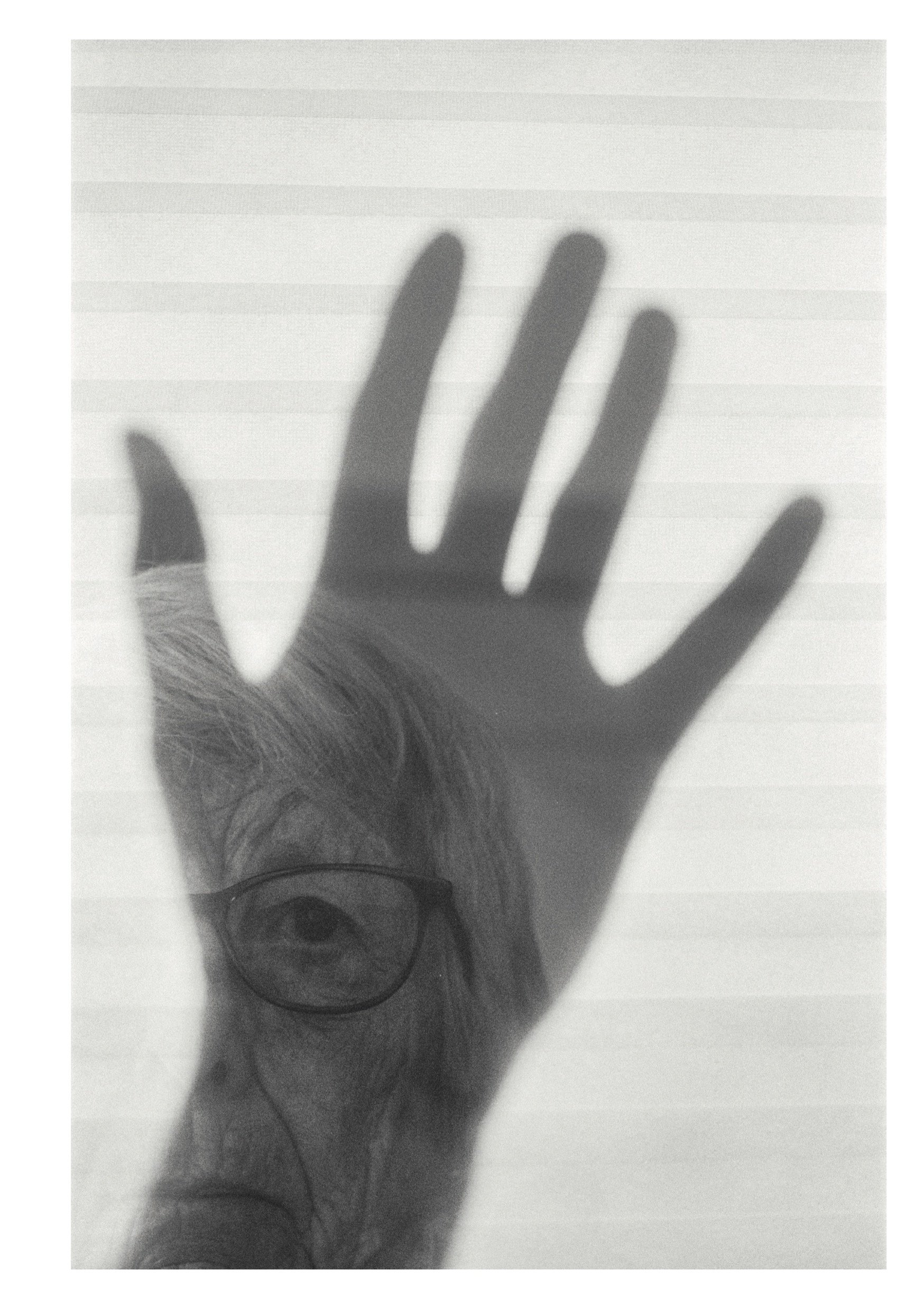

My autoportrait project has run over 40 years. The aim is to demonstrate the different ways in which you can have your portrait done in a studio or public space, as well as the different techniques photographers employ. The only reason I use myself as the subject is because I’m the one person who’s consistently there. Hanoi Studio took five black and white shots of me in different poses, and in one they gave me naff sunglasses. They then did a montage, printed in black and white, and hand-coloured.

When we were developing my show Diablo at MoMA PS1, the curators were interested in doing something that evoked the feeling of being in my studio. The collage Diablo was originally not meant to be an artwork, but was my answer to the question 'What does your studio look like?'

Diablo is a version of one of my foundational impulses: I have always made this kind of image collection, even as a kid.

