s show felt particularly impactful as I realized her subject, had become someone I’d grown up with as well.

Alfred Stieglitz, photo of Georgia O’Keefe, source unknown.

Because of my closeness to dancers and choreographers (Strauss Bourque-LaFrance, Lydia Adler-Okrent, Marianna Valencia) I’ve thought a lot about dance. My first ‘real’ show was a two-person exhibition with Strauss Bourque-LeFrance at Bodega’s first gallery space in Philadelphia in 2010. There was this whole element of dance that Strauss brought to the show through a slide projector that clicked through stills from a performance he’d made. But there was also the idea that the work could be activated by movement, that everything was somehow a prop with latent or expired use. We were talking then about ‘queer formalism’, which I think nine years later sounds passé but the point is that we were sure our queerness was clear in our invitation to the viewer.

I think the pictorial turn might be the last turn, especially if we think of it in relationship to Foucault’s ideas about surveillance. I’ve seen corporate tools and machines that render quality/detail/data more quickly and easily, tools that are more often, historically and presently, used for military and capital gain; drones and advanced data processing systems, and facial recognition software, used well by responsible artists. But, I worry that the merging of scientific/corporate invention and genuine creativity will continue to alienate us from our physical world, biochemical feelings, observations and instincts and this will hasten the destruction of the planet.

This is the full statement from Em Rooney from our current issue. The launch of Objektiv #20 is at Polycopies 07/11/19 from 12 to 8 pm. Bateau Concorde-Atlantique /Berges de Seine - Port de Solferino / 75007 Paris / Métro: Concorde or Assemblée Nationale.