TIAGO BOM

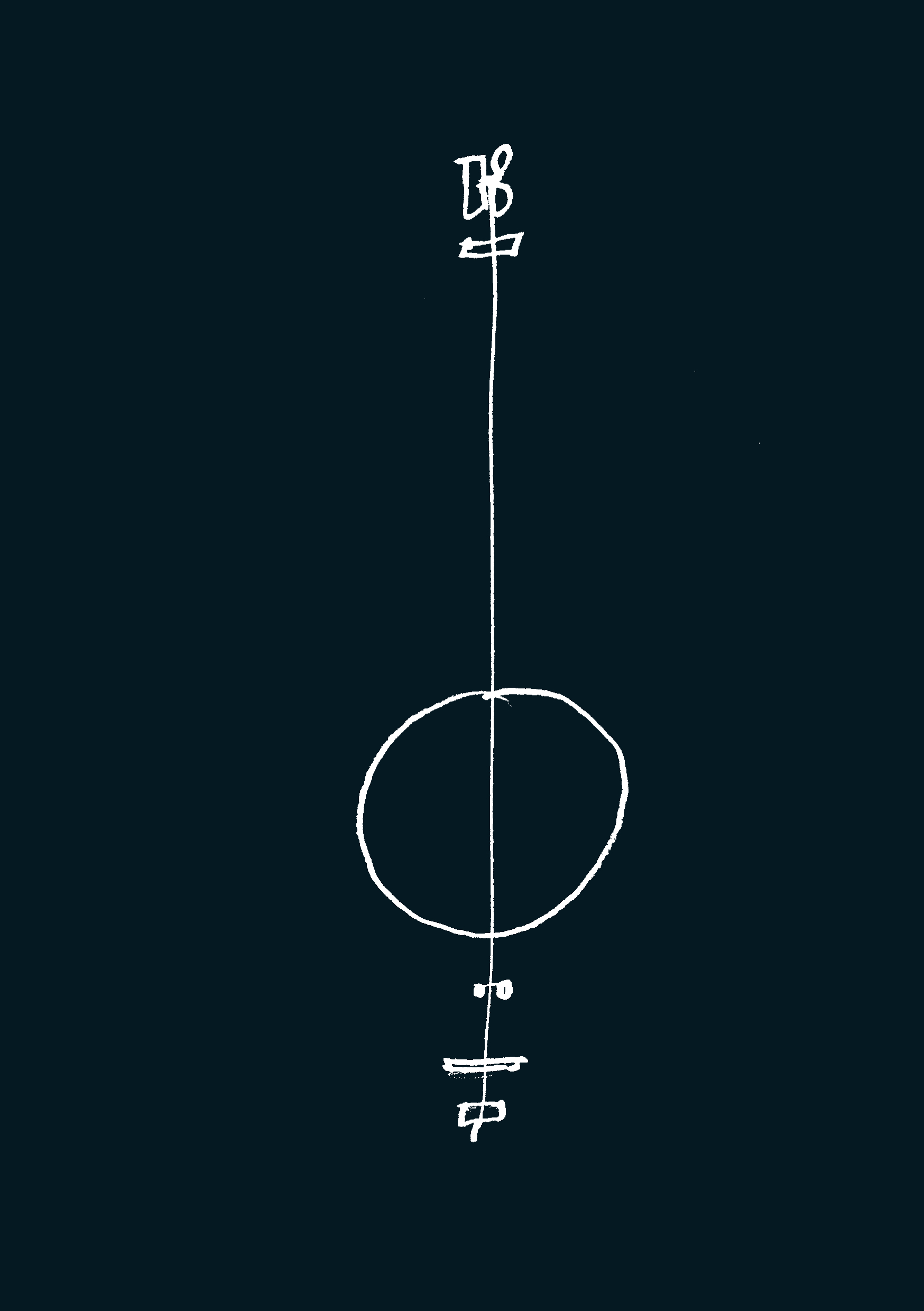

Rui Toscano, The Right Stuff, 2008-2009. Photo © DMF, Lisboa.

This year’s issues investigate, from both institutional and artistic perspectives, the practice of exhibiting camera-based art. For the autumn issue we’ve asked several writers, artists and curators to reflect on the memorable displays – whether in galleries, books, magazines, online or on billboards – that have remained in their minds. Here is Tiago Bom’s contribution:

Action, with all its uncertainties, is like an ever-present reminder that men, though they must die, are not born in order to die but in order to begin something new. Hannah Arendt in Labour, Work, Action.