I have been thinking a lot lately about the relation between ‘theory’ and ‘writing’, and ‘literature’. Many theorists don’t think of themselves as writers, and of course many writers don’t think of themselves as theorists. As we know, a lot of ‘theory’ is not very well written, probably because those who write it do not think of themselves as writers.

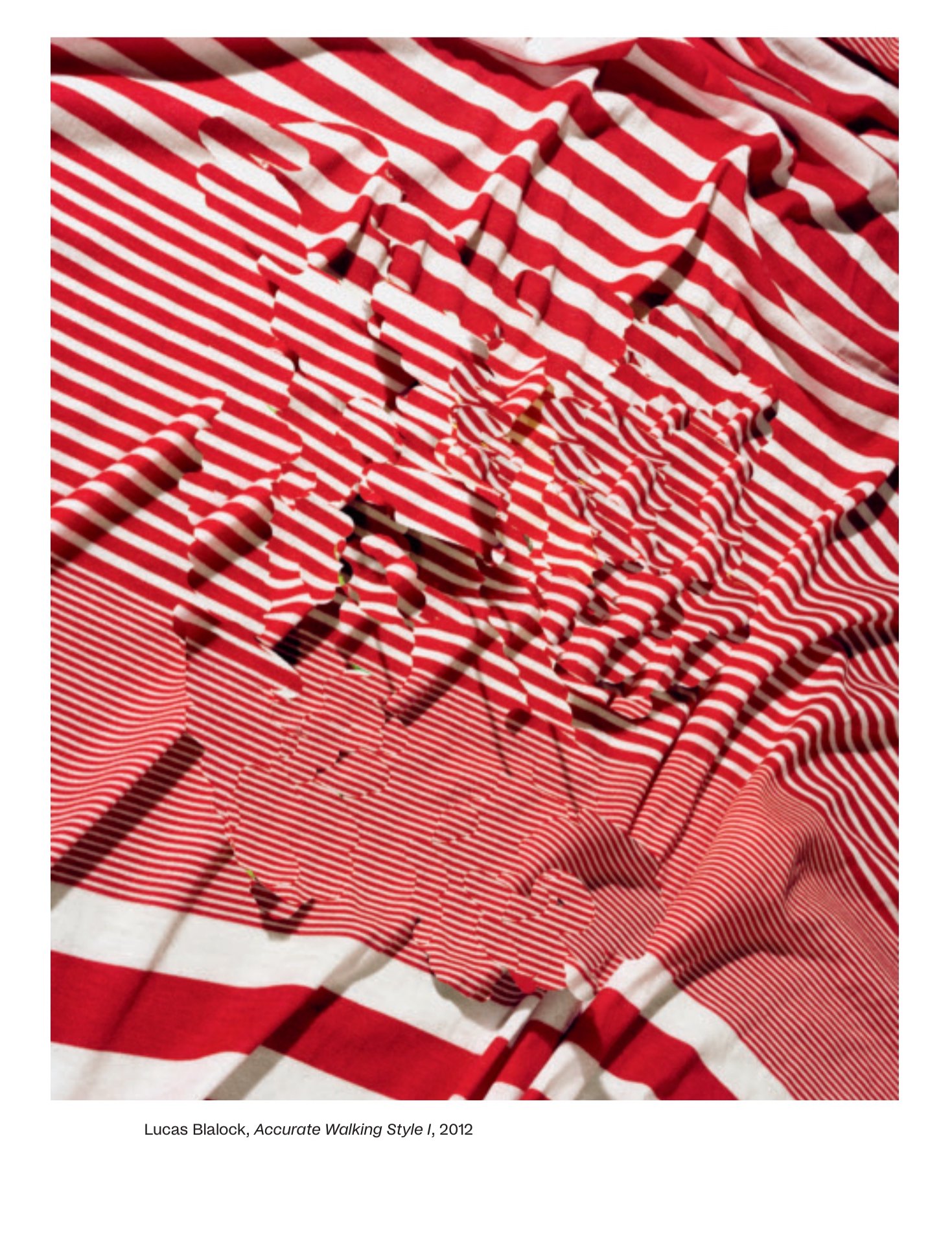

11. In my pictures, I’m always looking for language adequate to my own subjectivity, my own messed-up feelings, and this is something I hope viewers might be able to mirror for themselves. Photography is nothing like a verbal or written language in most respects, but, like language, it is in common use. We all ‘speak’ photography and this makes it a particularly interesting form in which to work. Like language, it changes as our use of it alters, shifting to accommodate new uses, evolving socially, and making space for importations and slang. There is a root system in both, but neither is essentially itself—it becomes by being used.

I've always been attracted to photography that poses a threat to itself. I probably work the way that I do – using so many found and collected images – because I’m distrustful of how seductive photography can be. But I can't really shake it either: I feel too tender towards the photographic object. I love feeling them, seeing them in relation to each other. I often describe myself as a photographer who doesn't make my own pictures for this reason. T

On the occasion of Paris Photo, Objektiv Press will present this summer’s project Double with Carmen Winant and Carol Newhouse at Les Rencontres d'Arles, featuring a presentation from Winant along with a conversation with her, Elle Pérez and Lucas Blalock over coffee and croissants.

Coffee & Croissants – Delpire & Co

Saturday, 15 November 2025, 11h

We will also hold our tenth pop-up event at Polycopies! This year, we will focus on the books from Winant, Pérez and Blalock,, but other titles will also be available..

The picture of Jose de Jesus took about a year to make. The image itself holds a reference to Señor de Papantla by Manuel Álvarez Bravo, one of my favorite artists. I had the luck of being able to study his prints when I wasteaching at the Williams College. As with the works of Peter Hujar and Roy DeCarava, so much happens in Bravo’s shadows.

When we could still afford to have a stable world view, an image could shift our perception of the world. In this sense, it’s the billion collective images that I’ve consumed in the past ten years that have resonated with me the most. Slowly, over time, the power of a single exhibition or image to change one’s perception has been put to question. In a time of relentless and almost involuntary consumption of images, the rise of mass-market digital retouching and live rendering software, can a single image hold power?

Santu Mofokeng’s photographs from the series Chasing Shadows and Black Photo Album/ Look At Me & Carrie Mae Weems’ images from Kitchen Table Series and Family Pictures are still on my mind. The influences and events that have changed the atmospheric pressure of my working space are oral histories, self-recollection and the recollection of others, autobiographical narratives, psychoanalytic theory and therapeutic practice dealing with transgenerational trauma.

As a student I was obsessed with Steiglitz’s photographs of Georgia O'Keeffe, how we could watch her age (becoming more handsome with every year). We saw what Steiglitz saw (although O’Keefe lived much longer after he died). What a privilege the photographer grants the viewer, a stranger to the world of her intimacy.

Shadows and forms seem to reach out of the frame and pass right through the installation space. A hand approaches or withdraws from a chest blemished by marks. The fragility of this skin that has just been touched or is about to be touched contrasts with the image itself, which manages to convey the opposite of fragility. The black and white photograph comes from another time and yet is so necessary in our time.

I’veI’ve been thinking about something that Eline Mugaas once told me: a film still that has stayed with her for a long time. The scene is from one of Constantin Brancusi’s films shot in his Paris studio. A woman is dancing on a low plinth, her body twisting as she raises her arm above her head. The movement reminded Mugaas of other images throughout art history, from antique caryatids – columns shaped like women's bodies whose function was to hold up temple roofs – to the Greek urns from the geometric period, stylised as women raising their arms above their heads and pulling their hair in grief.

Still thinking about Ingrid Eggen's pedknots. They look so uncomfortable that it actually hurts to watch. It seems as though toes have been amputated. This makes me think about how we continue to survive in our bodies. Eggen has consistently worked with the human form throughout her artistic career – previously using symbols and signs tied to communication, where she explored how physical expression can be distorted to create something new, based on the body’s unconscious ways of collecting and storing information.

My bag is heavy with books about other artists as I walk through the vast halls of the museum. I’m so impatient to find the Becker that I barely register Bourgeois’ Maman, which usually makes my breath catch. I only stop when I reach the large-scale black and white piece by Sophie Ristelhueber—scarred skin from her Every One series, inspired by her visit to war-torn Yugoslavia. The photographs were taken in a Paris hospital: fourteen close-up images of post-surgical scars serving as symbolic stand-ins for the wounds of conflict.

Double opens with a series of photographs of a woman practising Tai Chi on a beach, apparently alone, moving in and out of the waves. She seems lost in her own movements. The year is 1974, and the woman, along with her two friends, is weeks away from discovering the land where they will build a new community. They have left everything—their homes and families—to find a place where they can live outside society. This short photo-novel of the woman on the beach serves as a symbol of that dream.

In a 2022 conference, On Wimmin's Land at Oregon University, Carol Newhouse talks about her experience at WomanShare, about sharing her life through photography—how she spent time in the funky little darkroom they built, staring in wonder at her photographs. She wanted to capture the strength she felt on the land. She reflected on how to create images that conveyed a sense of togetherness in an environment that was both healing and challenging.