What does it mean to ask if an art exhibition worked or not? Even though it may seem like an irrelevant exercise, it may prove to be profound. The clue to this profundity might lay within language itself, in particular the word work. Work as a concept is implicitly related to the act of transferring energy from one place to another, from a form to another. This act of transferal can be both mental and physical and is in itself an act of transformation. In turn, these acts of transformation play a ubiquitous role in our individual existences as by-products of our social circumstances. This exchange is often translated as effort for money, money for time, time for effort – transformation through effort; creation, if you will. Taking work to mean transformation and creation is a convenient way to start analysing any art experience including an exhibition. In her essay Labour, Work, Action, Hannah Arendt touches upon the philosophical and political ramifications of a myriad of pro-social actions and their entropic degrees. Arendt identifies all types of work as acts of creation in their own right, where the labour applied transforms them from being thought-things into a reality. She goes on by attributing them different levels of entropy, in relation to their utilitarian character or lack of it. Within this idea of work, “in the sphere of fabrication itself, there is only one kind of object to which the unending chain of means and ends does not apply, and this is the work of art, the most useless and, at the same time, the most durable thing human hands can produce. (...) Just as the purpose of a chair is actualised when it is sat upon, the inherent purpose of a work of art – whether the artist knows it or not, whether the purpose is achieved or not – is to attain permanence throughout the ages”.

Art works reverberate in each viewer differently and this difference in reverberation lies in the layered qualities of the work – this is perhaps what confers it its durability – and in the symbolic capital of each viewer. One other metric could thus be layers, the more layered the work or exhibition in this case, the more transformational potential it has. We can analyze these layers case by case, by establishing inter-causal relationships between all the social variables – tracing quasi-objective traits to a specific work – its historical links, its relevance and relationship with present production and, how well it embodies these – character traits that lie within the work and the way it chooses to show it self. In a social context, to affirm that an exhibition worked, is to essentially talk about legitimacy; collective legitimacy. An art exhibition is, after all, a meeting point of confluent social, cultural, economic, and political variables (socio-historical) juxtaposed with personal agency and labour. Within this context, art should serve as an autonomous space for the debate of the fundamental questions pertaining to our Ethos and it should, in all instances, conserve a relative autonomy to all these variables.

In sum, we have to look at the artwork as a thought-thing, another link in the chain of labour, but an exceptional one. Non-utilitarian in character and with implicit endurance to time, the art works in an exhibition should function as cohesive parts of a larger debate on our Ethos. Cohesion is only accomplished with a layered structure of content made by relating to its socio-historical variables and questions of representation, while remaining relatively autonomous to those variables.

The Great Curve in 2009, by Rui Toscano, is one of such examples. This exhibition took place at Chiado 8 in Lisbon, part of an outreach project developed by a Portuguese insurance company and, at the time in cooperation with the cultural branch of the largest state owned bank in the country (Culturgest). This cooperation, from 2006 to 2013, would end up fostering many exceptional exhibitions, always with a relative degree of autonomy, generated by a very unique set of premises.

Overseen by Miguel Wandschneider, head of program of Culturgest, this project aimed at showcasing four annual solo exhibitions by Portuguese artists to be selected by national curators who, in turn, would have a mandate of three years. The premises that made this initiative so special within the national scene at the time, were the fact that it didn’t have the usual pressure and constraints of the commercial circuit, nor the institutional demands of museums. The underlying idea was to exhibit national artists in all stages of their careers and with varied forms of expression and interests, while making use of the production resources allocated by those two institutions. Creating, this way, an overall unique opportunity for both curators and artists to step outside their comfort zone and develop a more experimental body of work. This freedom to take risks, combined with flexible time-frames, better logistics and production support matching institutional standards, was unparalleled at the time in Lisbon, according to Bruno Marchand, the curator for this exhibition. The result was a series of honest, relevant and well produced conversations between artist, curator and space, that materialized in transformative experiences.

The Great Curve put forth Toscano’s interest in sidereal space and presented a series of works that related as much to the concrete relations between celestial bodies – a field still largely unexplored – as it did to imagination (here seen as a sensorial mechanism that organizes and categorizes all that relates to our experience of art). As Marchand writes in his introductory text, “here we enter in the realm of the cosmos, in the domain of what is infinitely large and infinitely small, and where we start from an eminently speculative experience of the Universe in order to test its possible phenomenological translation”. I see The Great Curve having the same place of origin as science fiction – the cultural space between present technologic advancements and philosophic speculation. But unlike science fiction, this exhibition did not speculate on answers or possible future scenarios, instead it set forward a series of visual synthesis’ and observations, both on questions of representation but also socio-historic phenomena – consequence of a year long layered discussion between artist and curator.