Is it possible to leave everything behind? Is it possible to begin again, outside and beyond every system of living you've ever known, reinventing what it means (and looks like) to exist as a body and soul on the land?’ These questions shaped Carmen Winant's exploration of radical reinvention, particularly within the context of the lesbian separatist communities of the 1970s. Through this process, Winant connected with Carol Newhouse, co-founder of Womanshare, a lesbian feminist community on the West Coast of the United States.

I like to compare it to walking—something very natural for us, just like the act of seeing. But then, once you stumble over something, your next steps become cautious. You think, “I have to be careful,” and you place your foot more deliberately. You become aware of something that usually happens automatically. And for me, Rødland’s images work the same way. They are images you stumble on, and suddenly you become aware of your own process of seeing—how you see, what you see, and how you move through the world. Afterwards, you’re more attentive to the imagery that surrounds you and the mechanisms behind it. At least, that’s the effect his images have on me.

So I try to reframe the picture—literally and metaphorically. I adjust the aperture. I redefine what accomplishment means. For me, it’s these bonds—this rhizomatic support system—that I return to. For a long time, I kept a rejection letter from a theatre school I desperately wanted to attend framed on my wall as motivation—a reminder that good and bad things are two sides of the same coin, and that neither should be clung to too tightly. But I’ve replaced it now. I chose this photo instead. It’s also a motivator—but one that celebrates the connections I’ve made, the ongoing and slow-moving process, not just the moments of success or failure.

In Moyo, Akinsete portrays a man, partly in shadow, sitting on the edge of a flowery sofa, looking solemnly out the window in front of him. You can’t tell whether he’s focused on something happening outside the window or if he’s not looking at all, just deeply embedded in his own mind. But you know that he sits alone in this room, looking out.

Jumana Manna’s twelve-minute-long film, A Sketch of Manners (Alfred Roch’s Last Masquerade), 2012), was first shown in Ramallah, at the A.M. Qattan Foundation’s Young Artist Award 2012, where Manna won first prize. Drawing vectors between photographic image, historical re-enactment and geopolitical space, the film is particularly interesting in the way in which it re-imagines history.

Founded in 2009, Objektiv began as a biannual journal dedicated to lens-based art. The very first issue was released in April 2010. After a decade of exploring that format, Objektiv transitioned into a more book-like publication, inviting a single writer to fill its pages with raw and authentic reflections on trends within the medium.

My favorite photograph of Atget’s is deceptively simple. It is from 1925, two years before his death. He made it during the seven-o’clock hour as winter turned to spring in the Parc de Sceaux. A tree cuts the frame vertically, splitting our view of the water in half. This formal choice creates the illusion that the pond is a waterfall—or a portal to another plane of existence.

It could be the image of the watermelon that lingers in my mind as I sit at Zürich Flughafen, waiting for a flight from a non-EU country back to my own. The reopening of Fotomuseum Winterthur has been reassuring—it’s a place where lens-based art is taken seriously. And this series on how we relate to emojis in our digital world feels important.

Although this body of work was made over two decades ago during the high phase of postmodernism, its concerns around the way that truth is constructed resonated deeply. Its critical engagement that is, with the photographic image as a composite of interwoven narratives and suspensions of disbelief, felt timely and urgent against the backdrop of a politics increasingly stranger than fiction.