Super Corda and Mother and Child, the center pieces, were in my opinion, the two artworks that had the most transformative power, bringing the proposal of the exhibition closer to its inception. Austere and elegantly arranged, these two works displayed an economy of means and, through their simplicity, an inherent conceptual complexity – allowing the ideas underneath to surface rather than being obfuscated by sensorial clutter. Super Corda consisted of an amplified contrabass string attached to a faux-wall. When played, this string would produce an eery bass sound amplified by a pickup, reverberating in the chamber created by one of the institution’s walls. The title of the work alluded to superstring theory in physics – the attempt to explain all natural behavior and fundamental laws, where particles are replaced by one-dimensional objects called strings that interact with each other in a vibrational state. Relating to light in a similar way, Mother and Child presented a superimposed set of two circular spotlight projections on the gallery wall. The scale and relationship between bodies were present here as a result of the difference in size of the two projections. The reflection of light, when in this pure form, forced us to establish a causal relationship between two repeated shapes and their hierarchical structure. While this question of scale in the representation of power is as old as the human pictorial production, in this case it was also a question of perception and perspective as much as representation. So is the use of light and the relationship between the spectrum of light reflected, refracted or absorbed. It is within this awareness, that we today – through the field of Spectroscopy (Astrophysics) – study the speed, temperature and material composition of astronomical bodies.

According to Marchand, “throughout the whole exhibition, there was an implicit game between the idea of observation and its limits/protocols but most importantly, the creative opportunities that arise from those limits”. In relative proximity, these two works amplified and resonated off each other. Whatever the image showed to hide, the sound revealed without showing.

Following the same criteria I would still highlight a second experience, Oslo based artist Per Platou’s exhibition, Platou’s Cave, at artist-run gallery No Place, in 2012. Much has been written about Norway’s financial support system for the arts – unmatched, to my knowledge, anywhere else in the globe – and almost always in relation to how it fostered a vast array of independent artist-run spaces, some more proliferous than others but always free of commercial constraints. No Place is one of those galleries that has achieved some legitimacy amongst the local art crowds. Almost every artist in Oslo has exhibited there at least once since they opened. They’ve exhibited established artists, artists in mid-career, young artists and art students. Their apparent lack of criteria in the choice of media and people is both their weakness and their biggest strength and, probably the reason why they are still up and running today, when many have closed their doors. No Place has a refreshing atmosphere contrasting with a milieu obsessed with numbers and names, an important characteristic to help contextualising this experience in terms of its relative autonomy in the field and matching lack of resources and economy of means. Platou’s Cave borrowed the name from the famous cave allegory presented in the manuscript of The Republic. This jovial word game, set the scene for a far more serious and profound experience. The mise en scène was separated by curtains of thick fabric, where a carpeted floor composed of laid out persian-style carpets and cushions against the walls advertently invited people to sit or lay down. The lights were dimmed to creating a warm and private atmosphere. Platou’s Cave was drawn from the artist’s experience as a sound producer for theatre and it worked essentially as a sound chamber, where random pre-recorded and found sound-bits were assembled in a looped montage. This would then be fed with amplified sounds from the exterior of the gallery, provided by a microphone apparatus on the outside. According to the gallery “Platou’s installations override any relegation of sound to a secondary animating layer, parting with the subservience of sound to dramatic action and other hierarchical fixtures of the theatre. To the extent that he employs objects or dramatic elements other than sound in the environments he constructs, their function is that of vicarious spatial proxies, addressed to and directing the movement and visual attention of the audience. Aesthetic primacy is preserved for the auditive.” The endless combinations and the potential arrangements of sound were gripping. In this somewhat familiar and womb-like environment, being surprised by these “shadows” of sound generated a whole new dimension for imagination to wonder and thrive.

Both examples share not only a personal transformative influence but are also by artists connected to the production of sound and music. Both do not shy away from this connection but do in fact often use it to mix and elevate their visual production. The ease with which a message travels through sound, activating a memory or a feeling, is prodigious. These two exhibitions generated a subtle movement from Dionysian to Apollonian ideals and vice-versa. Through sound and vision we were engulfed in an all-inclusive experience while being forced to exercise some critical distance.