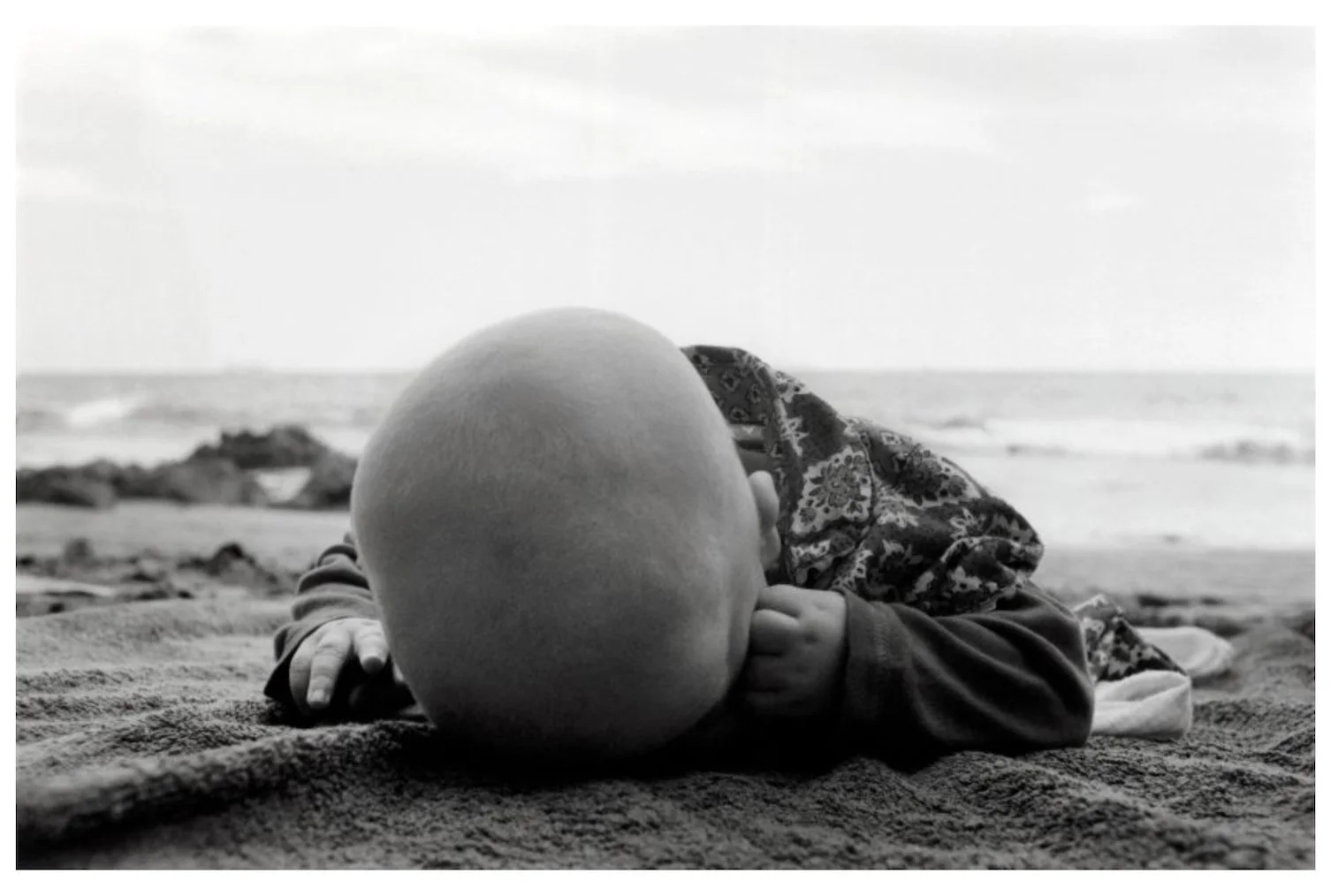

I find myself drawn to images that carry an ambiguity—a kind of visual dissonance. A story only half-told. Something has happened, and the image holds that space open. I think of Tom Sandberg’s photograph of a child with their head buried in the sand. That quiet tension, that sense of something just beyond reach.

There is an image of Simone de Beauvoir on my mind. It’s a composite photograph, created by blending images identified as her by facial recognition programs. The result is an AI-generated portrait: a machine’s interpretation of identity. It’s surreal, yet strangely vivid—a young version of de Beauvoir—but I remind myself that it is a photograph never actually taken, she never posed for this and yet it now exists in the world. Its subtitle, Even the Dead Are Not Safe, feels truer than ever.

From Objektiv’s very first issue in 2010, we’ve asked a wide range of people to describe the image they can’t get out of their minds. Afterimages is an ekphrastic series about that one image that lingers behind your eyes—the one that won’t let go. We invite artists and writers to reflect on an image they can’t shake. This column has been part of Objektiv since the beginning, originally titled Sinnbilde in Norwegian. As the sea of images continues to swell, the series asks: which visuals linger and take root in today’s endless stream? Much like a song that plays on repeat in your head, these images stick. Whether it’s a billboard glimpse, a newspaper portrait, a family photo, or an Instagram reel—we’re drawn to those fleeting moments that stay with us.

Later, I wrote a thesis using Roland Barthes’ idea of the punctum in an image, exploring how this was my first encounter with such a punctum. It became an image that is very dear to me; I’m still captivated by it many years later, and it continues to evoke strong emotions for me.

There is a seagull in Peter Hujar's exhibition Eyes Open in the Dark at Raven Row. It's Sunday noon, 23 March 2025—spring, with warm, damp air, soft and almost raining. Last night, my friends and I went to see The Seagull (Chekhov) at the Barbican in London, with Cate Blanchett in the lead role. Actually, there are no lead roles, it is directed by Thomas Ostermeier.